Everything is Teeth by Evie Wyld; Illustration by Joe Sumner, book review

Evie Wyld's graphic memoir details her enduring fascination with the great predators, and with what lies beneath it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fear and obsession can be joined in a Möbius-strip linkage. No one understands this better than Evie Wyld, who, as a girl growing up in South London, first encountered sharks in coastal New South Wales, where she used to go on holiday with her parents and older brother to her uncle's home every Christmas. The encounters, mercifully, were not real or physical, but rather cultural and imaginative: stories heard from New South Wales natives; a visit to a shark museum with her father; seeing Jaws (of course); discovering books by Rodney Fox, the world's most famous survivor of a brutal shark attack.

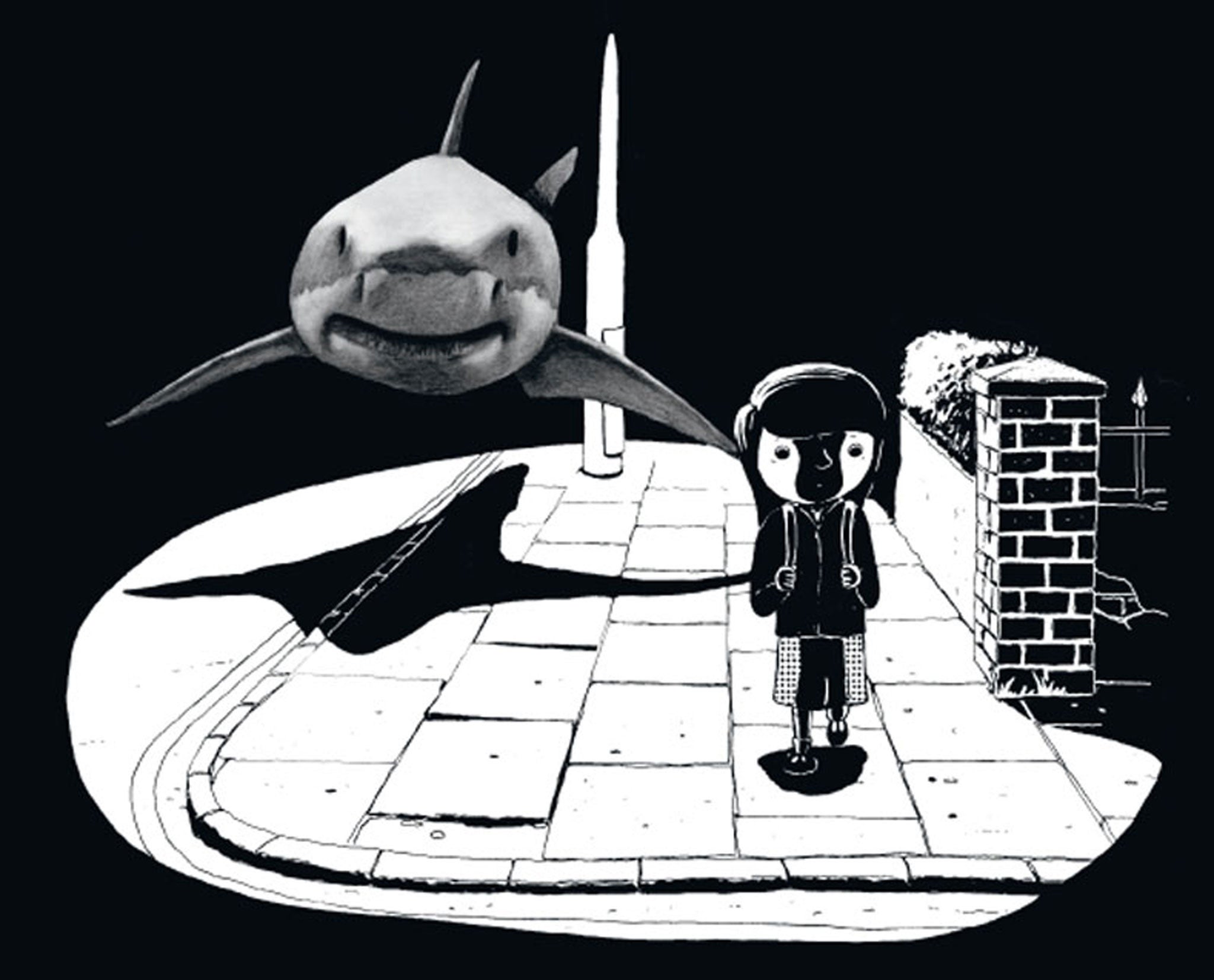

One of the most acclaimed among the new generation of British writers, with two beautiful, award-winning novels, After the Fire, A Still Small Voice (2009) and All the Birds, Singing (2013), under her belt, Wyld has teamed up with illustrator Joe Sumner to produce a moving, heartfelt, original book in which the interior world of the imagination is more real than the external world. This is an inalienably truthful quality of childhood and Sumner has rendered it beautifully – a shark lurking in the cornfields besides which Evie walks, another floating in mid-air, reflected in the rear-view mirror of the car in which she is riding, or behind her, suspended, and casting a hulking shadow on the street she walks on.

And yet this all-consuming imaginative engagement with a predator is like the shark's fin visible above the water's surface, for under it lies the real thing: the world of adults and their emotions and conflicts. This aspect of the book is only hinted at; and so subtly that the image and idea of the shark become, at times, a metaphor for that submerged, partially visible domain. There is the business of an older brother being physically bullied at school, and the tender relationship between a troubled father and his adoring daughter. The affective tectonic plates shifting so subtly under the surface of the visible landscape of pictures and words prove to be as compelling as the obvious story of summers spent in shark territory, especially in the book's coda, in which "a lot changes with time" and the Great Fear, of losing a loved one, comes true and the metaphorical becomes the real. It feels as if Wyld has wrapped up the emotional core of her childhood and presented it to her late father as a kind of goodbye present.

Sumner's artwork is wondrous, the perfect visual correlative to Wyld's spare lyricism. Can artwork ever be laconic? Choosing not to give the characters facial expressions, apart from one panel in which Evie is goggle-eyed with fascinated terror, is a masterstroke; in both words and pictures, the unsaid/unseen churns powerfully underneath. But let this not fool you into thinking that he cannot do traditional mimetic drawing: just look at his reproduction of scenes from Jaws unfolding on the television. His minimal colour palette, black and white and a bleached, straw-coloured yellow that powerfully conveys the December heat in New South Wales, makes the occasional burst of the red of blood shockingly effective.

But beyond all this, the book is unusual for yet another reason. In these times of culturally sanctioned self-absorption and self-promotion, with navel-gazing novels from Knausgaard and the New Brooklyn Solipsists providing à la mode book-chatterers with fodder for much panting nonsense, and professional literary-scene hangers-on tweeting about literary prize winners with the prefix "My pick" (yes, yes, it's all about you, darling), it is remarkable how an autobiographical – I stress this – book can enact a movement away from the self and become the repository of so much humility.

The humility is of the real, truthful kind, not the performative version that has given rise to, say, the term "humblebragging". How did she do it?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments