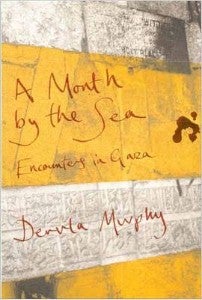

Book of the Week: A Month by the Sea: Encounters in Gaza, By Dervla Murphy

A flawed, partisan portrait of the Israel Palestine conflict that misses an opportunity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is no doubt that Dervla Murphy is a courageous woman when she chooses to be. The subject of her latest book is Gaza, a hostile place for a Palestinian let alone a European woman in her eighties who refuses to cover her head. Repeatedly during her stay in this tragedy of a place, she puts herself directly in the path of danger, whether it is accompanying activists from the International Solidarity Movement as they confront the Israeli army, visiting the tunnels used to smuggle goods and weapons into the Strip from Egypt, or meeting with Hamas hardliners.

Such is the sang froid of this veteran travel writer that she admits to “only one frisson of fear” during her time in the Palestinian territory. This comes when she is travelling away from the town of Khan Younis after visiting the family of a “martyr” of the Qassam Brigades, the armed wing of Hamas. At a busy road junction, Murphy notices a dozen figures dressed entirely in black, including the obligatory terrorist ski-masks, carrying rockets, tripods and AK-47s.

At first she giggles at the sight of these caricature jihadis until one of the men stands immediately beside the minibus in which she is travelling. At this point she becomes terrified, but the cause of her fear is revealing. Murphy is not scared of what an armed jihadi fighter might do with a rocket launcher, even when it is, as she puts it “within cuddling distance”. No, her fear is prompted by the thought that such people are often the target of Israeli drone strikes.

For Murphy, it is never Hamas Islamists nor their even more extreme rivals who terrify her; only Israelis, and in particular “political Zionists”, for whom Murphy reserves a particular hatred.

By far the most disturbing of Murphy’s Gazan encounters is the one with Dr Mahmoud al-Zahar, one of the founders of Hamas. She immediately states that she can detect no anti-Semitism in Dr al-Zahar, despite his peculiar ability to recite the exact dates when Jews were expelled from certain countries or subjected to pogroms. On the other hand, Murphy decides that “our levels of loathing of political Zionism were about equal”. In the pages running up to her meeting with al-Zahar Murphy expresses her deep sense of disquiet with the Hamas charter and its explicit anti-Semitism. But she decides not to raise this with her host. Despite all her courage elsewhere, here it fails her. “It would be hard to mention something so abhorrent without sounding confrontational and accusing - and to what purpose?” she says.

Did Murphy not imagine that this was precisely the line of questioning her readers might have wanted? She has one of the leaders of Hamas in Gaza in front of her and yet refuses to challenge him on the fundamentals. Instead she decides that al-Zahar is a man of such integrity that all other principles and loyalties are thrown aside.

By the time we meet Dr al-Zahar, it is evident that this is not a travel book at all. The genre has a tendency towards self-indulgence, but there is at least a convention that the reader goes on a psychological, spiritual or political journey with the author as he or she is changed by the otherness of the experience of being somewhere else. There is none of that here. This is a travelogue entirely without a journey. Dervla Murphy has decided what she thinks about the Israel-Palestine conflict long before she sets foot in Gaza and everything she experiences merely reinforces her view that Zionism is a colonial disease that lives only to spread its poison.

Her approach undermines even the potentially devastating points she wishes to make about the suffering of the Palestinian people and the human-rights abuses committed by Israel. Murphy visits Zaytoun, the site of a bombing during Operation Cast Lead in January 2009 where Red Cross officials reported that the Israeli army had refused to allow Palestinians to bury their dead or help the wounded until a truce was negotiated. She reports that IDF soldiers sprayed graffiti on the homes: “ARABS NEED 2 DIE – DIE YOU ALL – 1 IS DOWN, 999,999 TO GO – ARABS 1948-2009”.

Such testimony should be a challenge to those who would wish to represent Israel as an oasis of democracy and civilised Western values surrounded by a murderous desert of Islamist anti-Semitism. This is certainly Murphy’s intention. But by the time we join her at Zaytoun, she has become an unreliable witness. It is quite possible to write about Gaza without descending into pat language about Zionist imperialism. Gideon Levy’s The Punishment of Gaza, or Footnotes in Gaza, Joe Sacco’s graphic novel, challenge the Zionist narrative while demonstrating a genuine empathy for Israel. Indeed, Levy’s book argues that the situation in Gaza is a profound wound on Israel as much as it is a catastrophe for the Palestinians. It is disturbing for supporters of Israel but it is never glib.

A Month by the Sea is a disturbing book for all the wrong reasons. Occasionally there are glimpses of another story – the story of women under Hamas rule – that Murphy would be perfectly placed to tell. At one point, she quotes a report from the Palestinian Working Woman Society for Development which concludes: “The practice of violence against women in the Gaza Strip is based on man’s belief that violence is the suitable tool to control women’s behaviour.” She notes this and then chooses to look away, presumably because this is one aspect of Palestinian suffering that can’t be blamed on Israel.

Martin Bright is the former political editor of the Jewish Chronicle

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments