Literary memoirs round-up: Stories of grief with a happy ending

Alice Jolly’s Dead Babies and Seaside Towns to Alison Pick's Between Gods

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Misery memoirs. All the rage, aren’t they?” asks someone in Alice Jolly’s Dead Babies and Seaside Towns (Unbound, £14.99). “Yes,” Jolly replies. “But nobody is interested in a talking wound. Even a misery memoir has a happy ending. That’s the whole point of them.” There’s plenty of despair and heartbreak in these three memoirs, but true to form, each of the authors skilfully demonstrates what it is to transform even the most terrible of tragedies into something that manages to stand testament to what’s been lost, but ultimately looks forward.

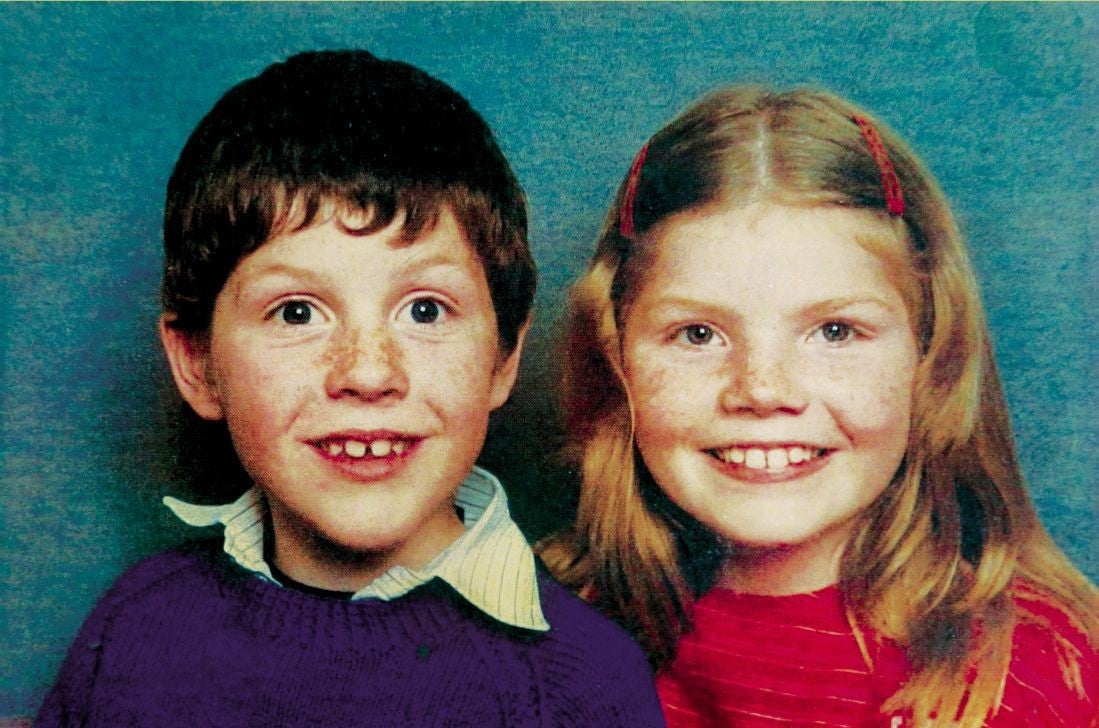

Two weeks before his GCSE results, Cathy Rentzenbrink’s 16-year-old brother Matty is knocked down by a car. Cathy, then 17, sits by his hospital bed wishing for nothing more than for him to survive, but little do she and her parents know that there are fates worse than death; and that the subsequent eight years Matty spends in a permanent vegetative state, before they apply for a court order to end his life, will turn out to be just that. Reading The Last Act of Love (Picador, £14.99), Rentzenbrink’s searingly honest account of how she struggled through life with this heavy “millstone” weighing her down, I was reminded of both Marion Coutts’s memoir of her husband Tom Lubbock’s death from brain cancer The Iceberg, and Akhil Sharma’s novel Family Life, the fictionalised account of the author’s own experience of how he and his parents attempted to cope in the aftermath of a terrible accident that left his brother seriously brain damaged. The Last Act of Love lacks something of the linguistic and literary alchemy of either Coutts or Sharma’s works, but it’s no mean achievement to turn such a “toxic narrative” into a book in which love and hope shine through.

Jolly’s memoir, by comparison, centres on the loss of a child, beginning with the traumatic stillbirth of her daughter Laura, an ordeal then followed by five miscarriages and a stalled attempt at adoption. Held hostage by this insatiable but completely illogical desire to have a second child (a conflict she’s fully aware of and wrestles with at length), Jolly and her husband eventually turn to surrogacy as their final option, offering a no-holds-barred glimpse into this secretive and seemingly often misrepresented world.

Despite not necessarily being a story that everyone can relate to – the experience is hugely expensive, and Jolly acknowledges how privileged they were to be able to afford it – her account is astonishingly moving and her prose nothing short of hypnotic.

“It’s important to tell your own story,” Jolly explains as she draws her own to a close, “otherwise someone else will tell it for you and they will almost certainly get it wrong.”

Alison Pick was brought up being told the wrong story about her origins. Raised in a loving home in Canada, it wasn’t until she was a teenager that she discovered her father’s family were Jewish, and while his parents had managed to escape Czechoslovakia during the Second World War – thereafter abandoning their religion for the apparent safety of Catholicism – the majority of the family died in concentration camps. Set while Pick was writing Far To Go, her Man Booker Prize long-listed novel inspired by her grandparents’ experiences, Between Gods (Tinder, £13.99), charts her conversion to Judaism. It’s a fascinating story about the ties that bind, even those one isn’t conscious of.

“Narrative begs an ending,” she writes towards the end of her book. “The desire to wrap up loose ends, to make meaning, is human, and ancient. But things do not end. There is only progression, shape-shifting, the flow of a current that crashes and tumbles, diminishes, almost dries up, only to give birth to itself again a little farther downstream.”

It’s a quote that fittingly describes the situation she, Jolly and Rentzenbrink find themselves in. “Grief is a disastrous subject for a book,” says Jolly. “It is slippery, episodic, repetitive. It lacks shape, or landmarks, clearly defined paths.”

She’s not wrong, and in less dexterous hands, these stories would be shapeless and baggy, confused and elusive, but instead each of these writers achieves the remarkable, and each memoir stands as its own act of love for those lost.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments