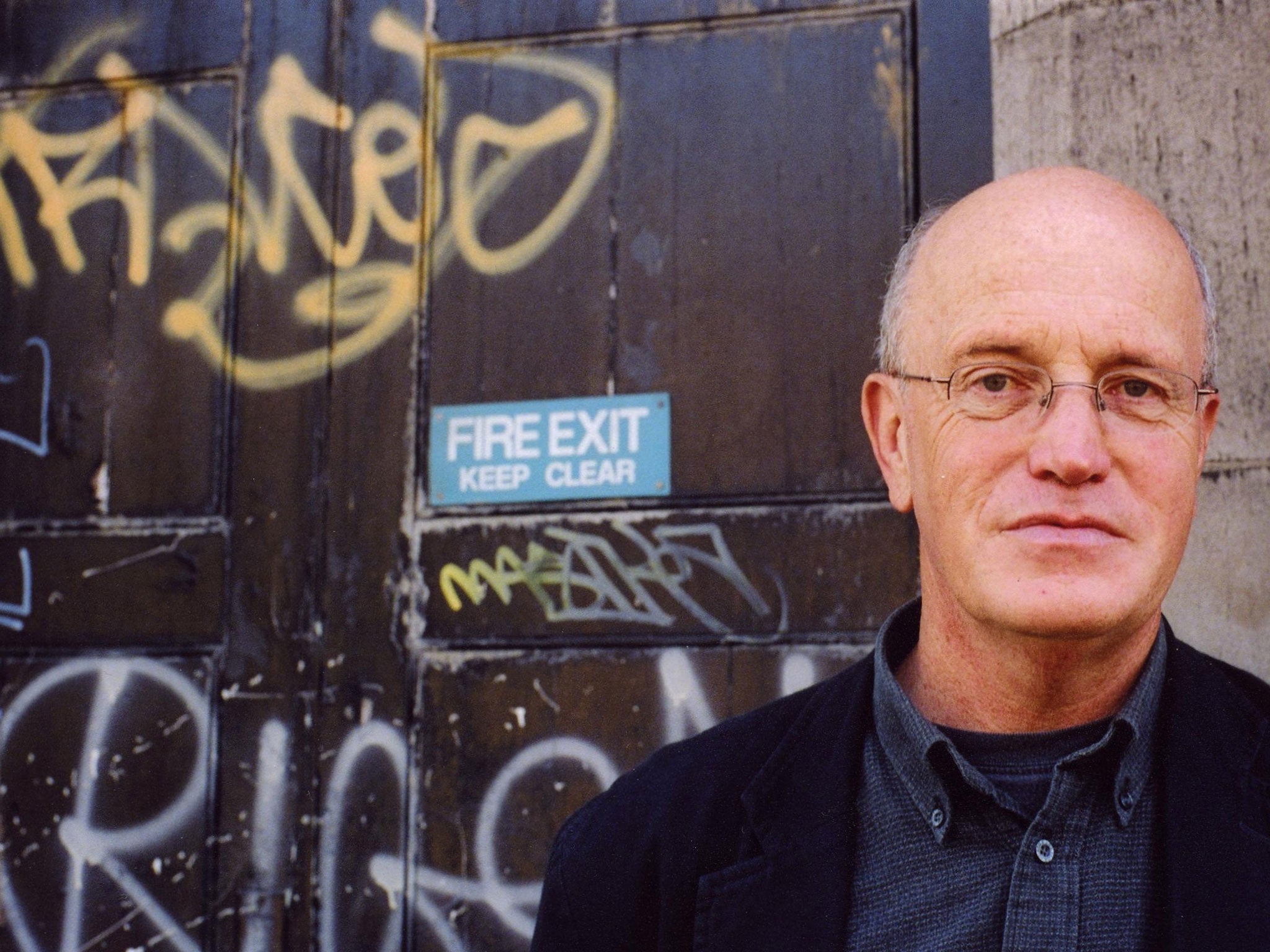

London Overground: A Day's Walk Around The Ginger Line by Iain Sinclair, book review

Fans will enjoy Iain Sinclair's jaundiced journey around the capital of cool quart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A signature stunt of Boris Johnson, who crops up here at Old Street with his "combination of innocence and feral cunning", the London Overground saw the last link in its broken Victorian chain welded back together in December 2012. In truth, as Iain Sinclair writes, this was "a very old railway revamped". Its ginger-coded circuit now serves the rebooted, hipsterised and gentrified inner suburbs along the route from Shoreditch to Peckham, from Wandsworth to Willesden.

Sinclair, that peerless London literary wanderer and street-level cultural archaeologist, decided that a trek around this ragged oval trajectory would do nicely as "the right walk for our present doleful period". Ask when Sinclair would have found his beloved, benighted metropolis anything but "doleful", and you might have to go back a fair bit. Possibly at the height of the Peasants' Revolt in June 1381?

Playing Sancho Panza to his Don Quixote was the maverick film-maker Andrew Kötting. Fortified by multi-ethnic nourishment from pit-stop cafés, they trudge around the Ginger Line within a single day – although he bulks out this foot-shredding marathon with repeat visits. Sinclair habitués, fans of dystopian voyages such as London Orbital (about the wider circle of the M25), Ghost Milk and Lights out for the Territory, will settle in for another jaundiced, visionary sift through "the beachcomber detritus of vanished worlds".

Shorter than those promenades, this book should also tempt newcomers on to Sinclair's terrain: that delirious, often hilarious urban palimpsest where pin-sharp observation, cultural hauntings and offbeat memoir fuse in sentences that catch your breath like a lurid toxic sunset over Hackney Marshes.

Here's one, chosen more or less at random: "Road and railway and woodland merged as we came, in clammy early-evening darkness, burned at the edges by mean spill from light poles and urgent beams from cars, like a necklace of flaring and furtive cigarettes, along the sudden, mind-stretching width of Wormwood Scrubs."

Thanks to the antic spirit of Kötting, his partner in grime, Sinclair's melancholia takes in plenty of merriment along the way. "Too much the aesthete of blight", he knows his literary temperament ("This old-man sourness is addictive") and games it into a sort of running, or rather striding, joke. Of course, he snipes at the resurrected railway's "fake pearls on a ginger string".

But Sinclair the prophetic scourge of London's hype-addicted developers has always had a gift for celebration too. Here, his circular journey takes in a pantheon of writers and artists he reveres: Angela Carter in Clapham; JG Ballard at Chelsea's phoney Millennium Harbour; the painter Leon Kossoff ("the railway was his muse") at Willesden Junction, the poet Allen Fisher in Brixton, part of a cherished "network of anarchic cut-up urbanists".

Older ghosts flit across the duo's path, from Apollinaire and Blake to Rimbaud and Freud. For Sinclair, they fill every London street with impacted strata of meaning and memory. If the Overground route forms "a battleground between antiquarians, lovers of the fabric of place, and thrusting futurists", then Sinclair helps to ensure that the "pragmatists, schemers, improvers, grabbers" will not prevail.

"A book is a city," he proclaims, typically winding VS Pritchett, Arthur Morrison and Thomas de Quincey into a grubby skein of Wapping tales. And a city is a book that, for as long as Sinclair writes, no bulldozer will ever close.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments