Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Dave Eggers' new novel hits you with prose as stark and as luminous as its Saudi Arabian setting. A Hologram For the King tells of Alan Clay, who travels to King Abdullah Economic City to sell an IT system. As he waits to deliver his pitch, Alan encounters Saudis and expats in scenarios which make him look at himself and wonder: "Who was this man?"

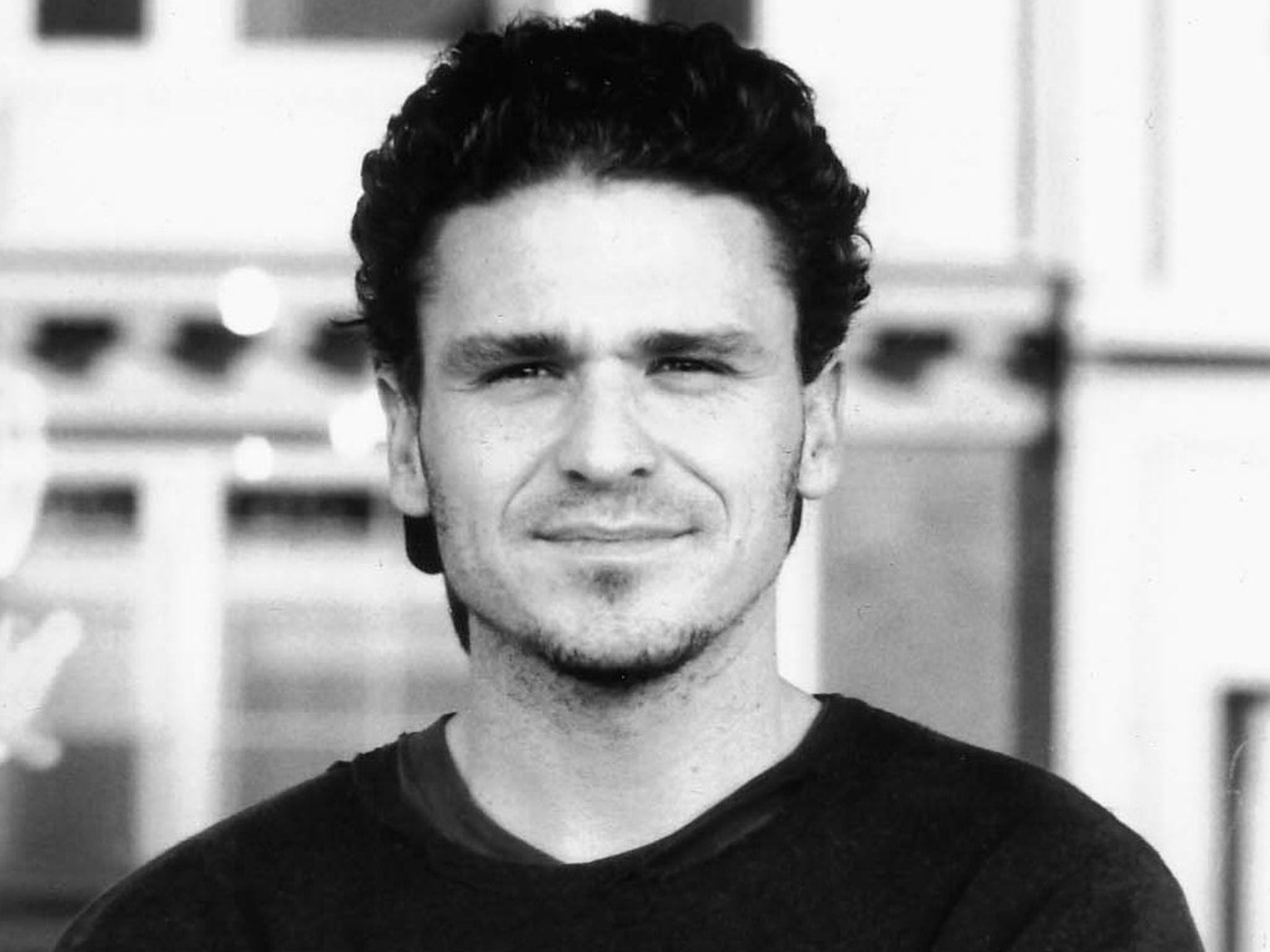

Readers might ask similar questions about Eggers. Since his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, he's enjoyed success as a publisher and magazine editor, and founded literacy initiatives for children. His last book, 2009's Zeitoun, a non-fiction account of a Muslim man's traumatic experiences in hurricane-ravaged New Orleans, demonstrated Eggers' gift for telling real people's stories in unobtrusive prose. A sense that he's never quite marked distinctive literary territory persists, but while his seventh book exhibits his versatility again, it should confirm Eggers' position among America's leading contemporary writers.

It comes to us in an attractive hardback edition which would delight its former manufacturing executive protagonist Alan, who – like both the country he hails from and the country he visits – is full of contradictions. He laments the overseas outsourcing of American manufacturing even though, in his managerial heyday, he opened factories in communist Hungary and busted union power in Chicago. "We don't have unions here," explains Alan's young Saudi guide, Yousef. "We have Filipinos." Alan's alertness to the Kingdom's hypocrisy fluctuates: he's curious about veiled women and jump-suited labourers, but when he's allowed to "pilot a gleaming white yacht through the pristine canals", he fantasises about buying a second home. Alan can't afford one of KAEC's pink condos, however, because he's struggling to raise his daughter's college fees, owes thousands to investors, and feels "superfluous to the forward progress of the world".

He's desperate to sell his hologram technology but weeks drift by with no sign of King Abdullah. One night, drunk on an illegal liquor named "siddiqi", Alan takes a steak knife to a cyst on his neck. Prohibition means Western visitors are "forced into the role of teenagers hiding their vices and proclivities from a shadowy army of parents". At an embassy party, Alan discovers a bacchanalian "bootlegger's paradise". He witnesses the more profound consequences of such strict laws when he meets a young musician who surreptitiously plays guitar. Saudi offers little to educated subjects like Zahra, a middle-aged doctor who snorkels topless so that observers might mistake her for a man.

Alan is convinced that his experiences pale by comparison to his Irish ancestors' arrival in the US and his macho father's heroics in the Second World War. The King's embryonic city appeals to Alan's longing to be present "at the beginning of something", to enact part of the pioneering that's enshrined in American mythology. But his inconsistencies limit the reader's sympathy: Alan is incapable of imagining any alternative socio-economic system to the one that's ruining him, and he lacks interests. Boredom is "at once exasperating and alluring", so why doesn't he read a book? Does Eggers believe that to have his character do so would be unrealistic?

Beneath Alan's unimaginativeness, one senses the author's self-conscious compulsion to remind his readers of their minority status, to honour a reality, at once grinding and abstract, that prevails beyond the page. This patriotic novel confronts America's industrial decline, but its pertinence also threatens to prevent it from becoming more than a symptom of the stagnancy that it describes.

Alan's yearning for action and approval lead him into recklessness which jeopardises his burgeoning friendship with Yousef. There's potential for a fulfilling relationship with Zahra, whose affection for Alan borders on inexplicable, but, although he kisses her while they're swimming underwater, he rejects her later. This might be rooted in a despicable line that he quotes from his ex-wife: "I don't want to have sex that someone wouldn't watch."

Perhaps he shares her lack of self-respect, but his ex's words echo Alan's response to news of the 2010 Gulf Coast oil leak: "Just end it, please. Everyone's watching." Even the most personal anxieties of the man who's pedalling an illusion are reflected in the wider world. Alan disappoints friends, hurts women and is a lousy businessman, but to his daughter he remains whole. "I'm the eye in the sky … I can see where you started and where you're going and it looks perfectly fine from up here," he writes to her. His siddiqi-soaked letters might be implausibly eloquent but they show a wise, sensitive parent.

It's fitting that a novel which eschews easy solutions borrows its epigraph from Samuel Beckett: "It is not every day that we are needed." Beckett, like Alan, knew about waiting for somebody who might never arrive. Unlike Eggers and his protagonist, he was uninitiated in the consolations of fatherhood.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments