Life: An Exploded Diagram, By Mal Peet

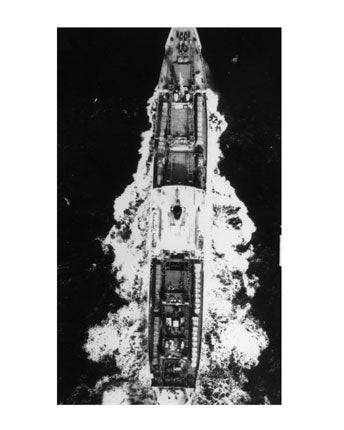

Sex and imminent nuclear annihilation come alive in the tale of a boy and girl finding love – just as Kennedy and Khrushchev lock horns over Cuba

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Sunday, 28 October, 1962, the Cold War military lunatics of Russia and America finally decided against blowing up most of the world.

Strange that there is no annual public celebration of this day, considering how events in and just outside Cuba at the time so nearly led to mass extermination. Authors since then have not been conspicuously interested in this episode either, happy to turn to apparently more urgent personal matters than the survival of everyday life. A big welcome therefore to Mal Peet's inelegantly titled but absorbing novel Life: An Exploded Diagram.

Even though readers know that the missile-bearing Soviet ships will eventually turn back, the tension here is still electrifying, made more so by Peet's habit of quoting verbatim from some of the hair-raising tactical advice actually proffered in White House meetings at the time.

This is not primarily a political novel. Most of it concentrates on the sixth-former Clem, named after the former prime minister Clement Atlee, and the passion he shares with Frankie, the daughter of a wealthy Norfolk landowner who employs Clem's father, George.

First love as a rite of passage is a common enough theme, but done well still comes across with the same urgency experienced by the young lovers themselves, oblivious to the fact that it has all happened to so many others before. And Peet does indeed describe it well. Rather than trade in the easy, unearned emotions of sentimentality he allows his characters doubt as well as certainty, with the final act of sexual fulfilment both a climax and something of a disappointment. A plot twist then blows everything up sky high, in this case quite literally. There are yet more surprises to come after that.

The story starts in leisurely fashion with the life and times of Clem's grandparents, leaving plenty of room after that for passing on to the muddled courtship of his mother and father. Such pre-main plot digressions can often be tedious, but Peet is Norfolk-bred himself and clearly feels he has earnt the right to enjoy revelling in details of his home county's rural eccentricity. Characters speak in broad dialect, easy enough to understand and also symbolic of a way of life as distant now as a Thomas Hardy novel. But there is little lingering sense of loss. As Clem himself puts it, writing after the event in middle-age: "Nostalgics want to cuddle the past like a puppy. But the past has bloody teeth and bad breath. I look into its mouth like a sorrowing dentist."

Physical details come instantly alive. George brings Clem's mother, Ruth, a silk shawl from his army days in North Africa; to her, it merely smells "whorishly of foreign parts". Young Frankie, coming over from France, learns to love her ancestral East Anglian home despite its scowling furniture and "peculiar food served in heaps". Clem's early sexual imaginings exist in "fingery darkness like woodlice under a brick". When he has his hair cut, the manual clippers the barber runs up his neck clack "like a mad dog's teeth".

Early on Clem assures his readers that he is not writing yet another teenage misery memoir, and has no desire to "add my small pebble to that avalanche of unhappiness". He is as good as his word. Despite its main subject matter, this is still a richly comic novel. There is a real sense of loss coming to its end even after 413 pages have whipped by.

Half-way through, major political figures start appearing as characters in their own right.

Khrushchev, "as hard as a drill-bit and as cunning as a lavatory rat", is shown telling his defence minister, Malinovsky, that it is time to "stick a hedgehog down Kennedy's shorts". In return, the American President, heavily drugged to relieve his constant state of pain, somehow manages to fight off the most hawkish of his generals.

The world meanwhile waits, and Clem – fired up by reading Andrew Marvell's poem "To His Coy Mistress" – decides that he and Frankie must finally make love properly while there is still time. At this stage, the story starts pulling in two different directions, with Peet increasingly appearing to forget his young lovers as he becomes more embroiled with current affairs.

But this is a minor fault. Previously the winner of both the Carnegie and Guardian awards for his teenage fiction, here is a gifted novelist who deserves the widest audience. His autobiographical account of Clem's schooldays at his ultra-patriotic grammar school where the National Anthem is played on every pretext, including the Duke of Kent's birthday and the anniversary of the Battle of the Nile, is just one of the pleasures of this irreverent and compassionate novel.

Read and enjoy.

To order any of these books at a reduced price, including free UK p&p, call Independent Books Direct on 0843 0600 030 or visit independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments