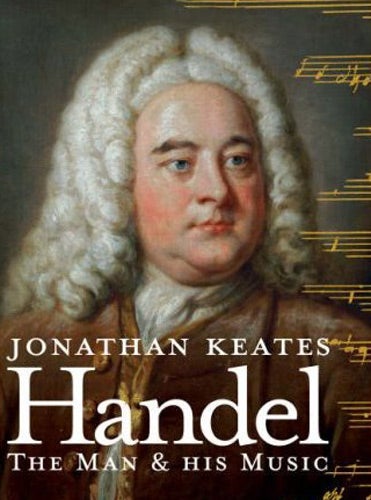

Handel: the man and his music, By Jonathan Keates

Guide to the art of a composer hits the high notes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Since celebrity culture has put sex at the heart of biography, Handel has lost out. As Jonathan Keates observes, there's no documentary evidence on that aspect of his private life, so all we can do is conjecture. But he was well-built, handsome and assured, and his operas suggest a profound understanding of heterosexual sensuality. Keates suggests his peripatetic professional life was a likelier bar to marriage than the oft-alleged closet gayness.

This expanded edition of a book Keates published 23 years ago takes in a wealth of new knowledge, and combines biographical and musicological analysis in a way that will appeal both to the general reader and the aficionado. Handel's early years come into high relief: his stubborn attachment to music (smuggling a clavichord into his room, despite his doctor-father's prohibition), his literary education in Protestant Halle, and his teenage appointment as a church organist, are seen to shape the phenomenal talents that served his genius.

Keates is illuminating on Handel's early journey to Italy as a keyboard virtuoso and budding composer. In Venice, he was sought out by an admiring Scarlatti, while in Rome he fell under Corelli's benign influence; he was ravished by the pifferari music played in the street by Abruzzi shepherds, which he later reproduced in his Messiah. In Rome, he encountered the cantata, a form he quickly made his own. When he arrived in London aged 25, the city was as ready for him as he was for it.

George I became Handel's enthusiastic patron, as did Queen Anne. London's opera-mania provided the perfect climate in which Handel could blossom. Keates follows the sinuous thread of his career: helping launch the Royal Academy, collecting castrati and sopranos, building his first company and becoming rich, then hitting choppy waters as competition spurred by political divisions threatened to put him out of business.

With its astute commentaries on the operas, this book makes a brilliantly lucid guide to Handel's evolving art. Though anecdotes remain scanty – most reflecting Handel's gastronomy and famously short fuse – Keates fleshes him out without resorting to novelettish invention. How English was he? Not very, despite the citizenship he claimed. His thick "Cherman" accent was mocked. But he was admired and loved: his progressive blindness and gracefully uncomplaining death led to universal mourning, followed by an even greater surge in his music's popularity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments