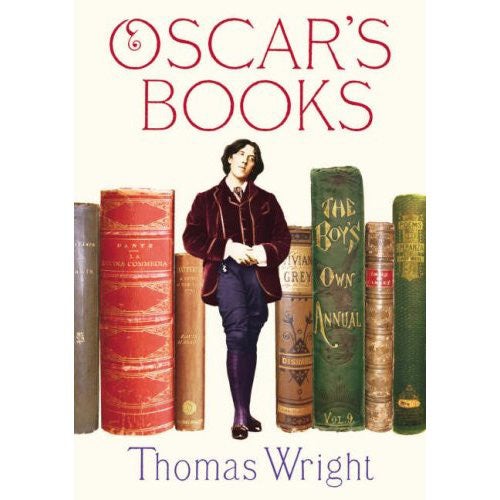

Oscar's Books, By Thomas Wright

A picture of Oscar Wilde through the literary works that were his reality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This arresting book on Oscar Wilde as reader has much to commend it, even if, finally, its ambitions are not quite achieved. Thomas Wright aims at an "entirely new kind of literary biography": an author's life told "exclusively through the books that he had read". His subject was not only an avid reader, but one who professed to find in books something more real than reality. Wilde was, moreover, a serial plagiarist. His own works unashamedly bore the traces of his voracious consumption of literary predecessors.

Wilde may seem an ideal candidate for the "inner life" Wright envisages. What wrong-foots the project is the "pull" not of the tales the Irishman read, but of Wilde's inventive, improvised life story. The tragic push of his bewitchment by Alfred Douglas; his entrapment by Douglas's father; the senseless force of British law: all altered forever the careful relationship Wilde had constructed in which literature outflanked life. Heartbroken, after his arrest, that his library had been sold to pay creditors, Wilde mourned a way of living and thinking he knew to have expired.

Prescience in his own writings has made people suggest that Wilde cast Douglas to live out the excesses of his fictional creation, Dorian Gray. Gray, likewise of unfathomable beauty, first destroys the life of an artist, then surrenders his own. Wright reminds us that, on being presented with an inscribed copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray by its author in 1891, Douglas read it 14 times.

But the awful denouement Wilde experienced resembled nothing so conscious. Rather, as Wilde the classical scholar understood, he became a captive in the unfolding of a Greek tragic nemesis. In Reading Gaol, he made sense of the pitiless surroundings by referring to Dante's Inferno. Scholars have much to thank Wright for, in tracking down so many extant copies of Wilde's library, and conveying much of his scribbled marginalia. The chief progenitors all feature: from Aristotle to Huysmans, Plato to Flaubert, Aeschylus to Pater. The Irishman famously cautioned André Gide "never to write 'I' anymore. In art, don't you see, there is no first person".

Richard Canning's 'Brief Lives: Oscar Wilde' is published by Hesperus Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments