Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

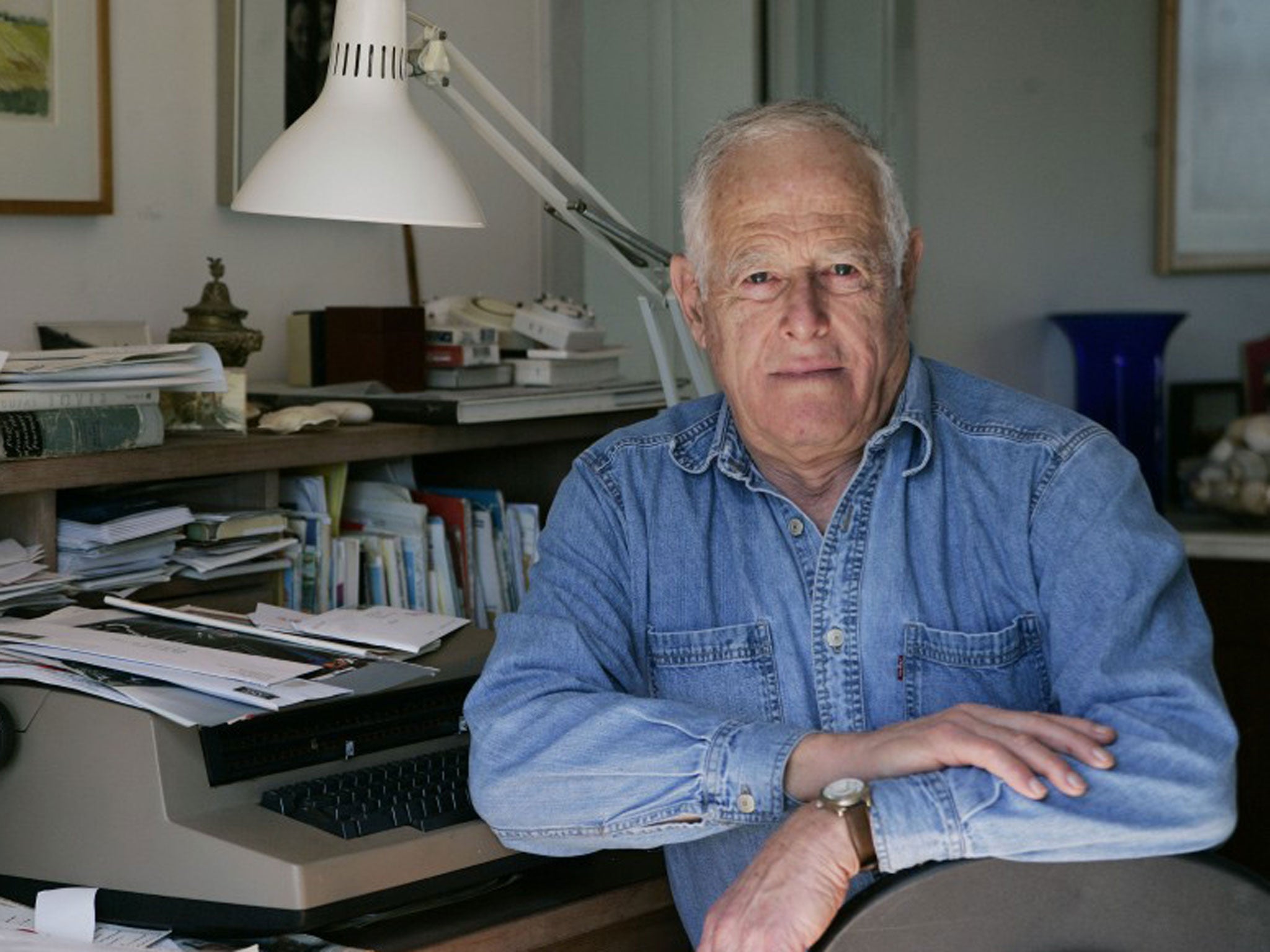

If some writers see their pens as a prism reflecting their thoughts on to the page then here, in James Salter's first novel for 35 years, a veil covers the glass. Part Bildungsroman, part elegy for death still to come, All That Is homogenises events and emotionally disconnects its central character, a World War Two veteran who enters a publishing career. The book's tempered language places the profound and commonplace side by side, affording tragedy the same impact as commuters in traffic; failed marriages are described with the regularity of meals.

Richard Ford, in the introduction to Salter's 1975 masterpiece Light Years, praises him for the quality of his sentences, the first three of which, from that novel, are worth reproducing here: "We dash the black river, its flats smooth as stone. Not a ship, not a dinghy, not one cry of white. The water lies broken, cracked from the wind." Since then, such extended rhythms, employing repetition, have become less pronounced. This heightens what Ford describes as a mode of "decrying" against the trivialisation of life and sentimentality. The banal, the incidental, the clichéd, are all included in emphasised realism, not always enjoyable, but often true.

The most arresting writing in All That Is, apart from two key scenes, comes at its beginning and end. Our journey with the central character Philip Bowman begins in the US Pacific war against Japan, where "men were slaughtered in enemy fire dense as bees, the horror of the beaches, swollen bodies lolling in the surf, the nation's sons, some of them beautiful". This lyrical combination of the historical and specific is captivating and atypical, if less artistically interesting than the rest of the novel's attempts to mine the everyday. This interest applies both to the reader and to Bowman himself. Later in the book, he is asked: "What has your life been like? ... What are the things that have mattered?". He replies: "The navy and the war." Though of even this he is unsure.

Otherwise his existence – and the narrative with it – extends to the New York and London publishing scenes, Bowman's extensive social circle, his predatory libido and failed relationships. Description functions like an accordion, in which pages can concertina to decades or minutes as the plot demands. There is a tendency to flip between characters of varying relevance. Digressions include the early sexual life of Francis Bacon, whose "eloquence came from his father's coldness and disapproval and the great freedom of finding his own life in Berlin with its vices, and Paris, of course". One man's failure with women causes his suicide, afforded barely more prominence than a presidential assassination. The book's coda is similarly cursory, repeating the belief of Bowman's mother that one's fate beyond death is whatever one wishes for, before the quotidian, inevitably, rises up.

These bookends aside, if anything exemplifies this character's existence – apart from sex – it is the heightened nature of what is usually considered commonplace. To this end, Salter tears up the creative writing rulebook in his dialogue, comparably atonal to Light Years. Platitudes and exposition abound. The writer's economy does not extend to wiping out greetings or conversational asides, for example, which are always relayed neutrally, allowing readers to impose their own interpretation on whatever the speaker may be feeling. There is one scene in which Bowman interrupts a woman's discussion of a relationship to remark on a mouse scuttling across a room. Such confidence feels unique, almost ostentatious. This novel has fewer than 300 pages.

Sadly, it is what Ford called Salter's position in the "writing-about-sex hall of fame" that provides some clunky passages. No amount of character naivety can excuse the sentence: "She was lively and wanted to talk, like a wind-up doll, a little doll that also did sex." Or, "he imagined her a few years older with certain unfatherly thoughts though he was not her father". The seriousness of "he came like a drinking horse", an already notorious line, is questionable. The obsessive coveting and propositioning of other men's wives is relevant in Flaubert but is too prominent here.

The emotional pummelling of All That Is, then, may begin with the capsizing of the Japanese battleship Yamato in 1945 but maintains its sustained assault through a life painted as emotionally grey. If anything Bowman's world is enslaved to the pursuit of women – more honest than Updike or Roth, and also more saddening, somehow – that enables its creator to define the terms of his own immortality. It would be discourteous to suggest that this is this author's final work. As a confirmation of his long-recognised contribution, of his own wish to preserve in text what has "any possibility of being real," as opposed to a dream, as stated in the novel's epigraph, it is both needless and rewards him with the existence beyond death that he so obviously deserves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments