Keeping At It by Paul A Volcker with Christine Harper, review: Memoir delivers a powerful message

The former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board reflects on a life of public service

The title of Paul Volcker's new book, Keeping At It: The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government, tells readers quite a bit about the material they're about to consume. This is not a barnburner; rather, as the name quietly implies, it is a measured, even-handed review of a career largely spent in public service, including two terms as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Anyone expecting an explicit and full-throated rebuke of current political leadership in Washington or of President Trump, who has repeatedly attacked the Fed, will be disappointed: Volcker's memoir essentially ends in 2013, with the formation of the Volcker Alliance, a nonpartisan group that aims to improve the efficiency of government.

Nor is Keeping At It, written with Bloomberg Markets editor-in-chief Christine Harper, a salacious Washington tell-all. Volcker describes his gig as undersecretary of Treasury for monetary affairs for the Nixon White House – where he helped dismantle the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates – as “the best job in the world”, but he gives little explanation for his voluntary departure in early 1974 except to say, “The Nixon administration was in turmoil, consumed with the Watergate scandal what was transfixing the public.” If Volcker was witness to a presidency in chaos, he doesn't say.

His time as Fed chairman during Jimmy Carter's calamitous White House – Volcker's tenure overlapped with the Iran hostage crisis, the 1979 oil shock, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and runaway inflation – is covered in less than a chapter. And in describing his decision to complete his second term (he initially told both his wife and Ronald Reagan he'd serve only a few years of the four-year term), Volcker writes: “I ... got no open complaint, either from the White House or from my wife. President Reagan had his hands full with Irangate.” Nothing else is said of the arms-for-hostages scandal.

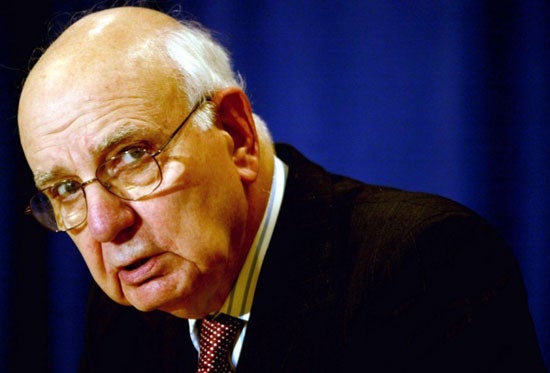

But make no mistake, Volcker has much to say, and the absence of bomb-throwing gives his message added weight. This is no central banker crying wolf. When the 91-year-old economist decries the role private interests have played in eroding sound money and good government, he offers plenty of firsthand evidence, from the savings-and-loan fiasco of the 1980s and 1990s to the financial crisis of 2008-09.

“The growth of money in politics is a major challenge to the democratic ideals we express,” he concludes. “We have learned time and again that years of financial stability and economic growth tend to involve easing of regulations and supervisory discipline. We see that at work as I write in 2018, with pleas for reduced capital standards for banks ... Can we learn to do better?”

Volcker, who is responsible for placing limits on Wall Street risk-taking as part of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, is unsparing in his criticism of lobbyists, whom he accuses of trafficking “fictions” about how the Volcker Rule would curb economic growth. He has no patience for bankers who spin the notion that their increasingly complex and risky financial instruments, designed to give them an edge in making money, are for the benefit of the broader economy.

He also takes aim at government agencies for failing to modernise in ways that would allow them to effectively regulate business and protect consumers. But he doesn't simply blame the bureaucrats; he bemoans that academic institutions, specifically his alma mater Princeton University, have abandoned the notion of training the next generation of public administrators, in favour of the more prestigious pursuit of churning out political scientists and economists.

It's a provocative argument, one Volcker believes in so strongly that he's formed a nonpartisan group that works to strengthen educational programmes for public service. As he writes: “Good government is dependent on good administration.” But Volcker offers little insight on the hard skills the city managers and treasury undersecretaries of tomorrow will need to be effective leaders. And his critique of Princeton (and by extension, other elite universities) for chasing prestige over practicality ignores the fact that there are hundreds of state schools and smaller colleges offering undergraduate and master's degrees in public service.

Still, Volcker is no elitist: He addresses the issue of income inequality, questioning whether today's bank CEOs have really earned packages five or 10 times larger than their predecessors' of 40 years ago. He says: “It doesn't show up in the economic growth rate, certainly not in the pay of the average worker, or, more specifically, in an absence of financial crises.” Throughout the book, Volcker underscores the idea that sound fiscal policies should be in service of citizens, not institutions.

Keeping At It is by no means a breezy read, but it has its lighter moments. The 6ft 7in Volcker shows he is capable of cutting people down to size – literally – when he writes of conservative economist Milton Friedman: “Friedman, fifteen years older than me and some sixteen inches shorter, surely ranks first among the most doctrinaire and persuasive economic gurus I have ever encountered.”

Volcker, who identifies himself as a political independent (despite endorsing Barack Obama's presidential run in 2008), is equally dismissive of dogmatic thinking by the Keynesians he met in graduate school. “Somehow, it seemed to me, the complexities of the economy couldn't be reduced so easily to so few variables.”

At a time when Americans have become accustomed to incendiary tweets, hot takes and instant punditry, the author's unhurried prose may seem quaint; the first half of the book can feel downright wonky. But by detailing his considerable work in the field, Volcker's reproaches are that much more credible. He ultimately delivers a powerful message – readers just need to keep at it.

Stephanie Mehta is editor in chief of Fast Company

Keeping At It is published by PublicAffairs

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks