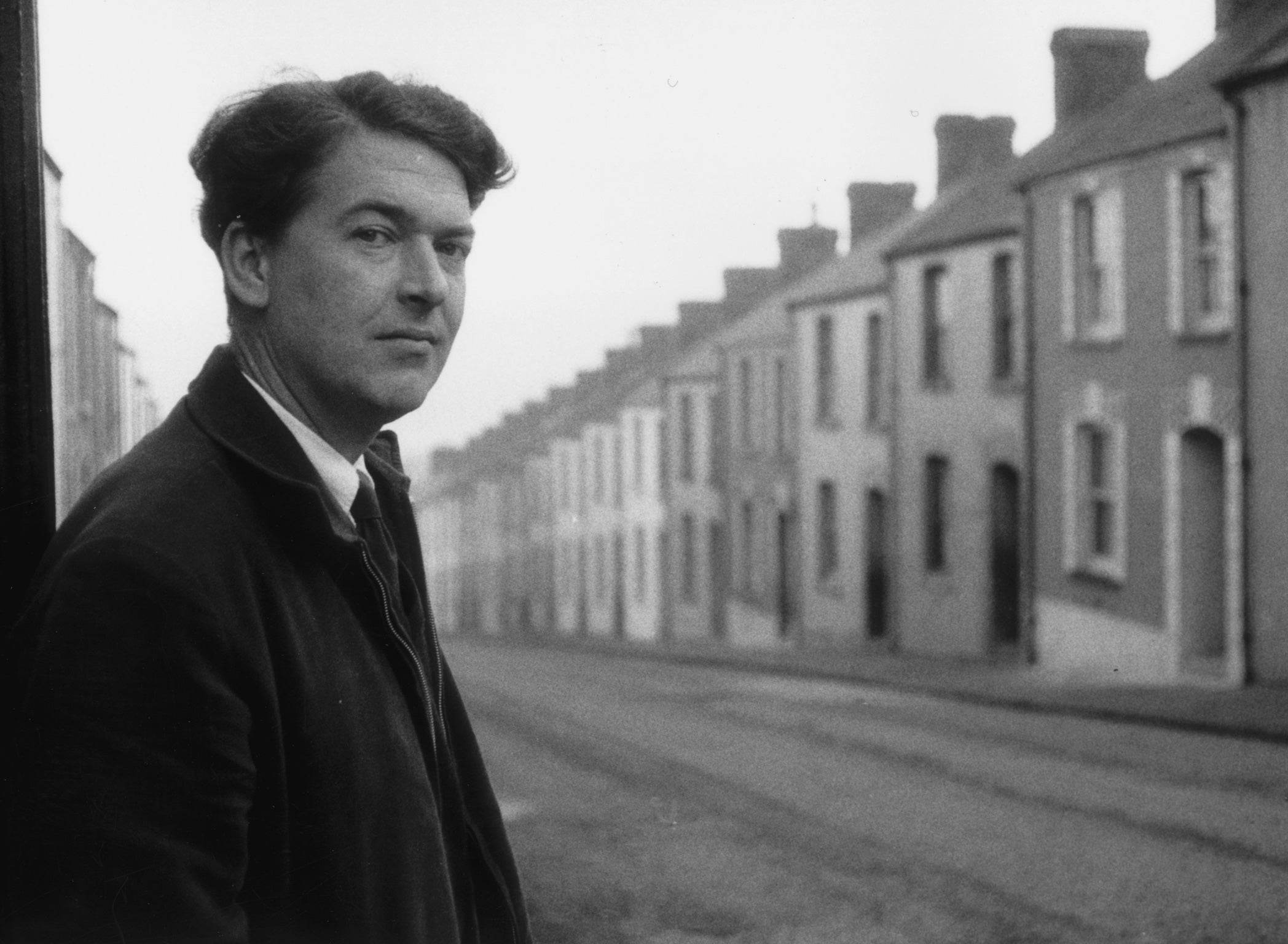

IoS book review: The Odd Couple: The Curious Friendship between Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, By Richard Bradford

Pedigree chums ... or how two literary old dogs finally fell out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.No one could ever accuse Richard Bradford of understatement. "During a 30-year period between the mid-1950s and the 1980s, Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin produced, respectively, the finest fiction and poetry of their era," runs The Odd Couple's far from disinterested opening sentence. Having filed these claims – number two more plausible than number one – he goes on to consider the extraordinary volume of material that the Amis-Larkin relationship has generated in the past quarter-century. My own bookshelf harbours at least eight works with some bearing on the case, including three biographies of Amis, two of Larkin, two lots of selected letters and Amis's own Memoirs. Surely one can have too much of a good thing?

In fact, Bradford, fresh from a sit-down with the surprisingly large number of letters that didn't make it into Zachary Leader's edition of Amis's correspondence, or Anthony Thwaite's edition of Larkin's, makes a good argument for his 350 pages' worth of fresh exegesis. The assumptions he begins with may be well-worn, but the series of close biographical re-readings to which he subjects them take nothing for granted.

His subjects first encountered each other as undergraduates in the front quadrangle of St John's College, Oxford in May 1941. Brought together by a liking for girls (Amis always the more hands-on), books and jazz, and a hatred of cant, pretension and being told what to do, they were soon embarked on a long voyage of private fantasy and the forging of what could almost be called a joint sensibility, in which each left tangible traces in the other's work. It was Larkin who gave Amis the idea for Lucky Jim (1954) by introducing him to the Leicester University senior common room in 1947; Larkin's 1950s poems, as Bradford shows with more ingenuity than many a previous Larkin critic, often reflect his responses to an Amis novel or a revelation from Amis's increasingly louche private life.

No doubt about it, Amis and Larkin loved each other with a passion undimmed by the presence of Amis's first wife Hilly, herself a Larkin fan who would happily have followed her husband to Belfast, where Larkin acquired a library job in 1950.

After 1952, on the other hand, the power balance began to shift. Not only did Amis burlesque Larkin's long-term girlfriend Monica Jones in Lucky Jim, but much of the book turned out to have cannibalised their private world. Larkin, always touchy when his privacy was at stake, suspected that Amis was exploiting their relationship in pursuit of his own literary success. Their personal lives, meanwhile, continued to diverge: Amis's into a boozy, satyromaniacal caper in the limelight; Larkin's into quiet, provincial misanthropy.

Bradford teases all this out with considerable artfulness and great sympathy, amid a sprinkling of tiny errors. Larkin, who died in 1985, could not, a fortiori, have been interviewed on The South Bank Show in 1986, and Amis could not have reviewed Richard Hoggart's The Uses of Literacy in 1956, the year before it was published. On the plus side, for a practising academic, Bradford has a cheeringly anti-academic style and rarely respects any of the reputations he runs up against. Mysteriously, there is life in these two old dogs yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments