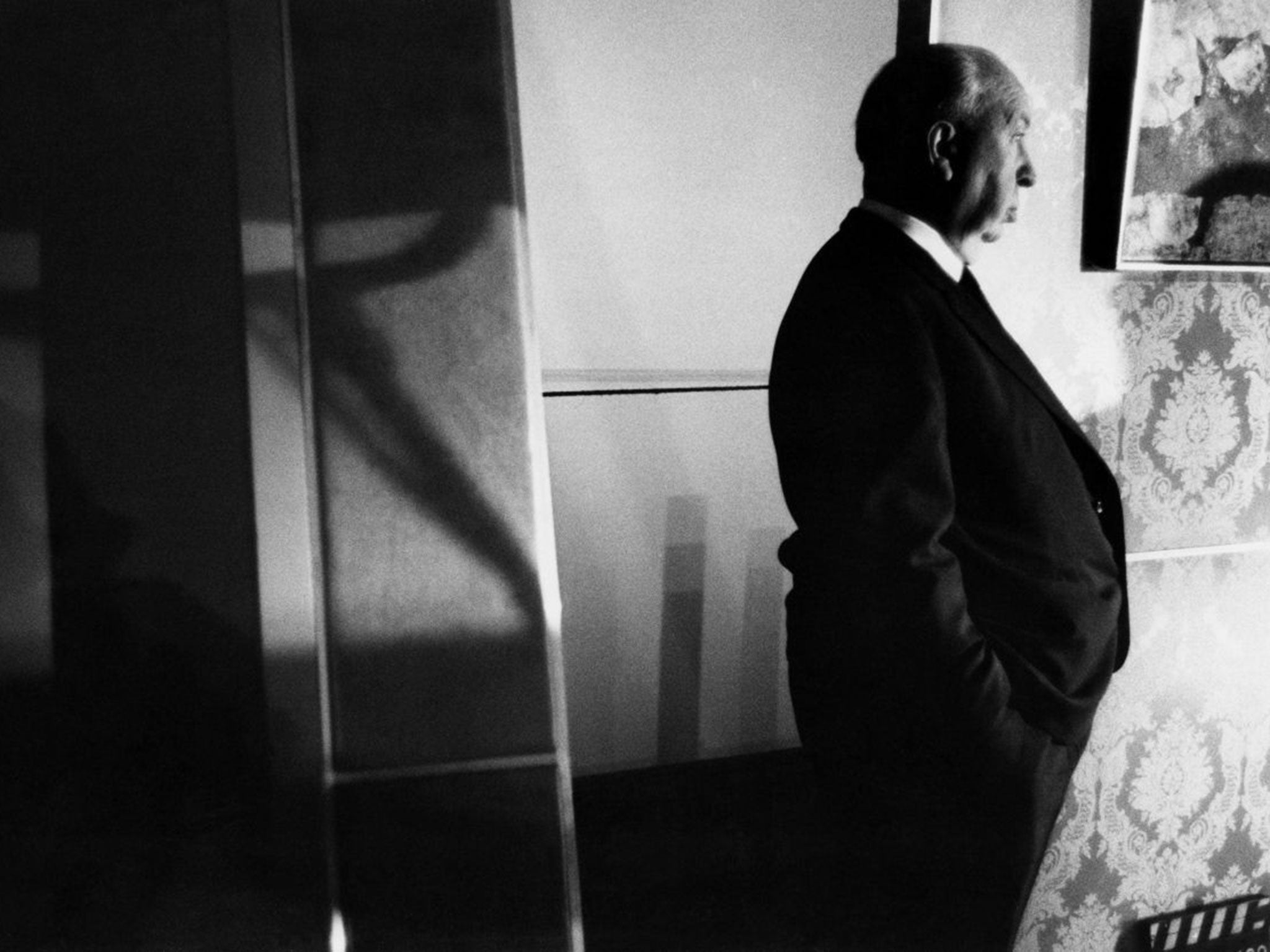

Alfred Hitchcock by Peter Ackroyd, book review

Prolific writer Peter Ackroyd has summed up frightmeister Alfred Hitchcock's life in only 259 pages. Louise Jury is left wanting more

The appeal of Alfred Hitchcock to Peter Ackroyd is not hard to imagine, coming hot on the heels of his life of Charlie Chaplin and with the whole sweep of his historical understanding of London to draw on.

The director whose biggest hits – Psycho, Rear Window, The Birds, Vertigo, North by Northwest and more – are now acknowledged classics was born in the capital and forged his early career with British movie pioneers such as Michael Balcon at Islington Studios. Since his death at the age of 80 in 1980, his reputation has only risen, as is reflected in the long list of 100 previous publications Ackroyd readily acknowledges.

This swift new survey models itself on the director’s own straightforward pragmatism, starting at the beginning and forging onwards to death using the chronology of the movies. Of central importance is Alma Reville, already a talented doyenne of the cutting-room floor and young assistant director when they meet, whom he marries in 1926. She appears an integral part of his success and the person he cannot live without, even as Ackroyd highlights a certain asexual quality to their relationship.

Alma aside, the plot of Hitchcock as rendered by Ackroyd rests on a handful of key ideas – fear, obsessiveness, and less his fascination with the so-called Hitchcock blonde than his penchant for strong women who shared his fondness for dirty jokes. Fear is a constant refrain. Hitchcock himself described how the black-robed Jesuits of his Catholic education instilled a nervous terror with their harsh, rubber-strap discipline. “I was terrified of the police, of the Jesuit fathers, of physical punishment, of a lot of things. This is the root of my work.” That the great director was more than capable of editing his own life stories for maximum effect is emphasised by Ackroyd elsewhere, though he seems to accept this statement at face value. “He had such an intimate connection with his own anxieties that he was able instinctively to stir those of the public,” Ackroyd says.

Of course, it is manifestly the case that Hitchcock forged a career on scaring his audiences. And there also seems considerable evidence that he was willing to terrify – and at the very least disquiet – his stars if that would produce the required performance. Tippi Hedren, star of The Birds and Marnie, was not alone in being bullied.

But in the hands of Hitchcock, this technique seems less Method than common-sense tactics, like other aspects of his art. Although he downplayed the involvement of his collaborators to offer an auteur-like vision of himself and his work to the public, he also emphasised the commercial rather than the artistic nature of his job. When his granddaughter enrolled at film school, Ackroyd tells us that Hitchcock proved pretty useless at helping her with essays on his work because he had such little truck with the required academic art-house theorising.

Yet some of the more interesting parts of his story are his encounters with European art house. As early as 1924, he and Alma were dispatched to learn from the flourishing German film industry where the great FW Murnau, who had already

directed Nosferatu, was working next door. “From Murnau I learned how to tell a story without words,” Hitchcock said later. He learned camera techniques, too, and the frightening chiaroscuro effects of darkness and light. And it was not his only link to a bigger tradition of European cinema. For many years he was in close contact with the director François Truffaut, and the French were admirers long before the British cognoscenti united to affirm Hitchcock’s greatness.

To any cinephile, some of the details in this volume are irresistible. Hitchcock often filmed box-office hits in the kind of time frame today regarded as low-budget indie timetabling, with The Lady Vanishes wrapped in Islington in five weeks. By the time he set sail for Hollywood on March 1, 1939, he had made 24 films in 13 years.

Ackroyd flags the sad what-ifs of collaborations that never happened as the likes of Ernest Hemingway declined overtures. But there’s all the fun of stars such as Grace Kelly who, we are assured, slept with her leading men. And the sources of inspiration can be intriguing. North by Northwest, Ackroyd tells us, began with Hitchcock observing: “I always wanted to do a chase against the faces of Mount Rushmore.” Then there is the director’s capacity to identify an unlikely detail and make it crucial, as in the shower scene in Psycho that was nowhere near as prominent in the original book.

Yet while no life of Hitchcock can be entirely dull, it is hard not to conclude that Ackroyd on Hitchcock was something of a quick-fire exercise in précis. When Ackroyd is on top form, a Peter précis might be preferable to many a writer’s more assiduous investigations. But he may have been too cursory here.

For all the felicitous phrasing, a sneaking suspicion of a book written in haste remains. From the conjuring of the streets of Leytonstone and Limehouse in his childhood or on the set of The Birds, there are other moments which are, quite simply, ridiculous. In only the second paragraph, he describes William Hitchcock, Alfred’s father, a greengrocer, “selling everything from cabbages to turnips”. As opposed to a greengrocer selling, well, what exactly? A distinctive vocabulary is less impressive when a word such as “threnody” appears twice in three pages.

For all the cavils, there will be many a reader more than happy for an insight into the life of a cinematic great in 259 pages against more than 800 required for Ackroyd’s imaginative, freewheeling history of London (completion of which preceded a heart attack) or his monumental 1,195-page tome on Charles Dickens a quarter-century ago. Yet his Dickens was hailed as “likely to remain definitive for years to come”. I fear his Alfred Hitchcock will not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments