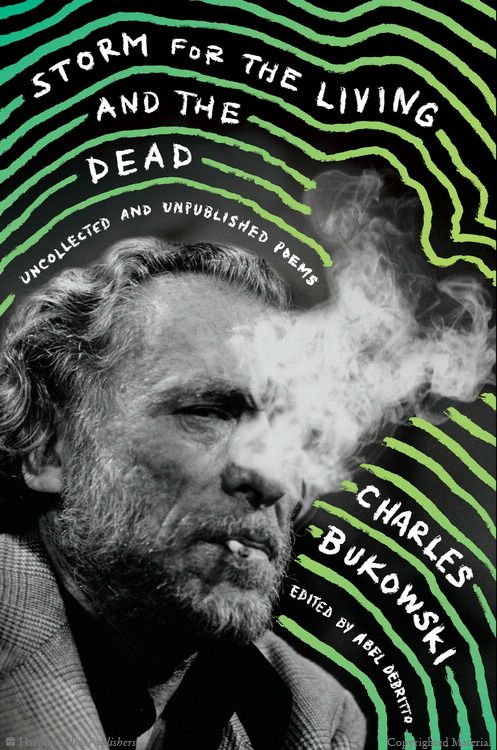

Charles Bukowski, A Storm for the Living and the Dead: Uncollected and Unpublished Poems, book review: There’s gold in this gutter

In this collection we get a full flavour of his preoccupations from gutter-level working-class life to the absurdity of the times, says Alasdair Lees

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Charles Bukowski – the “laureate of American lowlife” – remains a divisive figure more than 20 years after his death. His belligerent and blackly comic novels, stories and poems cast an unsparing eye over the American underbelly and his hard-drinking persona marked him as an ultimate “outlaw” writer. He has been variously denounced as a Nazi sympathiser, an antisemite and a misogynist – a roughneck writer unworthy of serious critical attention.

His prodigious output, at times, to be fair, of variable quality – some 50 to 60 books – is one reason for this critical neglect. Another is the extent to which some of his work – particularly his poetry – has been posthumously disfigured and insensitively cleansed of its pungent vulgarity and profanity.

“Some of the changes are so awful, it’s almost embarrassing,” the editor of this latest collection of Bukowski’s poetry, Abel Debritto, has said. Debritto has previously edited collections of Bukowski’s poetry on subjects from love and writing to cats. He has also penned a useful guide to Bukowski’s career writing for the more than a thousand “littles, mimeos and underground papers”, for which he wrote some 3,000 stories and poems from the 1940s onwards, some of them censored for their content.

Debritto has called this latest collection of poems – many of them written for these obscure journals – the first Bukowski collection in 25 years to “faithfully reproduce” the poems as they were originally written. “This book is the raw, true, genuine Bukowski,” Debritto has said. “There’s the tender Bukowski, the obscene, dirty old man Bukowski, the Bukowski that looks up to other writers, the Bukowski that is in love with women.”

Bukowski expounded his poetic modus – and his view of much modern poetry – in a number of earthy declarations. Poetry, he said, “is a fake product. It’s been fake and dead and inbred for centuries. It’s over -delicate. It’s over precious. It’s a con ... There’s nothing holy about it. It’s a job, like mopping a bar floor.” This anti-elitist ethos is matched in Bukowski’s poetry with a Whitman-esque democracy of subject matter and tone, which seeks to recharge poetry with a free verse communicated with directness and vernacular. Many of his poems, narrative in structure, and usually in the first person, can feel like offcuts from his stories or novels.

In this collection we get a full flavour of his preoccupations – gutter-level working-class life, writers and writing, sex, the absurdity of the times, his readers, a love of the zoo of life and humanity. Some poems, such as the peppery “Tough Luck“ – “I remember this time in the German prison camp / we gotta hold of this queer / they come in handy in times of no women” – seem designed to offend. Others, such as the graphic “Love Song” – “I have swallowed the seed / the fuzz / locked in your legs” – reflect his desire to liberate poetry from what he called “anti-life, anti-truth”. “I would break the boulevards like straws / and put old rattled poets who sip milk / and lift weights / into the drunk tanks from Iowa to San Diego,” runs “Corrections of self, mostly after Whitman”.

And like a latter-day Whitman, in these poems Bukowski ranges over the full panorama of human behaviour, an approach someone can only do justice to by fully immersing themselves in the poems themselves. Far from barrel-scrapings – a charge commonly levelled at Bukowski’s poetry – these are often masterly, and importantly very funny, celebrations of what one critic has called “the aesthetic of the little event”. “Love is wonderful,” he writes in “Warm Water Bubbles”, “but so is the stench of innards / the coming forth of the hidden parts / the fart / the turd / the death of a lung.”

There’s gold in this gutter.

A Storm for the Living and the Dead is published by Ecco, an imprint of Harper Collins, in hardback, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments