Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Unexamined Life of a Mass Murderer by Bettina Stangneth, book review

This moving and disturbing study charts the post-war life of the architect of the Holocaust

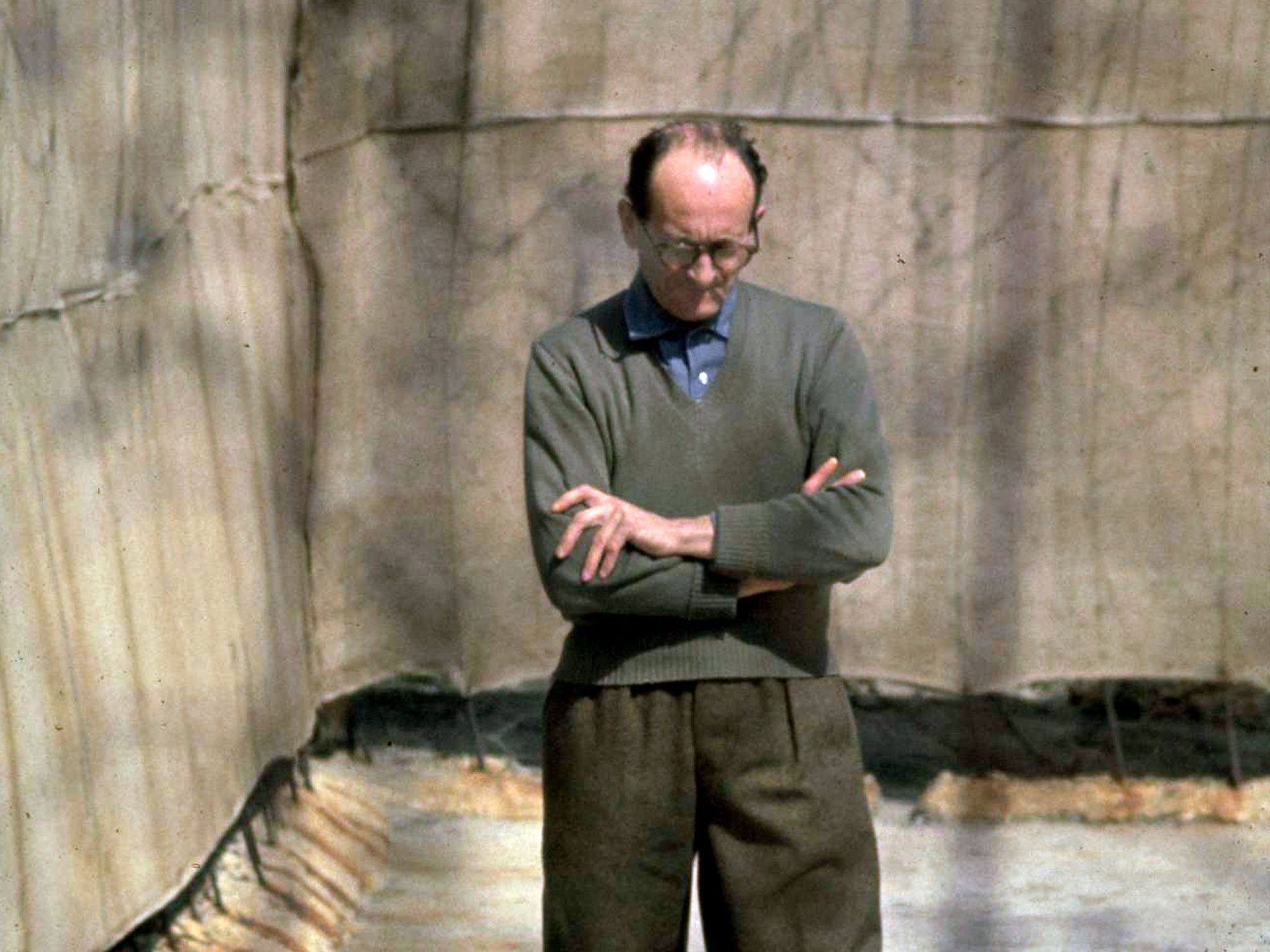

One question screams from the pages of this book. How did the architect of the destruction of millions of European Jews remain at liberty for 15 years? The answer is uncomfortable and complex, as seen in this powerful account of the life of Adolf Eichmann after the end of the Second World War.

Eichmann was the Nazis' "Adviser on Jewish Affairs". He ran the office of the Security Service that initially sought to force Jews to emigrate from Germany. When the war started, Eichmann organised Jews into concentration camps. Following the Wannsee Conference of 1942, he planned and implemented the German policy of extermination, taking particular responsibility for the death of three quarters of the Jews of Hungary

Eichmann's detached approach to mass extermination was summed up in Hannah Arendt's famous phrase "the banality of evil". In many respects, though, Bettina Stangneth finds herself in complete disagreement with Arendt over her assessment of Eichmann. Stangneth rates his intelligence much more highly than Arendt, who refers to his "modest mental gifts". She describes Arendt's judgement as "over hasty and dangerous" and says that she lacked familiarity with much of Eichmann's writings on philosophy, particularly Immanuel Kant's, whose ideas he appropriated for his own ends. Stangneth has respect for Eichmann to the extent that he was "capable of powerful arguments", and in this she shares her view with Eichmann's interrogator in Israel, Avner Less, who described the Nazi as "very intelligent, very skilful".

Eichmann made no secret of his heinous culpability. Towards the end of the war, he said he would "leap laughing into the grave because the feeling that he had five million people on his conscience would be for him a source of extraordinary satisfaction." He had no remorse for his actions. He told his interviewer and Nazi journalist, Willem Sassen: "I have no regrets; I am certainly not going to bow down to that cross... I balk inwardly at saying that we did anything wrong." Stangneth's use of the Sassen interviews and Eichmann's own notes written in exile give unusual insights into a mind that was rambling, philosophical, and lacked all self-doubt.

So why was someone who implemented extermination so zealously allowed to stay so long at liberty? The answer comes in two parts, according to Stangneth. Firstly, during the late-Forties and early-Fifties, the full scale of the Holocaust had yet to be properly comprehended. Stangneth says, "The number of six million seemed so extraordinary that people needed more evidence and explanations to make it even remotely comprehensible." Knowledge about Eichmann's role was likewise sketchy. His name was scarcely mentioned at the Nuremberg trials. Coupled with ignorance was incompetence, indifference and complicity by intelligence and police services.

Complicity came at many levels. Eichmann routinely received the help of an organisation of ex-Nazis to move from Germany to Austria, complete with a new name and a job as a chicken farmer. People smugglers then furnished documents for his flight to Argentina in 1950, providing him with a new identity as "Ricardo Klement".

German intelligence, the Gehlen Organisation, was presented with evidence of Eichmann's changing identities and locations, but sat on a report of his whereabouts, failing to act even when the facts were clear. One report emanated from a visit by Eichmann's wife and children to the Buenos Aires embassy for their passport renewals. Stangneth reflects: "There could hardly have been a more precise clue as to where Eichmann was... the employees of the German intelligence service should at least have been able to manage a job one might assign to a newspaper intern." The embassy's staff had no particular interest in coming to terms with Germany's past, according to Stangneth. "Eichmann came to the welcome realisation that he was surrounded by willing helpers."

The vigour of the hunt for the former Nazis was waning by the mid-Fifties and increasing numbers of Nazi exiles were returning from Argentina to Germany, confident that they could blend back into normal civilian life. So Josef Mengele returned to Germany to get divorced while others started to come back and look for wives.

A different level of notoriety attached itself to Eichmann as the scale of the Holocaust became evident. Indeed, there is the suspicion that some former Nazis thought that he might present a danger to them. Many were trying to salvage their reputations by denying the Holocaust, but Eichmann was known to be proud of the central part he played in it.

His name eventually entered the list of Germany's most wanted men in 1957, after information was passed on to the Nazi hunter Fritz Bauer. An arrest warrant was issued saying "it suspected Eichmann of killing people in numbers that cannot be precisely established in a cruel and underhand manner..." Bauer's investigations were unwelcome in Germany, Stangneth claims, and Eichmann was left to preach his messages of hatred in Argentina for another three years. In what now appears a clear case of incompetence, the German Federal Office of Criminal Investigation even said that "fundamental things about the case prevented an Interpol search".

The hunt for Eichmann, as told by Stangneth, is as fascinating as it is frustrating. Israel's move on Eichmann's house in a suburb of Buenos Aires, on 11 May 1960, brought it to an end, so many years on from the vast, and calculated, loss of life that he had engineered. He was charged with 15 counts, including crimes against humanity. His execution came in 1962. Eichmann's extended period of freedom raises a raft of questions about the scale of German complicity in the protection of this mythic character from their Nazi past. This extraordinarily moving book also indicates that the Eichmann question continues to haunt Germany.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments