Review: Granta 123 - Best of Young British Novelists 4, Edited by John Freeman

These may well turn out to be the brightest writers of their generation, but while some work truly shines, the list fails to satisfy as a collection

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

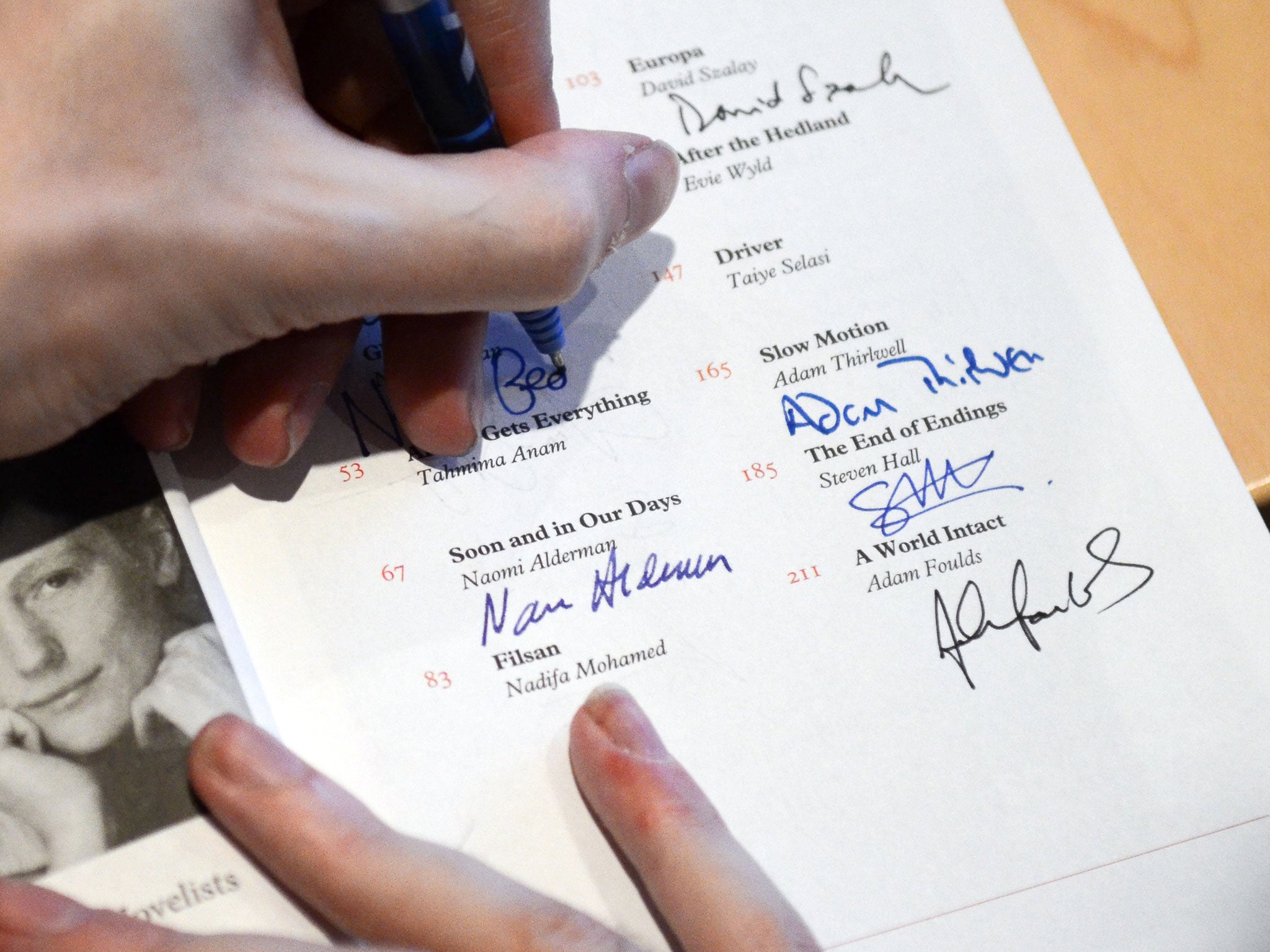

Your support makes all the difference.For the fourth time since 1983, Granta magazine has announced its list of the 20 "best young British novelists" with great fanfare. Having accurately predicted the success of fledgling authors such as Monica Ali, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Adam Thirlwell (and, to a lesser extent Philip Hensher and Jeanette Winterson, who were quite successful already) it is understandably looked to as a barometer or a marker of Where Literature Is At.

Some of these analyses are more worthwhile than others. For instance, it is interesting that so many of 2013's "best British novelists" are immigrants, writing about Britain from a recent arrival's perspective, or not writing about Britain at all. As John Freeman points out in his introduction, there are "three writers with African backgrounds, one who was born in China and only began recently to write in English … one from Pakistan, another from Bangladesh … one born in Canada of Hungarian descent …" and so on.

It is far less promising to push against the statistic that 12 of the 20 writers are women (up from eight in 2003) and try to see a sudden swing towards women's fiction being taken far more seriously than men's, which must surely lead to the imminent dismantling of women-only prizes. And yet some people have deduced this so-called trend from a number hovering just over or just under half.

Now that the dust has settled, what can we see in this literary crystal ball? Helpfully, this year's panel have introduced a new phase to the judging process. As well as studying the form of every writer under 40 with a British passport and a publishing deal, the judges asked authors to submit a new story or part of a new novel. Those stories and extracts appear here, which gives readers a small insight into what the judges considered. Unfortunately, it does not make for a very readable collection.

Of the 20 pieces of writing, only three are discrete stories: "Soon and In Our Days", by Naomi Alderman; "Driver", by Taiye Selasi; and "Submersion", by Ross Raisin. And they are fab.

Alderman is already the author of three acclaimed novels and a best-selling zombie-based fitness app, and the story that represents her here shows the deftness and humour that should guarantee her a long career. It begins: "On the first night of Passover, the Prophet Elijah came to the house of Mr and Mrs Rosenbaum in Finchley Lane, Hendon …"

"Submersion" is a dreamlike remembrance of a drowned village. It starts at a "beachside bar in a small resort", but it takes a sinister turn even as the narrator is airily dismissing warnings of carnage. "If it floods, it floods," he says, picturing "parsnips floating up to the surface as pale and bloated as babies' limbs".

"Driver" is a new story by Taiye Selasi, whose first novel Ghana Must Go was published last month and had already marked her out as a writer to watch. Its narrator is a young man working as a chauffeur for a rich Ghanaian family, and it skilfully sketches as many minuscule social dramas as a classic 19th-century English novel.

Male migrants who resignedly work at menial jobs are common to many of the stories. "Anwar Gets Everything" by Tahmima Anam – an extract from Shipbreaker, the last in a trilogy that started with A Golden Age and The Good Muslim – revolves around a Babel Tower of migrant workers toiling through the heat to build a giant skyscraper in the city of Dubai. David Szalay's "Europa" has three Hungarians on a dodgy mission to London. "Arrivals", by Sanjeev Sahota, is about immigration, struggle, and hierarchy, but also about what happens when a dozen young Indian men have to share a small kitchen.

Some of the excerpts from "forthcoming" novels make the reader wish that the novels were finished now. One such is "Vipers" by Kamila Shamsie, a sensual and tender exploration of the role played by Indian soldiers in the trenches of the First World War. It begins: "Qayyum raised the buttered bread to his nose, the scent of it a confirmation that Allah himself loved the French more than the Pashtun." This 18-page extract is too tantalising. Likewise, Helen Oyeyemi, Evie Wyld and Sarah Hall are always intriguing, and never more so than in these teasing snippets from novels to come.

Other writers are less well represented. I'm sure that Jenni Fagan's "novel in progress" will be marvellous, but the extract here is mystifying. Why is Cael drunk on a bus? What's he doing at a deserted caravan park? And is there really a woman outside sleep-vacuuming the road?

Granta's fourth attempt to highlight the best novelists of their generation may well turn out to be just as prescient as the first three. But this uncohesive collection does not work as an anthology, or serve as a guide for readers hoping to join in the futurology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments