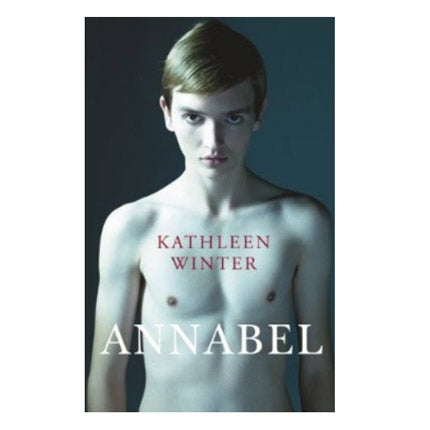

Annabel, By Kathleen Winter

A debut novelist takes on the difficult subject of hermaphroditism in a lyrical story set among hardy people in a 1960s Canadian settlement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a brave debut novelist who tackles the subject of human hermaphroditism, not only because the condition is exceptionally rare ("pseudo-hermaphroditism", where only the outer organs look ambiguous, is more common), but because similar themes have been touched on by such accomplished authors.

Rose Tremain wrote of gender dysphoria in Sacred Country, and Jeffrey Eugenides's Middlesex was centred on intersex. But Kathleen Winter has the steadfast clarity and quietly assured talent to make this difficult subject her own, and Annabel was listed for the Giller and the Rogers prizes and the Governor General's Literature Award in her native Canada, before being listed for the Orange prize, here.

In the bleak, sparse landscape of an insular settlement in Canada in 1968, where men are men (hunting, trapping) and women stay at home, a baby is born to Jacinta and Treadway. Only they and their discreet neighbour, Thomasina, know a secret about the child: it possesses both male and female genitalia.

Doctors decide that the child should be brought up as a boy, and Wayne undergoes surgery and regular hormone treatments. But he doesn't feel like a boy. Treadway, an archetypal silent, reliable man, tries to interest his son in male pursuits, but Wayne is more attracted to female ones: he is fascinated by synchronised swimming and wants to wear a sparkly swimsuit; he persuades Treadway to help him build a bridge den, but then dismays him by filling it with soft furnishings. Jacinta aches to embrace the daughter she feels is repressed in her child, but society would never accept it. "Human life came second to the life of the big land, and no one seemed to mind. No one minded being an extra in the land's story."

Throughout Wayne's childhood, Thomasina sends him postcards of bridges from around the world. These bridges are a metaphor for the communication between Wayne's male and female sides.

In writing as stark and pared-down as the desolate landscape, Winter tells the tale of a child growing up feeling as if (s)he is living a lie. The frozen landscape is a metaphor for emotions trapped by ice.

Most of the descriptive prose is melodically poetic, marrying spare lucidity and sage observation. Here is Winter on the proscribed roles for men and women: "The unendurable winters were all about hauling wood and saving every last piece of marrow and longing for the intimacy they imagined would exist when their husbands came home, all the while knowing the intimacy would always be imaginary ... Then came brief blasts of summer ... desire and fruition and death all in one ravenous gulp, and the women did not jump in. They waited for the moment of summer to ... expand enough to contain women's lives, and it never did." Even mundane tasks are illuminated by harmonious language: boiled partridgeberries emit a "bloody, mossy tang that smells and tastes more of regret than of sweetness".

Winter's flair for capturing atmosphere is not confined to the harsh land and its inhabitants' arduous labour. She is equally adept at using her idiosyncratic eye to create charming images. Jacinta recalls visiting the cathedral in her home town as a small child: "Easter lilies, whose perfume mingled with the shade and atmosphere of the great stone walls to create a chalice in which each child sat in wonder like a small, bright, plump bee sucking mysterious nectar, intoxicating and unnerving and powerful."

As the story progresses through Wayne's childhood, there is so much to cram in – even with the book's hefty 462 pages – that the narration sometimes jumps from majestic to utilitarian. ("After the lettuce sandwich, Wayne and Wally became friends.") The volume of material may also explain why significant events are related with undue haste. For a novel so emotionally intelligent, a friendship broken or a life-changing injury deserves more space. But Winter maintains high standards, emulating the accessible populism of accomplished epic writers such as Wally Lamb.

Flaws are few. A medical emergency that arises is not physiologically possible, and adds a tabloid tang. A couple of incidents feel implausibly convenient – Thomasina names her hotel on a postcard just when it's needed; Wayne, broke and on a walk, finds a man needing a delivery boy; Wayne saving a life without fanfare; hobos who read Dostoyevsky. Some of the characters fall into the James Frey trap of being angels or devils – a vile schoolgirl; a paedophile teacher who is also a grass. But other characters are complex – Wayne's dangerously loquacious but kind-hearted young friend; a didactic head who shows her softer side.

These reservations are minor. Winter has a strikingly mellifluous voice, and she has created a potent story exploring gender categorisation and humanity.

To order any of these books at a reduced price, including free UK p&p, call Independent Books Direct on 08700 798 897 or visit independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments