In Zodiac Light, By Robert Edric

A moving portrait of breakdown, casual brutality and locked-in creativity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

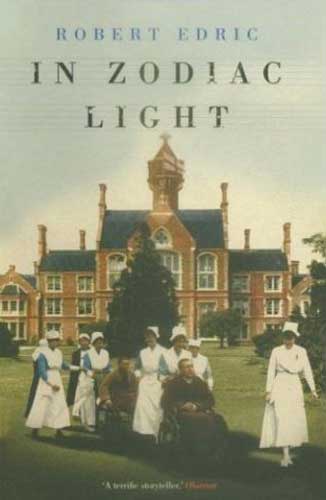

Your support makes all the difference.After service in the First World War, the poet and composer Ivor Gurney led a strange, wandering existence marked by periods of intense creative work and mental breakdown. In 1922, he was committed to the City of London Mental Hospital at Dartford, Kent. He continued to write until 1926, then fell silent. A visitor described him as a "tall, gaunt, dishevelled figure" living in a "bare and drab" cell. He remained there until his death from tuberculosis in 1937.

The first year of Gurney's confinement is the subject of Robert Edric's novel. The narrator, a young doctor called Irvine, is bewildered by the casual brutality of the orderlies and the cynicism of the medical staff. Edric's portrayal of this institution is certainly powerful, but the Dartford Hospital was a real place, and the description simply does not ring true. The constant insolence voiced by orderlies to doctors and nurses is quite unbelievable. I don't believe that in the rigid hierarchy of hospitals at that time such insubordination would have been tolerated.

Gurney does not appear until a third of the way through, but when he does the novel takes flight. This is a fine portrait of an acutely sensitive man tortured by imagined electrical waves and delusions of grandeur. The former soldier shares a room with a young man, Lyle, a conscientious objector. Lyle has been tortured in prison and is not mad, but knows that he has little chance of escaping the madhouse that is an extension of his punishment.

He encourages Gurney to write and is jealous of the visitor, Marion Scott, who takes Gurney's work back to the outside world. Irvine wants to help both men and arranges for them to help him restore beehives in the grounds. There are brilliantly rendered flashbacks to Irvine's home life and his father's obsession with bees; the decay of the hives is a central symbol of a benign but locked-in creativity.

The novel builds to twin climaxes – of a concert arranged inside the asylum to play Gurney's works, and the tragedy that befalls Lyle. The novel works best in Gurney's conversations and Irvine's memories. Most movingly, it suggests the terrible thought Gurney expressed in "To God", one of his asylum poems: "Not half can be written of cruelty of man, on man,/ Not often such evil guessed as between man and man".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments