Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban, book of a lifetime: Mind-blowing audacity

Hoban's book is a work of such colossal and devastating invention it makes other novels look weedy by comparison

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Most writers like to imagine they're doing something a little different – in some modest way perhaps challenging the conventions of form or having their characters articulate some observation that hasn't been articulated before. Riddley Walker is a work of such colossal and devastating invention it makes other novels look weedy by comparison. As a reader you're inclined to laugh out loud at its mind-blowing audacity. As a writer you're tempted to turn off the computer and go back to bed.

It's a long time since I read it. Whoever recommended it warned me that it would take a dozen or so pages to get the hang of it and they were right. The story is told in the first person but phonetically, so you quickly work out that the best way of making sense of this fractured language is to say it aloud and, in time, to hear it spoken in your own head.

"Like Ive said it stayd qwyet all day we dint hear nothing nor there wernt no lerting from the dogs. A little too qwyet I thot it wer. Qwyet with may be eyes and ears in it waiting for us to make our move."

At first, the story – packed full of wild dogs, spears and superstition – combined with the way it's delivered, seems medieval. But the more that boy's voice chatters madly away inside your skull, the more you appreciate that this tale is set in the future – a future in which things have gone mightily wrong.

I'd be lying if I claimed to remember all the details. What I remember is a boy on a perilous journey through a sort of reconfigured, re-imagined Kent, doing his best to solve a riddle. But what made the book so memorable was that, as a reader, I was called upon to reassemble the text and try and solve the riddle, giving me the sense that I was in on the creation of the text itself.

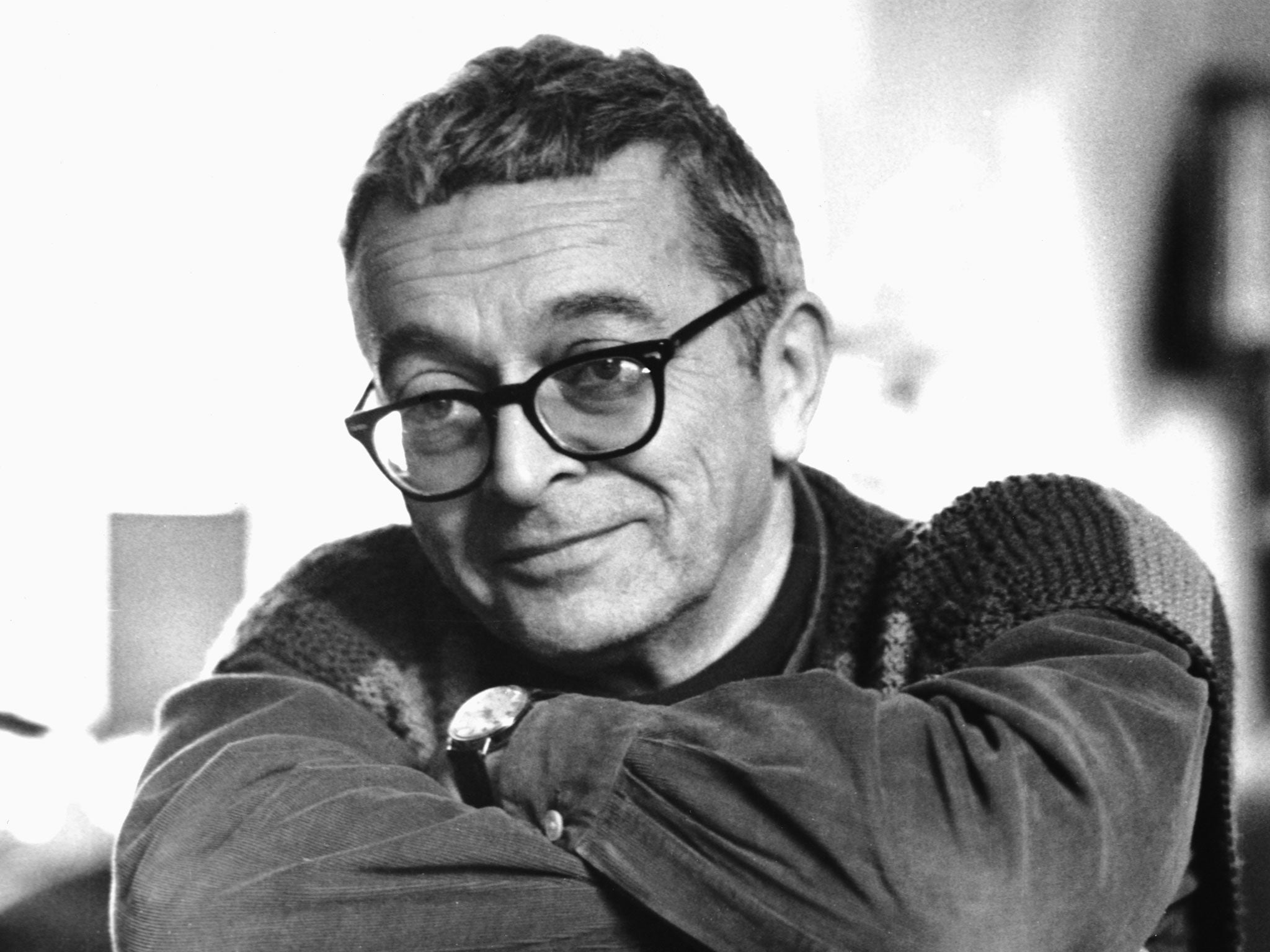

A year or so before his death I saw Russell Hoban discussing the book at a packed venue. I remember he talked about the composition of each of his novels as an unpredictable journey. Sometimes, he said, he'd end up in the Big Rock Candy Mountain; sometimes he'd wind up in the middle of a desert.

Towards the end of the evening a member of the audience asked Hoban why he thought Riddley Walker was so immensely popular. Hoban thought for a while. "Well," he said, "probably because it's such a bloody good book."

Amen to that.

Mick Jackson's new novel is 'Yuki Chan in Brontë Country' (Faber)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments