Book review: The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls, By Anton DiSclafani

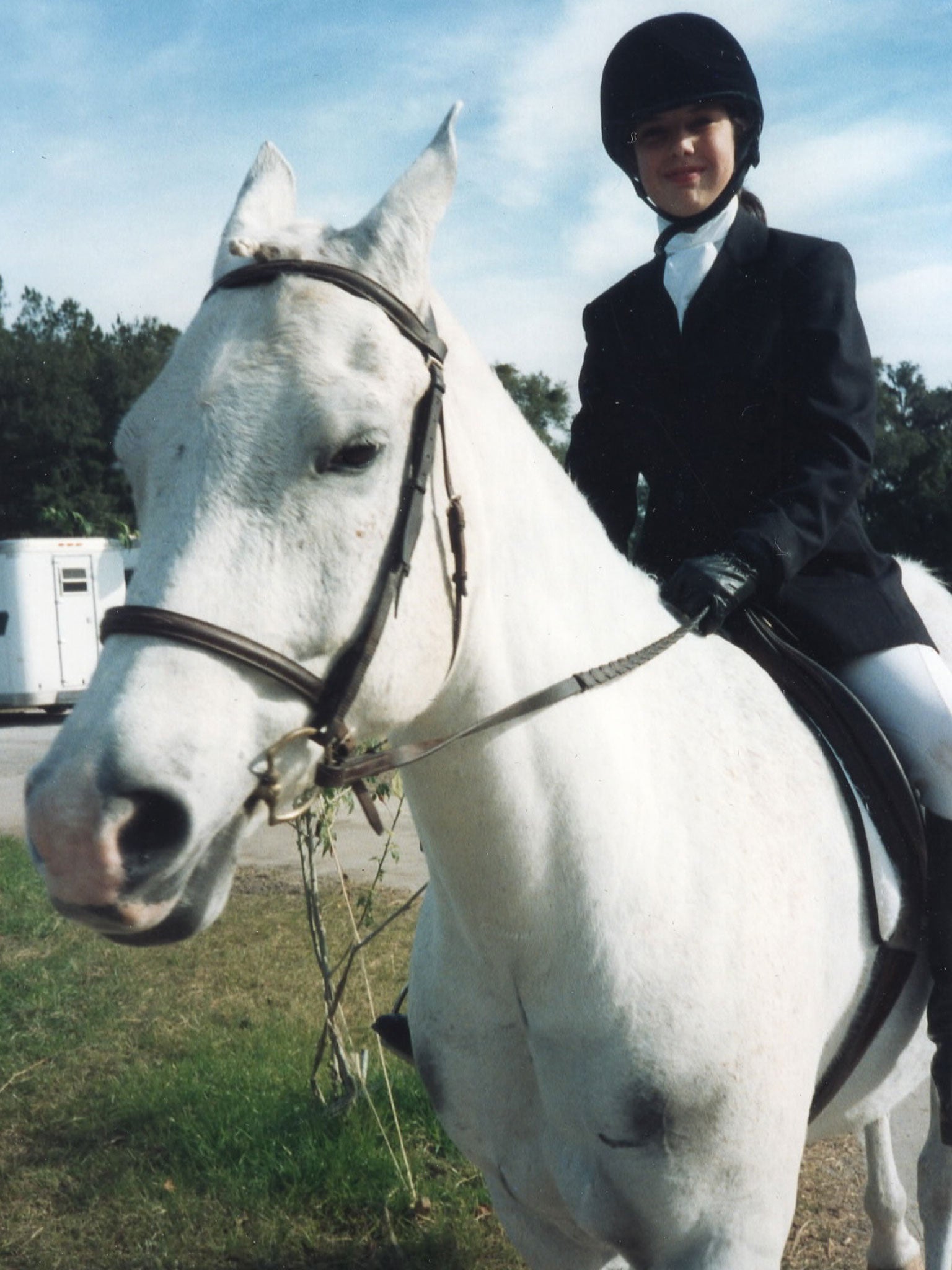

Horses are everything for a Southern teenager sent away to camp after offending her family in this sultry tale set during the Great Depression

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Florida girl Theodora Atwell is 15 when she enrols at Yonahlossee, an exclusive school on a secluded estate nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina. It’s 1930 and the Great Depression is biting. Her father is only a doctor, but the real family money is in citrus. Thea will be mixing with other young ladies from the genteel South, but she is arriving under a black cloud. She has done something to disappoint her parents gravely, something involving her older cousin Georgie and her twin brother Sam, the full details of which slowly unfold in flashbacks.

The title might lead the reader to expect a jolly schoolgirl romp, but this is a sombre coming-of-age novel from a somewhat solipsistic perspective. It’s a long book but what’s striking is what Anton DiSclafani doesn’t put in it. Though Thea develops a strong attraction for the place, Yonahlossee is never vividly described. As a first-person narrator, Thea is somewhat blank and her emotional responses are detached. The other girls are only sketched in – aloof Leona, friendly Sissy, tedious Mary Abbott – and Thea’s deepest relationship is with Naari, the horse she is assigned.

Thea quickly realises that wealth and gentility are relative. “Everyone here seemed so rich and Southern, impervious to the slings and arrows of the world. And then there was me, who had learned to ride from Mother … My middle name was not an important family name, my family did not have five homes stateside, or spend Christmas in Venice.” Despite not coming from the same social echelon as the others, the new girl fits in with remarkably little fuss.

Thea soon finds out that Yonahlossee is not a “camp” in the usual sense of the term, and that she will be there for longer than just the summer. However, DiSclafani hasn’t got much to say about lessons or the day-to-day routine. There is no fetishising of wealth, little detail about the deportment and upper-class etiquette Thea is required to absorb. She is kind to the younger girls and to the servant girl, Docey, and quickly gains the trust of the young and dashing Headmaster, Mr Holmes (if not his wife). He quickly reassures her that, whatever her parents’ intentions, Yonahlossee is not a place of punishment.

Some of the most vivid scenes, appropriately, are those with the horses, with whom Thea has an intuitive rapport. Her approach is never anthropomorphic or sentimental; Naari is just an animal, not a friend. “It would be as if I had died, once my scent disappeared … once she became used to the noises and smells of another girl. But I would always remember my first horse.”

The riding school is the locus of rivalry between Leona, who looks like a centaur on her magnificent horse King, transported from her home in Fort Worth, and Thea on borrowed Naari. Who will win the coveted First Place in the Spring Show? But alongside the innocence of midnight rides and exhilarating trails grows a forbidden entanglement like the one that caused her initial downfall.

Gradually, DiSclafani reveals how profoundly the experience of the Depression will touch every life, even the most gilded. When Jettie, another not very clearly defined girl, is obliged to leave in order to marry a wealthy old man at her family’s insistence, she wails: “I don’t understand. It’s not as if we’re starving. We’re not Appalachians.” Seemingly a place of refuge from the world, Yonahlossee reveals itself as deeply embedded within it, and saturated with sexual tension to boot.

“Money, money where money did not belong, had almost ruined us,” Thea reflects. “I understood that loving, where loving did not belong, would be much worse.” Arriving at Yonahlossee with a sense of stigma, Thea begins to understand more clearly the underlying factors to her behaviour and her family’s reaction to it. “I saw now that it had all started before I was even born. With two brothers, and their sons. A daughter, the odd girl out. And then we were all pressed on by circumstances …. The Miami land boom, which preyed upon my uncle’s hopefulness; the Depression, which amplified my family’s sense of being better than the rest of the world.”

She has been disproportionately punished for her faults, because, as her mother comments off-handedly to Sam, “Thea’s a girl … she doesn’t matter like you do.” Money, class and sexism form a potent, swirling brew. This is a slow-burner, a sultry read which finally delivers a satisfying emotional payoff. Just don’t expect boarding school high jinks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments