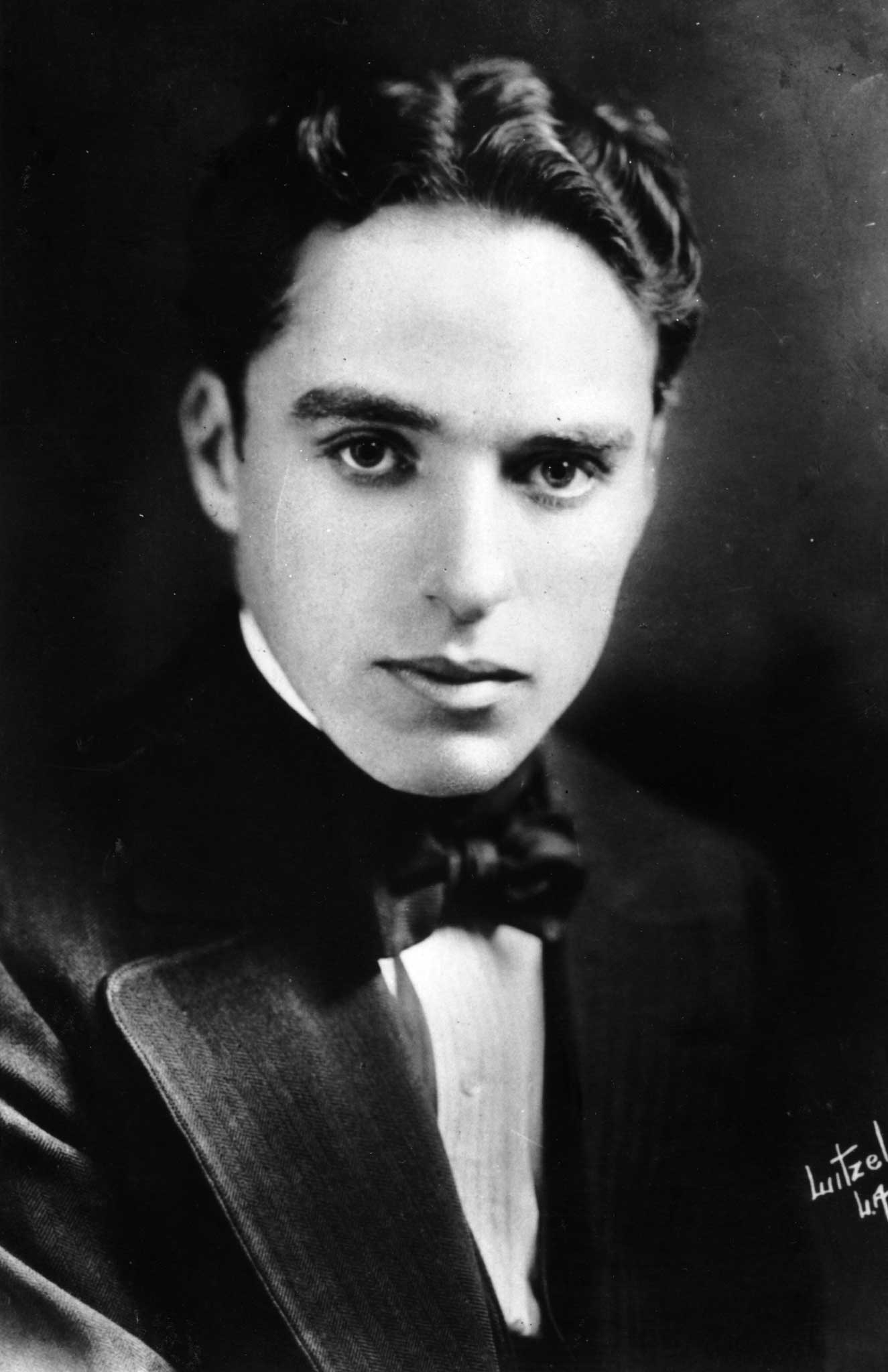

Charlie Chaplin by Peter Ackroyd, book review: An intriguing, if laboured, argument about life and times of a comic genius

When any book on Napoleon, Hitler or Jesus is published (figures with whom the subject of this biography has been compared) the reader might legitimately ask "Why?" Charlie Chaplin has already provided an account of his life, as have several children and ex-wives, and there are nearly 200 biographies in existence, including the definitive Chaplin: His Life and Art by David Robinson. If someone wants to plough such well-furrowed ground, then they either have to discover fresh material or have their own take. In this case, it is the latter. Ackroyd's Charlie Chaplin, is, as one might expect from this biographer, a creation of London, the music hall and late Victorian Britain. He is "Dickens's true successor."

"Chaplin, like Dickens," Ackroyd writes, "was driven, relentless, overwhelming. Both men had always to be in control of the world around them; they had an almost military manner in relationship to their families, and were often accused of being dictatorial and domineering. They seemed to be convivial and gregarious in company but they were invaded by sudden terrors and inexplicable fears; they were both very wealthy men who feared their riches might be stripped away.'

Born in 1889, almost 20 years after Dickens's death, Chaplin was brought up in a south London slum that could have come straight out of one of his favourite novels: Oliver Twist. His absent, alcoholic, music hall father was the inspiration for many of Chaplin's "funny drunk" scenes (A Night Out, One AM, The Cure, Mabel's Married Life); and his mentally fragile mother, Hannah, may have provided the basis for The Kid, filmed in an attic room inspired by Chaplin's childhood lodgings, with Edna Purviance playing a woman "whose only sin is motherhood".

Chaplin's childhood gave him a lifelong hatred of poverty, a distrust of women, and a fear of mental and financial collapse. It energised his ambition, and blinkered his attitude to anything that might stand in his way. From a very young age, he was determined to be a star. Ackroyd traces Chaplin's comic routines back to clog dancing with the Eight Lancashire Lads, the white-faced clowning of Dan Leno, and his work with Casey's Circus and the Fred Karno company. This was physical comedy that Chaplin compared to dance. "Everything I do is dance," he once told Richard Merryman. His new biographer is so excited by this notion that he makes the exaggerated claim: "If all art aspires to the condition of music, as Walter Pater suggested, then all silent film aspires to the condition of ballet." This would be news to DW Griffiths, Georges Méliès, and Erich von Stroheim. Perhaps FW Murnau missed a trick: Nosferatu, the Ballet, has a certain ring.

After tracing Chaplin's rise to become, in 1915, the most famous man in the world (the only person Lenin said he ever wanted to meet) Ackroyd movingly tells of his hero's return to London when he "was not so much delighted at the adulation but frightened and bewildered by it". Chaplin found fame hollow and lonely and was returning home to rediscover "the source of his identity and his being". It is doubtful that he ever found it.

While this concentration on Chaplin as a "Cockney visionary", heir to Dickens and perpetual Londoner, is psychologically helpful, the argument is over-worked. In 1944, no longer as famous or as popular as he once was, suspected of Communist sympathies, and on trial for transporting a young actress across state lines for immoral purposes, Chaplin, Ackroyd tells us, "had deep faith in his own abilities to persevere and to overcome all impediments. That confidence came directly from his troubled childhood."

Possibly. But Chaplin's wilfulness may also have been due to the fact that he was a multi-millionaire and one of the most famous men in the world: better known, as he once observed, than Jesus: a remark that got him into considerably less trouble than it did John Lennon. There are also weird flights of fancy. A paragraph which invites comparison between Chaplin, Napoleon and Jesus ends with the sentence: "Where did Christ end, and Chaplin begin?' The answer is surely that whereas Jesus walked on water, Chaplin would have kept falling in. The tick continues when Ackroyd is so stirred by the comic trope of repeated bottom-kicking in silent comedy that he comes to the conclusion that "all popular comedy from the commedia dell'arte to the contemporary pantomime is homoerotic". Yes, perhaps, Peter, but not all.

There is, however, a refreshing lack of qualm. Early on we are told that Chaplin had a party piece in which he impersonated the orgasms of famous actresses and that he once confessed to having had sexual relations with more than 2,000 women. His biographer adopts a forgiving tone: "That does not seem a very high number for a rich, handsome and famous man." 2,000? Seems quite high to me. We are then given a spectacular anecdote in which Chaplin is so scared of contracting VD that he coats his penis in iodine before confronting Louise Brooks with a colourful erection. A six times a night man, and "hung like a horse", he was perhaps keen to prove that "the little fellow" only applied to his impersonation of a tramp.

The love of anecdote and gossip makes for a pacy read; one so propelled by chronology and concision that the actual films get short shrift. The Gold Rush is given eight pages, City Lights seven pages, Modern Times six. There are no footnotes, so when we are told that Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita may have been inspired by Chaplin's entanglement with Lita Grey (one of several relationships that, in our time, would surely have attracted the interest of Operation Yewtree) we are not told where this comes from (Joyce Milton in The Tramp: the Life of Charles Chaplin).

Perhaps this doesn't matter. Ackroyd brings a novelist's as well as a biographer's eye to the story of a man who "seemed to epitomise the human condition itself, flawed and frail and funny", and is strong on character analysis, contrasting Chaplin the man and the character he played. "As Chaplin became more powerful in life, Charlie became less assertive and more subservient. As Chaplin incurred the wrath of his public for his philandering, Charlie became less libidinous. Chaplin became a millionaire while Charlie was always impoverished. Chaplin was a dedicated and professional film-maker, whereas Charlie could settle down to no employment. Charlie was Chaplin's shadow self."

Fame once attained can seldom be held – unless early death makes it immortal – and Ackroyd understands the loneliness and melancholy at the heart of both fame and humour. There is more to this than the simple cliché of the clown. Tellingly, he quotes Laurence Sterne's observation, "I laugh till I cry, and in some tender moments cry till I laugh". The memory of a desolate childhood may be inescapable, but Charlie Chaplin's final walks away from camera, in films like Police and The Tramp, also show that the secret of comedy, aside from its seriousness, is hope.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies