Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting by Catherine Lampert, book review: Portrait of the artist as no ordinary man

A new life of Frank Auerbach uncovers the agonies and ecstasies of a creative genius

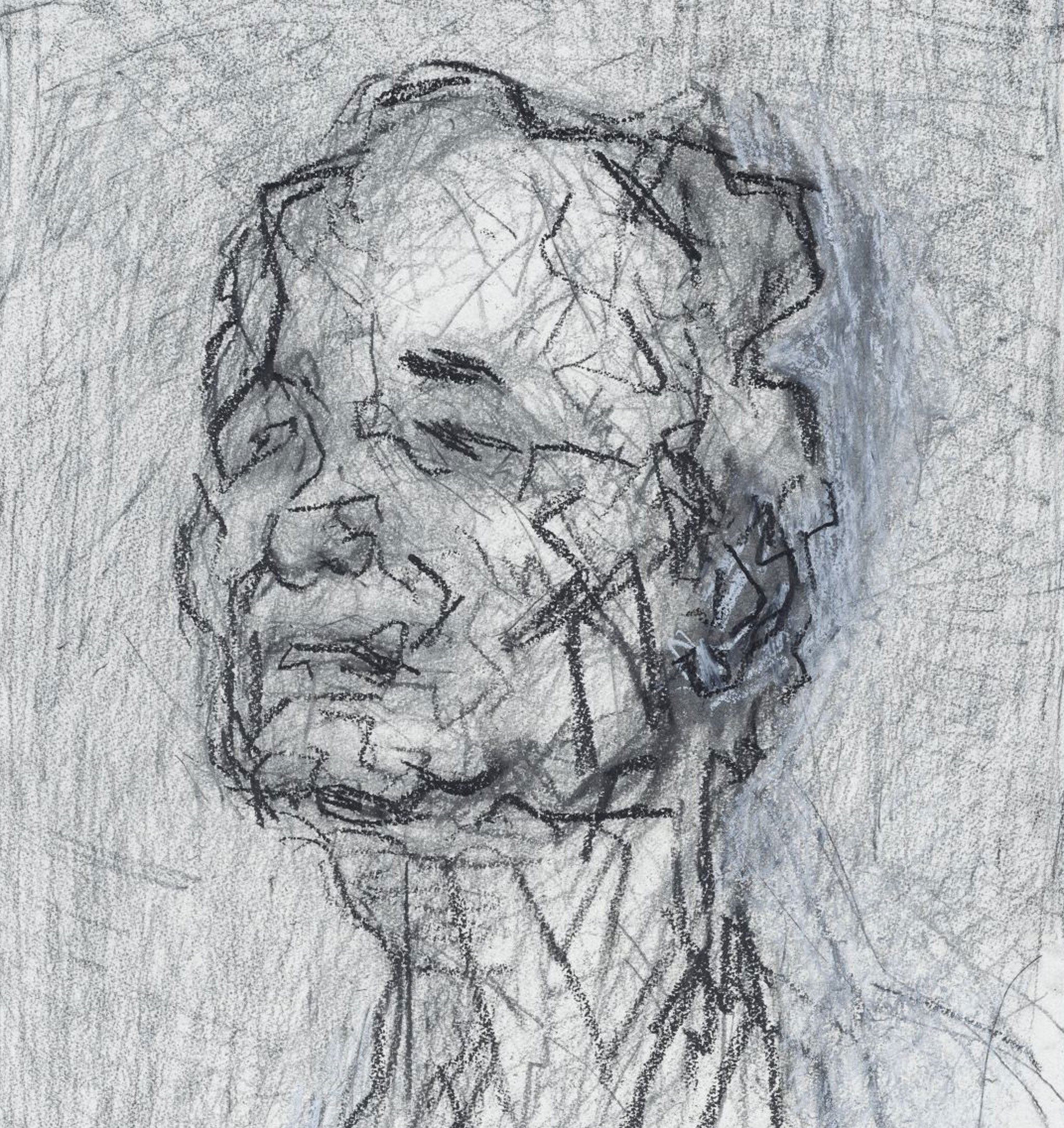

This autumn tate Britain will present a retrospective of paintings and drawings by Frank Auerbach, now 84 and arguably Britain's greatest living artist. It will provide a welcome opportunity to examine his entire oeuvre, from the thickly-caked canvases that first made his name in the 1950s, to his recent studies of the streets around the Camden Town studio he has occupied for over 60 years.

To the reclusive Auerbach's disgust, no doubt, it will also occasion fresh interest in his private life, and this proto-biography is surely a way of deflecting that. As the curator of the Tate show, as well as friend and model to Auerbach for nearly 40 years, Catherine Lampert is a safe pair of hands. But don't let that put you off. For a start the book's a beautiful object, full of superb reproductions and photos by John Deakin, Bruce Bernard and others.

Lampert clearly understands the allure of Auerbach's dark and troubled past and is willing to ask some difficult questions. For example, as a child born to Jewish parents in Berlin in 1931 and sent to England, aged just eight, only to discover later that his mother and father had been murdered at Auschwitz, how does he feel? "I think I did this thing which psychiatrists frown on. I am in total denial. It's worked very well for me," is Auerbach's answer, which to a younger generation brought up to believe in the benefits of therapy is anathema. "There's just never been a point in my life when I felt I wish I had parents," he adds.

That's his official line, but it's impossible not to look for sublimated trauma in his work and behaviour. After all, Auerbach has lived no ordinary life. When he enrolled at art school in London in 1948, aged 17, he moved into a rented room and began an affair with his landlady, Stella West, a widow of 32. "He was very violent and quite in a world of his own," she recalled. Stella continued to be his muse and lover until 1973, even after he married his wife, Julia, and became a father to their son, Jake, in 1958. Later, after a period of 16 years apart, he and Julia reunited and he continues to paint her to this day. This obsessive documenting of the people he loves, he explains, is partly his attempt to grant them immortality.

Lampert's descriptions of Auerbach's working methods also give insight into his compulsive behaviour. Each of his monumental pictures can take years to make, beginning with over 200 sketches, followed by months of layering paint onto a canvas, only to scrape it off 300 or 400 times and start again, before the picture becomes "an object like nothing on earth".

Auerbach's learning from great artists is as thickly layered as his paint. After reading this book it's a revelation to see in his pictures the teachings of Titian and Veronese, Turner and Constable, Vuillard and Matisse. There's also good stuff on his friendships with Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, who bought him his first lobster dinner in 1956.

This is a terrific read, but there are omissions. How did Auerbach's family really feel about his erratic commitment? Why did he object so strongly to WG Sebald's fictionalised account of his life in The Emigrants? And, considering he says he lived on tahini and rice until his fifties, how does he feel about the recent £2.3m record price for his work? Nevertheless it's a tantalising start to what will surely become the Auerbach life writing industry, and it only leaves you longing for more.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments