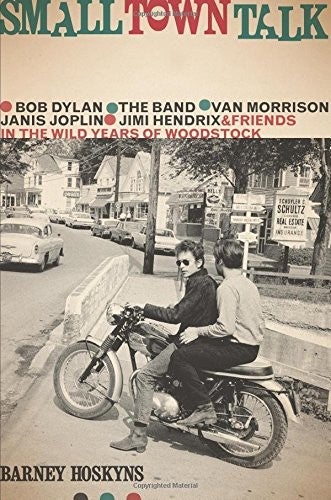

Barney Hoskyns, Small Town Talk: 'Woodstock – where stardust wasn’t always golden', book review

In Small Town Talk, he shifts his focus to East Coast USA, specifically Woodstock, the town 100 miles north of New York on the edge of the Catskills

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Popular music has scores of sacred spaces, the geographical locations that have yielded era-defining scenes or provided the backdrop to rock’n’roll psychodrama.

The music writer Barney Hoskyns has visited a fair few of them over the years, lingering in Laurel Canyon for his 2006 book Hotel California.

In the similarly terrific Small Town Talk, he shifts his focus to East Coast USA, specifically Woodstock, the town 100 miles north of New York on the edge of the Catskills, and what he calls a “staging post between Greenwich Village and the Great American Wilderness”.

But those groaning at the prospect of another book about the Woodstock festival can breathe easy. Hoskyns’ focus here is on the town and the creative communities that sprang up around it, and they are vividly drawn.

It was here that Bob Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman and his wife, Sally, pitched up in the early Sixties and bought an estate that had belonged to the illustrator John Striebel, and where Dylan himself arrived not long after.

Such was this tiny town’s hip status that when the Brooklyn promoter Michael Lang had to move his festival 60 miles from the planned site, he opted to retain the name.

Where Dylan went, scores of hippies and hangers-on followed and a new scene materialised, giving rise to the dope-smoking, garland-wearing, counter-cultural stereotype that’s now been mythologised.

As the Grossman and Dylan families dug in, a starry roster of musicians came calling, among them Robbie Robertson, Van Morrison, Tim Hardin, Karen Dalton, George Harrison, James Taylor and John and Beverley Martyn, each lured by the notion of a secluded bucolic idyll.

Hoskyns himself lived there for four years in the Nineties, and his affection is clear.

He has, he says, put down roots “that have never quite been torn out ... I believe in the spirit of the place, a psycho-geography that may be little more than kind of romanticism but that enshrines something good about the people who’ve lived there”.

That “something good” is freedom and creativity, an ethos that dates back to the late 19th century when Woodstock formed the base of a rural arts colony inspired by the French Impressionists and the British Arts and Crafts Movement.

But with the Sixties folk-rock luminaries came the drugs, the wastrels and the no-hopers. In what was his first family home, Dylan would find disciples sleeping in the bushes and hanging out around his pool.

As Dylan’s fame grew so did his neurosis, and Hoskyns paints a queasily detailed picture of the singer’s troubles, notably the tension between country and city, acoustic and electric, monogamy and infidelity, staying straight or getting wasted.

Indeed, when it comes to the majority of the scene’s big players, creative tensions, drug-induced paranoia and financial fallings out are rife.

While Dylan takes up much of the narrative, Grossman is the man who binds the stories together and essentially the foundation on which the scene was built. He is a resourceful, powerful, vain and greedy figure who discovered the folk-pop trio Peter, Paul and Mary, and steered the careers of The Band, Richie Havens, Todd Rundgren and Janis Joplin. Yet, in the end, he just wanted to stay at home and tend to his tomatoes.

His instincts were indisputable though, even if they appeared risky at the outset. His signing up of Dylan was a gamble, given that he was an artist who “sang in an astringent voice, strummed his guitar in the most rudimentary manner, punctuated his Guthrie-esque phrasing with weedy harmonica phrases and could not be described as good-looking.”

There are several of these witty asides where Hoskyns’ inner critic bobs to the surface; you couldn’t accuse him of having a rose-tinted view. Mostly, though, this is a meticulous historical account in which he keeps his distance, allowing others to do the talking. Indeed the sheer volume of interviewees is dizzying, and testament to the author’s methodical approach.

He is also careful to underline the musical legacy of this modest town, most lastingly in the Americana movement.

Bringing his reflections up to the present day are his conversations with contemporary artists still enamoured with the place, among them Mercury Rev’s Jonathan Donahue and Simone Felice of the Felice Brothers, the sibling outfit whose carpenter father came to the Catskills for the Woodstock festival and never left.

Most of all Small Town Talk captures the atmosphere and the spirit of a town where, according to Dylan’s sometime guitarist Larry Campbell, “you can just be who you are”.

It’s a place that, for a culturally fertile period, filled up with talented yet troubled souls all looking for inspiration and escape, and found that wherever you go you still have to take yourself with you.

Small Town Talk, by Barney Hoskyns. Faber £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments