England and Other Stories by Graham Swift, book review: Swift's exquisite stories feature a world of mundanity and quiet desperation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

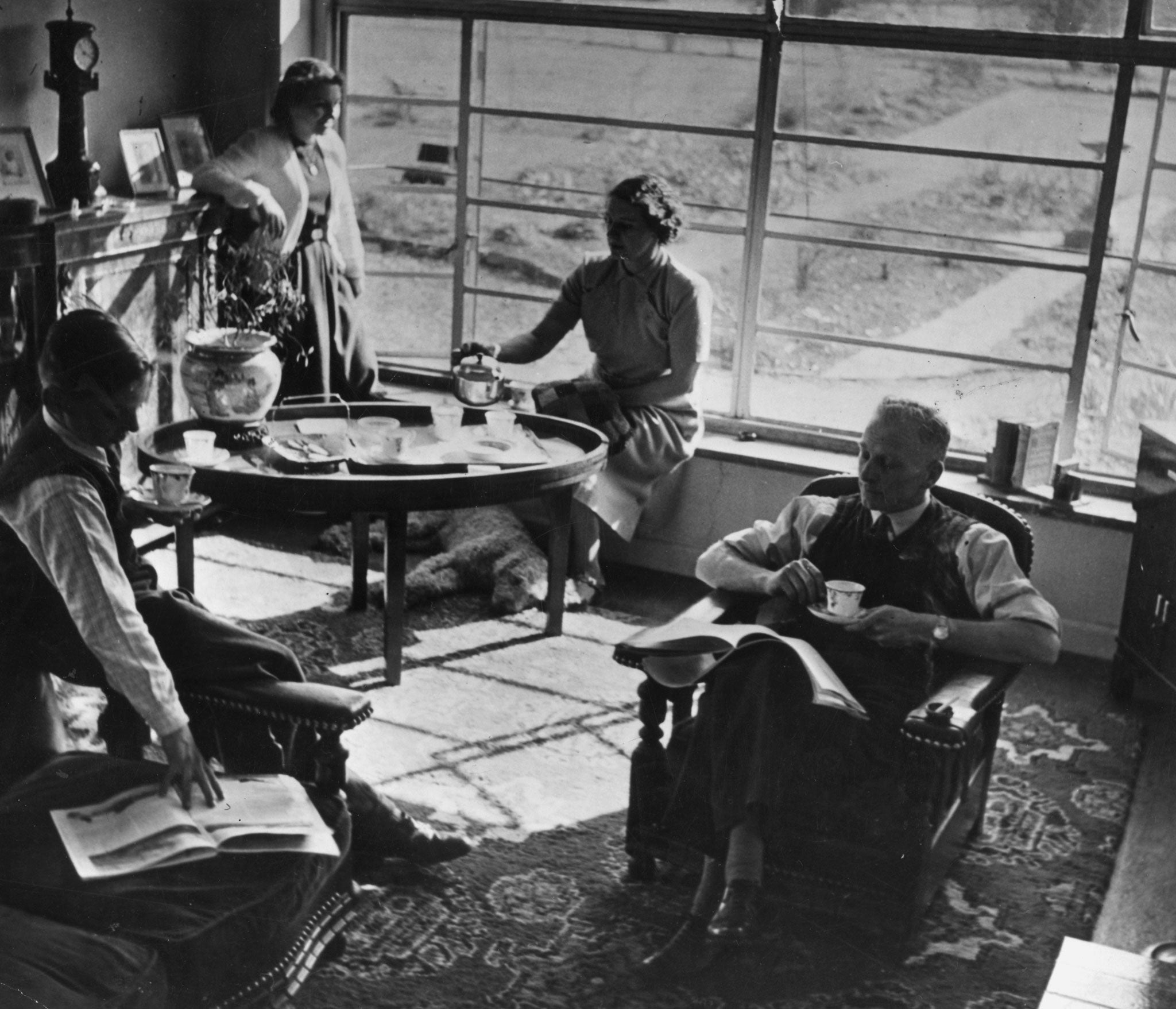

Your support makes all the difference.Graham Swift's characters lead lives of quiet desperation. They are not rich or poor, unemployed or exceptional. This is middle management middle England; a crap-town, dull job, post-Empire, not-very-good-at football, boring postcard kind of country with only a few moments to alleviate the silent tedium before the final trip to the crem. Death, or the memory of it, is never far away.

A widowed osteopath takes a new girlfriend but is convinced his wife is watching when they make love; a lawyer is told he has a terminal illness and pictures all the friends who have died before him.

The story Yorkshire begins: "Nobody spoke, nobody said anything. They spoke about the dead who couldn't speak back, they stood around with poppies, but the ones still alive, they shut up and got on with it. Wasn't that the best way, anyway, of being grateful to the dead? It's what you did, it's what everyone did."

Memory is ever present unless you are very old and then, if you are in a Graham Swift story, you get Alzheimers. Characters think back to their past, remembering a school cricket match, an impassioned love letter or a wedding day, and try to work out how much those moments may have contributed to the current state of "affairs", even if that word, incorporating the implication of adultery, isn't an accurate term for the common lot, the diurnal round.

Swift is particularly interested in the language of the mundane. Is it really a "tragedy" when a fork-lift truck driver dies of a heart attack? What does it mean to look "decent" (rather than " a right little whore,") or to have "a weirdo" living next door? The word "weirdo" is at the heart of one of the collection's best stories, Ajax, in which a man prone to exercising in his back garden, dressed only in his underpants, wonders how one of the major Greek heroes should have given his name to a household cleaning product.

"How has it come to this? How did any of us ever get to where we are?" the characters seem to be asking themselves. These people expected so much more of their lives but here they are, rescuing a child from a dog in the park, shagging the next door neighbour's Moldovan cleaning lady, or remembering their dead son, killed in Afghanistan, while standing by the pasta shelf in Waitrose.

Although his England of the title stretches from Yorkshire to Yeovil we are never far from the familiar suburbia of Swift's previous work: the Wimbledon setting of The Light of Day; the Bermondsey of Last Orders; the Clapham of Shuttlecock.

"People are Life", says the Cypriot barber before patting his clients on the shoulder and telling them to go on their way. "Don't you think there should be as much love as possible?" a man asks his best friend's wife. Yet such questions are not answered. The best we can do is survive. The story Dog has the following depressing apercu: "His father had once said to him, 'Money doesn't buy you happiness, Adrian, but it helps you to be miserable in comfort.'"

Yet despite the "familiar desolation" these stories are "oddly animating", neatly constructed but open-ended, in which characters attempt to join the dots to find some kind of picture only to abandon the exercise half-way through, leaving the puzzle unfinished. They are parables, cautionary tales, fables without a moral. What is not said is as important as what can't be told. Sometimes life has no meaning. You just have to get on with it before it's gone.

James Runcie is Head of Literature at the Southbank Centre, London. His latest novel is 'Sidney Chambers and the Problem of Evil'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments