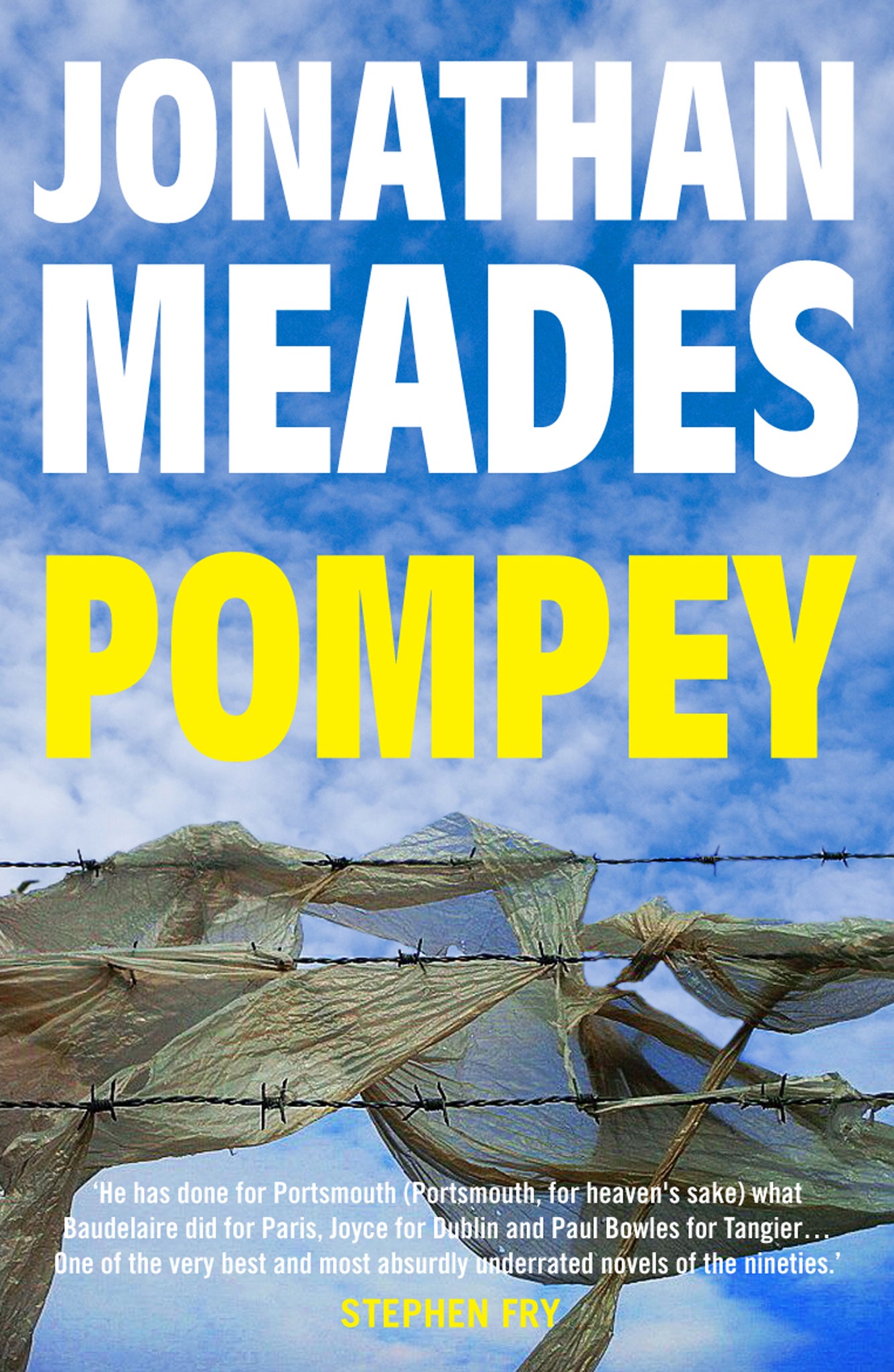

Pompey by Jonathan Meades: Book review - a startlingly filthy read that shows Meades on top form

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jonathan Meades has a talent for ordure. Where his first collection of stories, Filthy English, achieved the distinction of covering in aggressively vivid prose the disciplines of murder, addiction, incest and bestial pornography, Pompey exhibits an even greater concentration of his aptitude for squalor.

Enemas, sexual abuse, quasi-necrophilia, sodomy, bestiality (again), incest (again) – all make an appearance, and by the end of the opening two pages, which must rank among the most startling affirmations of omniscience in 20th-century literature, the reader has met with an arresting injunction: "After using this book please wash your hands. Thank you."

Pompey tells the story of the four children of Guy Vallender, a firework-maker. Each child has a different mother, each leads a life that intersects with that of the narrator ("I know more than anyone about the firework-maker's children"), and not one is possessed of characteristics that might be described as normal.

The beautiful Bonnie is destined for a life as a junkie porn star; Poor Eddie is a geeky weakling with a propensity for healing; "Mad Bantu" lives with an affliction that was visited on him in utero (his prostitute mother bungled an abortion); Jean-Marie is a gerontophiliac. Over the course of the novel, a long family saga, Meades offers an unsettlingly intimate vision of this collection of anomalies, of "their antic lives and special deaths".

It is a stunning performance, and places Meades in the upper echelon of 20th-century prose stylists. His use of language is relentlessly inventive, violent, fresh, precise. He shares with the great stylists – Dickens, Joyce, Nabokov, Bellow – the ability to make the world appear alien while rendering it a more intense version of itself, and the power to recalibrate the reader's own perception of the environment in which they live.

Pompey will not please everybody. Nor should it. If you are the kind of reader who wants to "identify with" or "like" the characters in fiction, do not read this book. This is a novel from a writer who understands that literature is concerned with the inverse praise of good things, who is able to be moral without ever being moralising or moralistic, and who has dispensed with the polite fictions that we peddle in order to hide from ourselves.

For that reason, and for many others, Pompey will endure. You are welcome to wash your hands when you have finished this book. You will find it harder to remove the stains from your mind.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments