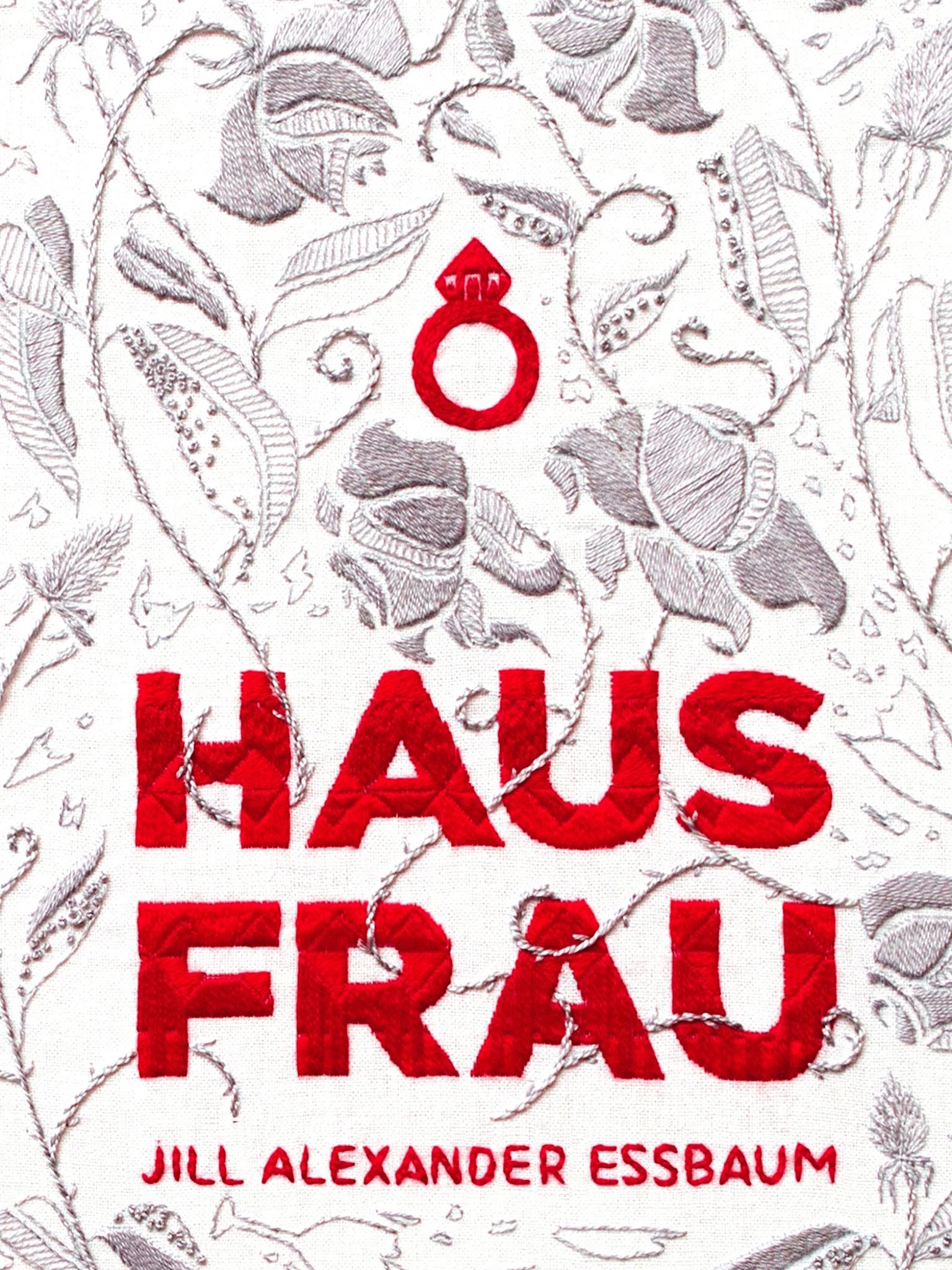

Hausfrau by Jill Alexander - book review: Affairs of a distant heart

It's refreshing to discover a female protagonist who is allowed to be quite such a casual wife

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“It’s an absolute fact: Swiss trains run on time,” we are told at the start of Jill Alexander Essbaum’s debut novel. Anna, the hausfrau of the title, is riding on one of those predictable trains, a passenger in every sense.

She endures a stultifying existence in the Zurich suburbs with her husband Bruno and their two sons. Outwardly, her life belongs to a different era: she does not drive, or earn her own money, or even have a bank account. An American expat, she barely speaks the language of her new home.

All is not as it seems, because Anna is “a good wife, mostly”. She meets fellow student Archie in her German class and begins an affair with him, leaving her children in their grandmother’s care and indulging in sex remarkable as much for its emotional detachment as for its infidelity. Moreover, Archie is not the first. “Some women collected spoons. Anna collected lovers.”

There are echoes in Hausfrau of those other frustrated wives, Emma Bovary and Anna Karenina. Here, as in those novels, we expect tragedy at the turn of every page, though I also found myself longing for this to be one story in which a transgressive woman does not, after all, get her just deserts. Torn between the identities of docile housewife and erotic adventuress, Anna is fragmented.

Essbaum is an acclaimed poet and at moments her prose takes on a lyrical concentration. Scottish Archie speaks “a queue of vowels rammed into one another like asmithy’s bellows pressed hotly closed”.

Anna imagines a Spanish lover “with matador hands”. Reflecting on her body, she considers “the deadbolt room of her pelvis, where she tended to file her grievances with the world”.

Anna’s emotional distance applies as much to the reader’s connection with her as it does to her relationships with others. Rather like her own experience of those sexual assignations, we find much here that is interesting, less that engages. But it’s refreshing to discover a female protagonist who is allowed to be quite such a casual wife, such a detached mother, such an unromantic lover. (“Put it in, take it out. Repeat for as long as possible.”) That, in the end, is the subversive thing about Anna: not her libido or her secret affairs, but her refusal to feel quite as copiously as women are expected to, her refusal to make herself likeable. She neither courts our approval nor dodges our judgement.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments