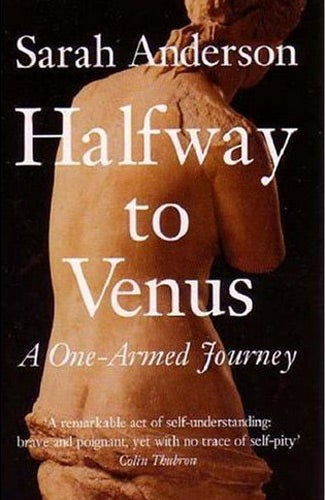

Halfway to Venus, By Sarah Anderson

True story of a woman who lost her arm but found courage and success

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At first sight, you could be forgiven for thinking that Halfway to Venus, a "one-armed journey", was going to be a "poor me" book. But what makes it so different is that, despite having had her arm amputated due to cancer when she was 10, Sarah Anderson is at pains to tell us that she's far from sorry for herself. Angry – yes. Understandable fury drives the book along to an ending that resolves in self-acceptance and a certain courage.

Anderson has made a great success of her life. She started up the Travel Bookshop in west London (yes, the one that featured in the famous movie Notting Hill; she has had to suffer gawpers ever since). She has self-published two books; she has scuba-dived, trekked, swum, made love, driven, written extensively and even, in a hilarious final chapter, signed on to a One Arm Dove Hunt in the US, especially designed for people who have lost an arm.

Her personal story is desperately poignant. Her mother, unable to tell her verbally what would happen when she went into hospital to have the operation, instead made a chopping motion with her hand across her arm. Afterwards, almost nothing was said: no counselling; no therapy. Her parents even bought her a bicycle and expected her to get on with it. Which she did. Far from feeling resentful, Anderson is grateful now that her difference wasn't singled out, and that no fuss was made of the situation.

She faced lots of inevitable battles. One writer took her out twice to dinner and, on the second occasion, asked what had happened to her arm. When she told him, she never saw him again. But it's the small things that are most memorable – the member of staff at the British Museum who refused to open the door for her when she was carrying books; the fact that she's unable to hold a drink in her hand and eat canapés at the same time; the opening of bottles, and all the irritating setbacks she faces daily – things that us two-armers take for granted.

Part autobiography, part a foray into the social and historical meaning of "one-arm-ness" , this is a readable and haunting book. You don't put it down with the feeling of "Thank God, I've got two arms", but more with admiration for a woman who has come to terms with her situation so successfully.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments