My Song: a Memoir, By Harry Belafonte with Michael Shnayerson

Moving from poverty to super-stardom, the performer used his fame to support Martin Luther King and his cause.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

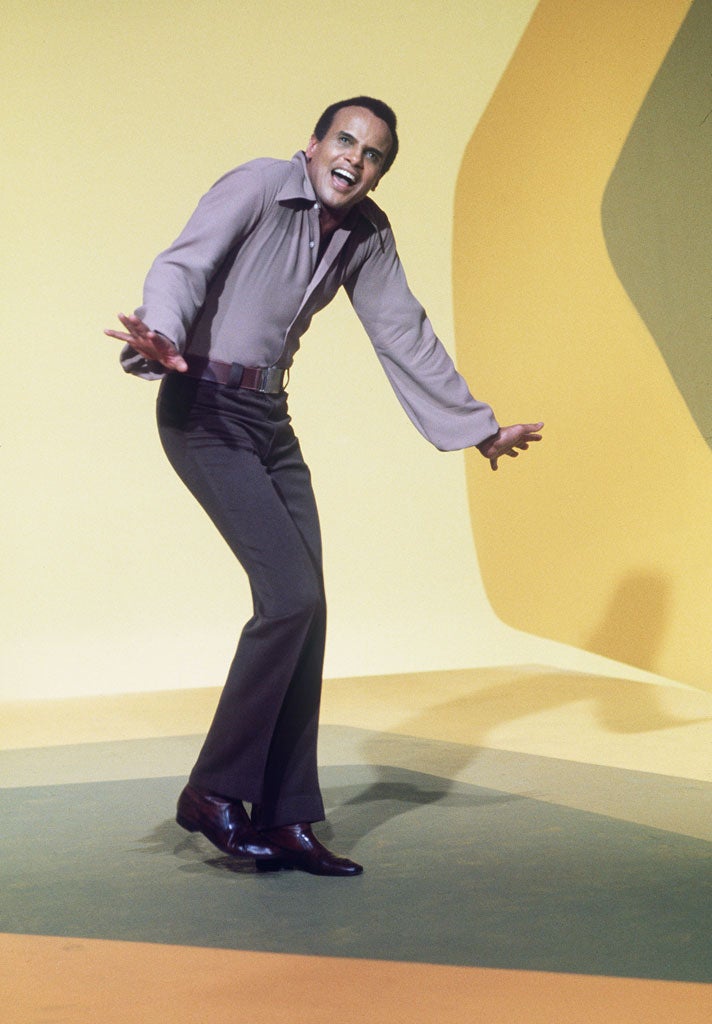

Your support makes all the difference.Few who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s are unable to sing a chorus of "Island in the Sun", "Scarlet Ribbons" or "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)", all hits for Harry Belafonte. His coffee-coloured good looks and honey-toned voice made him a star on stage, screen and vinyl.

Born in New York into poverty two years before the Great Crash, to a Jamaican mother with "a genius for survival" and a ne'er-do-well father, he began singing in Greenwich Village clubs while a student at the New School, where he had blown his GI Bill dollars on a drama course. Carmen Jones (1954), Otto Preminger's Hollywood reworking of Bizet's opera, made him a star and soon he was earning big bucks in Vegas – while suffering the indignities meted out to all blacks.

Unlike other black artists, he wasn't prepared to compromise. Long before they first met in 1946, Belafonte's mentor was Paul Robeson, the singer, actor and activist whose career, and health, were cruelly broken by Senator McCarthy. So when he answered his phone in spring 1956 to hear "a courtly southern voice" requesting a meeting at Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church, he had little hesitation in agreeing.

The 26-year-old Dr Martin Luther King had made headlines with the Montgomery bus boycott. Belafonte was admiring yet sceptical: other black preachers had abandoned Robeson et al in their hour of need. But King was "the real deal, a leader both inspired and daunted by the burden he'd taken on". When he asked for help, Belafonte didn't hesitate.

So began a friendship which involved the singer giving time, energy and a great deal of money to the cause. In August 1964, the terrifying "freedom summer" portrayed in Mississippi Burning, he flew to Greenwood, Mississippi, with $70,000 in a briefcase to support endangered students working on voter registration drives. Klansmen greeted his arrival. It was Belafonte who delivered singers and actors to the 1963 March on Washington, and to Selma and Montgomery, flashpoints of the civil rights struggle, and Belafonte who paid for the Kings' housekeeper.

Courted by both John and Robert Kennedy before and after the 1960 election, he was the go-between in their often cynical dealings with King. Belafonte, a keen gambler, played his hand skilfully.

His Upper West Side apartment was a both a refuge for King and a base where he could brainstorm. Belafonte and his wife joined Coretta Scott King at the open casket ahead of King's lying in state: the mortician's putty was all-too-visible in the head wound, and Mrs B "took out her powder puff, and dabbed gently at the discoloration until she got the tone just right".

This is an extraordinary story of a brave man who answered the call, is still answering calls. Yet he also put Nana Mouskouri and Miriam Makeba in front of American audiences, gave a young Bob Dylan his first studio session, blowing harmonica on "The Midnight Special", and even dreamed up the idea for "We are the World".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments