Edward Heath: The Authorised Biography, By Philip Ziegler

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ted Heath is remarkable among 20th-century prime ministers in that he held office for less than four years (1970-1974), during which practically everything he tried to do failed dismally. Yet by the single act of taking Britain into the European Community, he left a more decisive legacy than many PMs who enjoyed far longer terms.

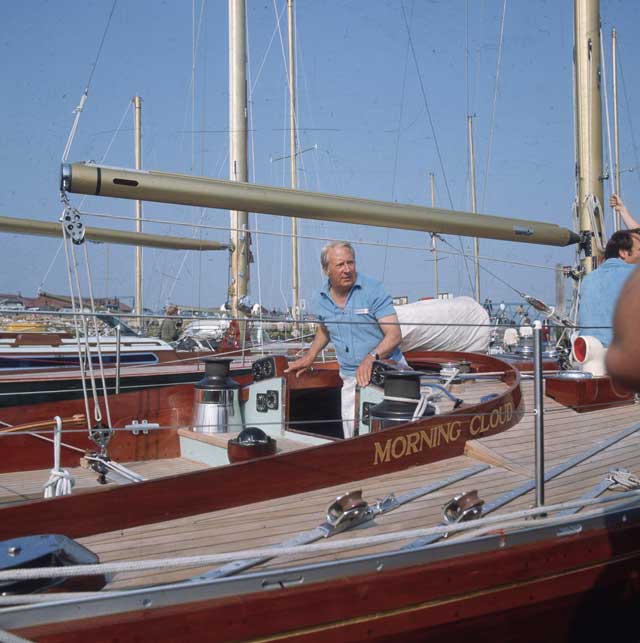

That is just one paradox among many that surround this baffling man. Politically, Heath saw himself as a modernising healer, yet he was reviled by Labour as the most reactionary prime minister since Lord Liverpool (at least until Mrs Thatcher came along), and simultaneously by much of his own party as a flabby semi-socialist. Personally, with his near-professional musicianship and his international achievements as an ocean racer, he was the most multi-talented politician of his day; yet he came across as a wooden, one-dimensional automaton chronically unable to communicate with either his colleagues or the public. The mystery is how such a deeply introverted man ever managed to become PM in the first place.

So Heath sets a special challenge to the biographer: 17 years ago - already nearly 25 years after he left office – I dared to write, without his approval or papers, a full, unauthorised but not unfriendly account of his life and government. He claimed not to have read it, but Philip Ziegler reveals that his copy is covered with furious comments scrawled in the margins.

I genuinely hoped that his memoirs would tell me what I had got wrong; but apart from some fresh glimpses of his childhood, there was disappointingly little self-revelation. Now Ziegler, an immensely experienced biographer who has written the official life of Harold Wilson, has given us the official Ted, based on his enormous archive as well as relevant Cabinet papers. His book is characteristically scrupulous, elegantly composed and impeccably judicious. Sadly, however, the mass of material has yielded extraordinarily little by way of new information or insights. Heath remains as impenetrable on paper as he was in life.

He did keep fragments of a diary when young, which reveal a telling mixture of self-confidence and uncertain direction. "I often have the feeling," he wrote in 1940 (aged 24), "that I've a lot of energy, power, ambition and so on, and yet nothing to which to harness it. Is this, I wonder, because I've got so many things I haven't thought out and that, when I've done that, I shall see the way to go." During the war: "I have a desire ... to get 'hard' like other men; to take the knocks they can take, to go wining and whoring with them. Yet whenever I meet them I feel repelled by their lack of intelligence and concern only with things like pay, leave and food. Perhaps my nature's different." Perhaps it was, though there is still absolutely no evidence that he was gay (the one question everybody used to ask when I was writing about him). He was simply asexual. But this youthful introspection dries up once his career gets going.

Ziegler has some touching letters from Kay Raven – the Broadstairs girl-next-door who would have married "Darling Teddy" if he had given her the least encouragement. "You know I'm rather a loving kind of girl and must have been a horrid bore for you," she wrote apologetically when she finally gave up and decided to marry someone else. Typically, Heath regarded her apostasy as a betrayal and made her memory an alibi for never looking at another woman.

The Cabinet papers, littered with impatient marginalia ("Rubbish", "The usual nonsense", "I want action, not cotton wool!") flesh out the received picture of his style of government, confirming how completely he was blown off his intended course. "Do we believe in free enterprise or not?" he demanded, shortly before the famous U-turn in which he poured millions into rescuing industrial lame ducks. He was of course immensely unlucky, having to wrestle simultaneously with soaring unemployment, militant trade unions, the explosion of Northern Ireland and the quadrupling of oil prices – a combination of horrors that might have sunk any government.

But the record vividly conveys the mixture of stubbornness and self-delusion by which the prime minister believed he could fix anything by private meetings with the head of the civil service and a few favoured union bosses. At the same time the Cabinet – including Margaret Thatcher – spinelessly allowed itself to be by-passed without a murmur.

During the long years of his "great sulk", Heath's graceless refusal to grant any merit to his successor commanded a certain respect for his uncompromising integrity. What is surprising is that Ziegler has been unable to paint a more attractive picture of the private man. He still sailed his boats, conducted orchestras and worked hard for the Third World. Yet he emerges as even more selfish, mean, rude and insufferable than ever. Trying to be fair, Ziegler repeatedly insists that he could be a generous friend, good to his staff and an excellent host: but all his anecdotes illustrate the opposite. By the end, ironically, I felt that Heath might have enjoyed his authorised biography even less than he did mine.

With all his faults, Heath changed the course of British history. The tragedy is that even that unquestionable achievement, which no one but the wildest UKIP fanatics seriously wishes to reverse, was soured by his inability to communicate his vision. So that while by sheer determination he succeeded in dragging Britain into Europe, he was never able to persuade either the electorate or his successors fully to embrace it. Instead, much of his own unpopularity transferred itself to the Community, and 40 years later we are still living with that fatal ambivalence.

John Campbell's 'Pistols at Dawn: Two hundred years of political rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown' will be published by Vintage in September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments