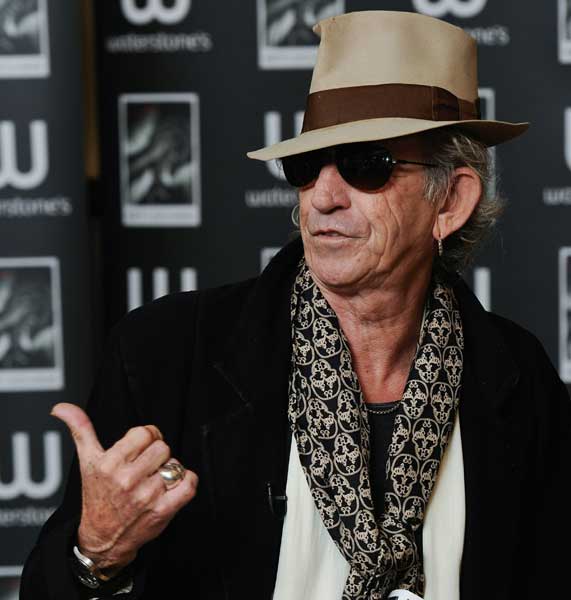

Life, By Keith Richards with James Fox

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Afterlife" might have been the working title for Keith Richards' autobiography, given the regularity with which commentators have predicted his demise. As early as 1973, when he was only 30, New Musical Express drew up a list of the top ten rock stars most likely to snuff it. Keith was at the top. "That was the only chart on which I was Number One for 10 years in a row," he writes ruefully. "I was kind of proud of that position. I was really disappointed when I went down [to number 9.] Oh my God, it's over."

Of course, it wasn't over. His cheery refusal to die of cirrhosis, lung cancer, cardiac arrest, from drug abuse, gunplay, knife fights, police harassment, nights behind bars and feral girlfriends has been accompanied by undying adulation. The British public loves an old scallywag.

But could he write a book? Recently there's been a foggy detachment about Richards, an air of puzzlement at the maelstrom of excess that whirled around his ankles for seven decades. Remember the old voluptuary on The Fast Show who ended every anecdote with the words, "Of course, I was vair' vair' drunk..."? Would the blues vampire turn out to be as blearily forgetful about his heyday?

The answer is a heartening No. The 500-plus pages of Life throb with energy, pulsate with rhythm and reverberate with good stories. It's a chronicle that takes the only-child Keith, with his shifty eyes and sticky-out ears, from wartime Dartford to the furthest shores of stardom, as the living essence of rock 'n' roll, the walking spliff, the human riff.

He tells it with complete, reckless, disclosure. Sometimes it sounds like a man ranting into a tape machine; sometimes, in the tidier and more reflective sections, you can detect the hand of his co-writer, James (White Mischief) Fox. But the watchwords of this book are honesty, confessionalism, telling it straight.

Richards savagely evokes his home town: "Everything unwanted by anyone else had been dumped in Dartford... isolation and smallpox hospitals, leper colonies, gunpowder factories, lunatic asylums – a nice mixture." He and Charlie Watts grew up in the council prefabs, all asbestos and tin roofs, provided by the postwar Labour government. Richards hated school, NHS dentists and bullies. He writes with feeling about his parents – his father worked as a foreman for General Electric, his mother demonstrated washing machines – and his charismatic grandfather, Theodore Augustus "Gus" Depree. This former dance-band leader, ladies' man and bohemian did mysterious things in the backrooms of shops and taught Keith, at nine, the chords of D, G and E.

It's piquant to discover that Keith's favourite-ever gig was singing in front of the Queen at Westminster Abbey when a choirboy aged 12; and to learn that, when his voice broke, he and his best friends were forced to repeat a school year. It made him a rebel. "I had a mad burning desire for revenge," he writes. "I spent the next three years trying to fuck them up." Can it be that the whole counter-culture bonfire, the whole Sixties spirit of rebellion, was sparked by a tactless choirmaster called Jake Clare?

Expelled, Richards fetched up at Sidcup Art College, thence to London and the Bricklayers Arms. There he formed the Rolling Stones around Ian Stewart, the piano player whose enormous chin debarred him from rock stardom; to sharing a seedy house in Chelsea with Mick Jagger and Brian Jones, watching audiences go crazy at the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, and being signed up to Decca records by the public-school wideboy and image-manipulator, Andrew Loog Oldham. It was, as he records, "fame in six weeks", and fame of an unprecedented kind.

The Stones's first tour in autumn 1963, supporting the Everly Brothers, Bo Diddley and Little Richard, saw outbreaks of teenybopper hysteria. Richards was alarmed by the casualty rate: "The limp and fainted bodies going by us after the first ten minutes of playing, that happened every night. Sometimes they'd stack them, up on the side of the stage because they were so many of them. It was like the Western front."

This is not the book's only wartime allusion. They turn up everywhere. Behind the Sixties rebel there evidently lurks a frustrated militiaman. Richards loved running the Beaver Patrol of the Seventh Dartford Scouts, festooned with stripes and badges. He writes about the discipline of keeping a band together. Playing in clubs is all very well, but cutting a studio record means you're "a commissioned officer, rather than one of the ranks." Absolutely, brigadier.

A passion for blues saved him from imploding when young. He explains, with rapturous delight, his devotion to Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter and Buddy Guy, and his annoyance at the kind of blues purists who booed Muddy Waters for playing electric guitar. You start to see how his meeting with Mick Jagger at Dartford Station in 1961, when both 18-year-olds were holding Chuck Berry albums, could have been such a life-changing moment.

Later he brings the same magisterial enthusiasm to explaining the process of songwriting or the power of the open-tuned, five-string guitar. In both cases he sounds quite unconcerned with seeming cool. His mini-essays fizz and sparkle with creative delight.

Some of the stories are over-familiar – the drug bust at Redlands, his Sussex country house, the ménage with Brian Jones and Anita Pallenberg, the flight to Morocco and Tangiers, the death at Altamont Speedway, tax exile, recording Exile on Main Street on the French Riviera – but they bear repetition. Like the court case, in which the Prosecutor asked if Keith thought it "normal" for a young woman to be found wearing only a fur rug in the presence of a Moroccan servant. Keith replied, "We are not old men. We are not worried about petty morals," and instantly won the hearts of a million teenage would-be rebels.

He is not afraid to portray himself as a prize shit. When describing Jagger's pursuit of Pallenberg, and his revenge, he addresses his old friend directly: "But, you know, while you were doing that, I was knocking Marianne, man. While you're missing it, I'm kissing it." It's not an edifying spectacle.

The narrative sometimes threatens to disappear beneath a spindrift of narcotics: heroin, cocaine, morphine, apomorphine, dimethyltriptamine, tuinol, mandrax, seconal, nembutal, desbutal, demerol, hashish, mescaline, peyote and, lowest of the low, "Mexican shoe scrapings". Richards admits that too many should-be-memorable occasions – such as a two-day trip to Torquay and Lyme Regis with John Lennon – are lost to drugs. It's amazing that he never died, but equally amazing that he survived so many criminal encounters and hair's-breadth escapes.

He admits he was once fooled by "Spanish Tony" Sanchez into driving the getaway car in a London jewel heist. Confronted on a narrow ledge in the Atlas Mountains by a rocket-carrying truck and four police motorcyclists, he drove straight at the police escort and heard, a moment later, both truck and rocket exploding miles below. Over the years, he looks down the barrel of several guns. He offers advice about how to proceed in a knife fight.

He once kneed the US impresario Robert Stigwood in the groin 16 times, "one for each grand he owed us". You lose count of the times he is almost nailed with a car-load of drugs and a policeman raising a hand. When he finally gets clean in 1978, and breaks up with Pallenberg, just before his trial in Toronto, you feel like cheering.

If the zenith of the Stones's success story was the epic 1972 tour ("We had become a pirate nation, moving on a huge scale under our own flag") the nadir was a decade later, when the principal players fell out. Richards is merciless about Jagger's "Lead Vocalist Syndrome," his conceit, his taking dance lessons (Jagger?) and, worst of all, his fondness for disco music. Not to mention Richards's – surely libellous – remarks about the great Lothario's "tiny todger."

He claims at the end that he's not just here to make records. "I'm here to say something and to touch other people, sometimes in a cry of desperation: 'Do you know this feeling?'" I don't actually think we do know the feeling of conquering the popular music world in your twenties, writing some of the finest songs in the rock canon, having millions of desirable women fling themselves at you, dodging the police forces of three continents or soiling your pants while climbing the wall during 72 hours of cold turkey. But thanks to this densely textured, vivid and utterly charming autobiography – far better-written and more coherent than anyone could have hoped – we're slightly closer to knowing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments