Funny Girl by Nick Hornby, book review: The rise and faltering of a sitcom star

It's a promising trajectory but Hornby abandons his funny girl for more of his hapless men

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

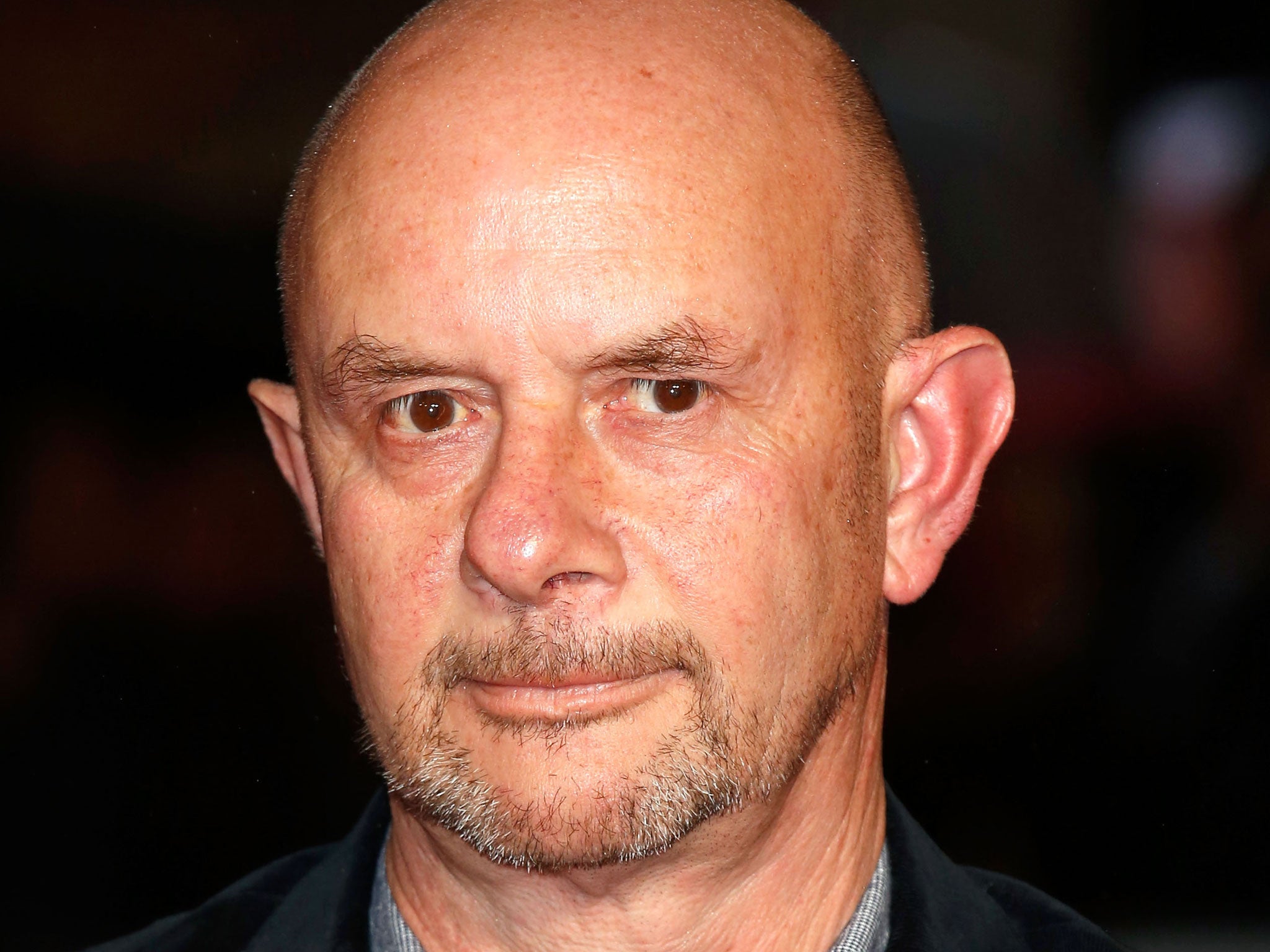

Your support makes all the difference.This is Nick Hornby's first novel in five years, since he diverted into films and was Oscar-nominated for his screenplay for An Education. That experience has filtered into Funny Girl, which is about the making of a sitcom and so is, on one level, a novel about screenwriting. And, like An Education, it is set in a Britain on the cusp, poised between the buttoned-up Fifties and the let-loose Sixties.

Hornby has had a bit of fun making it read like something between social history, biography and novel: there are fake newspaper articles and encounters with Harold Wilson and The Yardbirds, pictures of mocked-up scripts and archive photographs of beauty contests, BBC personalities and Mick Jagger. You can all but smell the Coty perfume and Babycham wafting off the page.

The funny girl of the title is Barbara Parker, a stunner "with Gaye Gambol's wasp waist, large bust, blonde hair and big, fluttery eyelashes" – and with a bolshie determination to become Britain's answer to Lucille Ball. It starts out as quite a tract – a Northern lass tries to make it as a comedienne at a time when women were looked at rather than laughed at. Nothing – not her Blackpool vowels, not a father on a death bed, nor an agent keen to have her stripped and covered in gold paint by a Bond villain – stands in Barbara's way. She goes from winner of Miss Blackpool to London department store dolly to star of a mould-breaking BBC marital sitcom, "Barbara (and Jim)", all in the first 50 pages.

It's a promising trajectory but once Barbara sets about becoming the nation's sweetheart, she rather runs out of steam. And while Hornby tells us repeatedly that she is an "extraordinarily gifted" comic talent, she never comes across as very funny on the page. The male characters get all the best lines, and as the novel progresses, Barbara becomes more of a cipher for the male psychodramas playing out around her.

Hornby, of course, excels at these. The central drama is that of Tony Holmes and Bill Gardiner – symbiotic sitcom writers in the style of Galton and Simpson or Clement and La Frenais, who meet in a police cell in Aldershot in 1959. Arrested for importuning, they bond by quoting chunks of Hancock's Half Hour at each other. As the years pass, that bond is tested by their differing takes on both sexuality and sitcoms.

It's a risky business writing about writers. Hornby captures comically the frustrations of a BBC brief, the wrangling over titles, and the fact that no joke stays funny for very long. There are lovely insights into the writer's life: however successful you are, you will never be "Saturday night famous" in the eyes of the hippest restaurants. ("Take her out on Tuesday night and you'll be alright.") There is also a lot of talk about the merits of populism. Take this aside about a snobbish editor at Penguin: "What a terrible thing an education was, he thought, if it produced the kind of mind that despised entertainment and the people who valued it?" Who is really talking here? Hornby's hero or Hornby?

In trying to give an overall flavour of the era, Hornby leaves some of his many story strands underdeveloped. Still, his characterisation is spot-on, from Clive Richardson, the middling, priapic actor who plays the reluctantly bracketed Jim, to minor turns such as Barbara's psychotic flatmate Marjorie, and the insufferably prissy cultural commentator Vernon Whitfield.

Funny Girl is vivid, sparky and a bit schmaltzy, and it rattles along. But it's a shame that Hornby abandons his funny girl halfway through for more of his hapless men.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments