Shakespeare’s handwriting to be digitised by British Library for first time - and his words defend refugees

The collaboratively written play ‘Sir Thomas More’ is the only surviving manuscript to contain the Bard’s handwriting

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The pages of the only surviving manuscript to contain Shakespeare’s handwriting are to be digitised by the British Library, where the public will be able to view an impassioned speech in defence of refugees in London.

It is part of the digitisation of more than 300 manuscripts, books, maps, paintings, illustrations and more that will be available on the British Library’s new Discovering Literature: Shakespeare website.

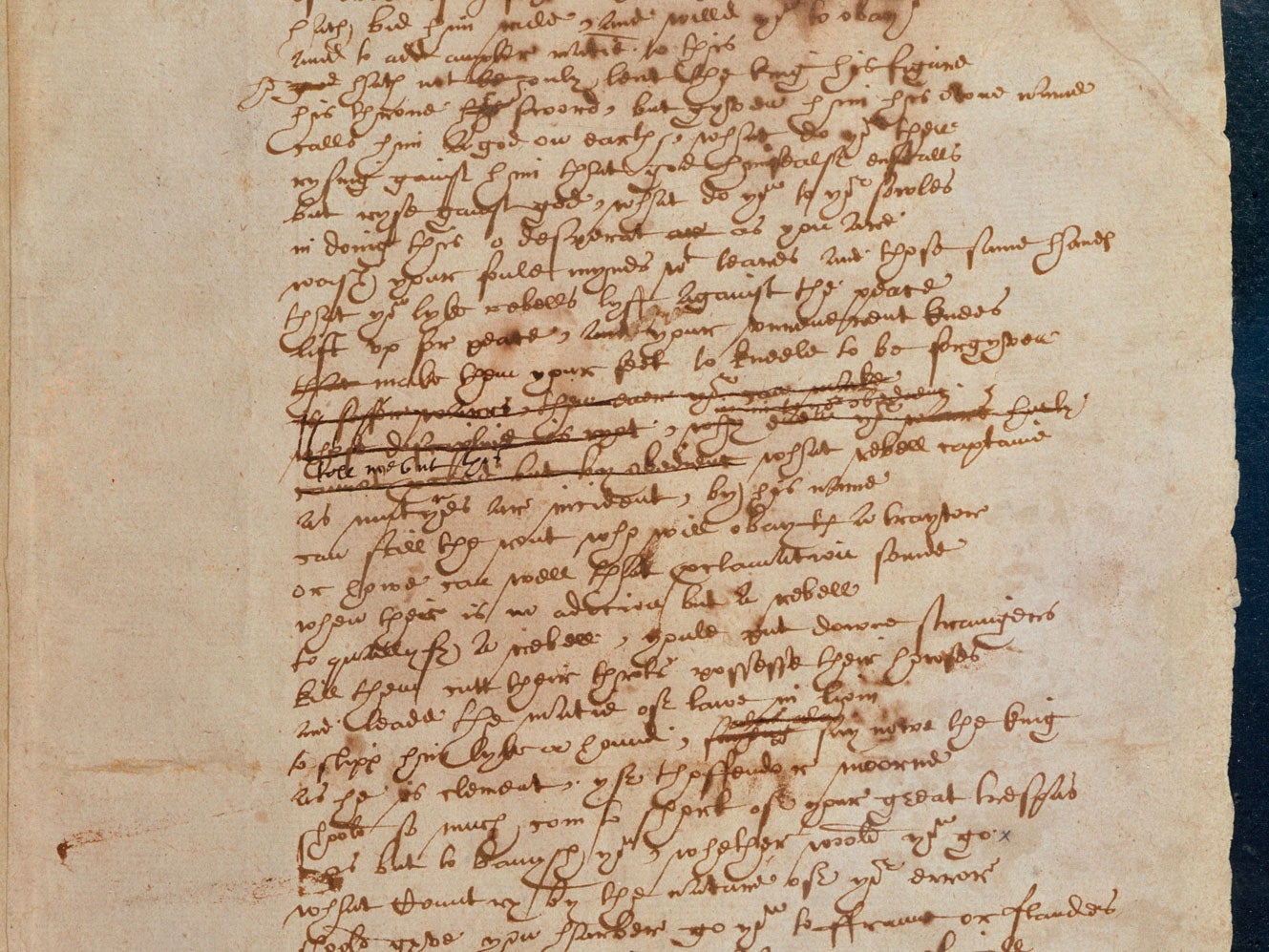

The British Library has identified Shakespeare’s hand in the pages of the play ‘Sir Thomas More’ through the writing itself and the spelling, vocabulary, the imagery used and the ideas he expresses in the text.

‘Sir Thomas More’ focuses on Henry VIII’s chancellor and was originally penned by Anthony Munday between 1596 and 1601. Shakespeare had been commissioned to write just one scene but was later involved in revising the script alongside other playwrights including Henry Chettle and Thomas Dekker.

Shakespeare’s scene sees Sir Thomas More defend French refugees who are about to come under attack from an angry mob. He says:

You’ll put down strangers, Kill them, cut their throats, possess their houses,

And lead the majesty of law in lyam

To slip him like a hound.

Alas, alas! Say now the King

As he is clement if th’offender mourn,

Should so much come too short of your great trespass

As but to banish you: whither would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbour?

Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, Spain or Portugal,

Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England:

Why, you must needs be strangers.

Critic Jonathan Bate told the British Library that in this scene, “More asks the on-stage crowd, and by extension the theatre audience, to imagine what it would be like to be an asylum seeker undergoing forced repatriation.”

More than 500 English teachers in the UK have revealed that over half of students find it difficult to relate to or understand the Bard’s plays. The Discovering Literature site is designed to help people discover the culture, politics and society of when Shakespeare wrote his plays, and to better understand the plays themselves.

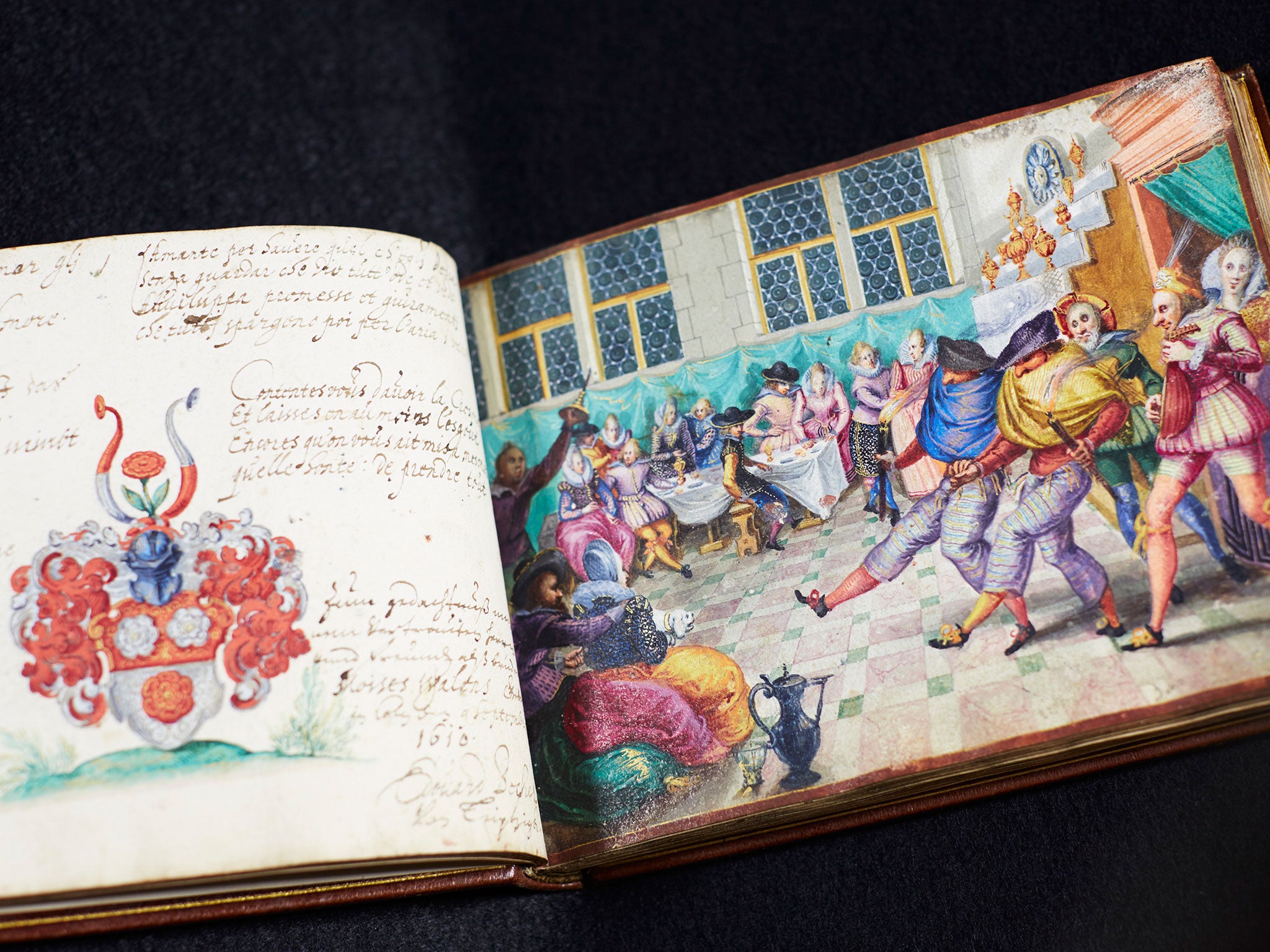

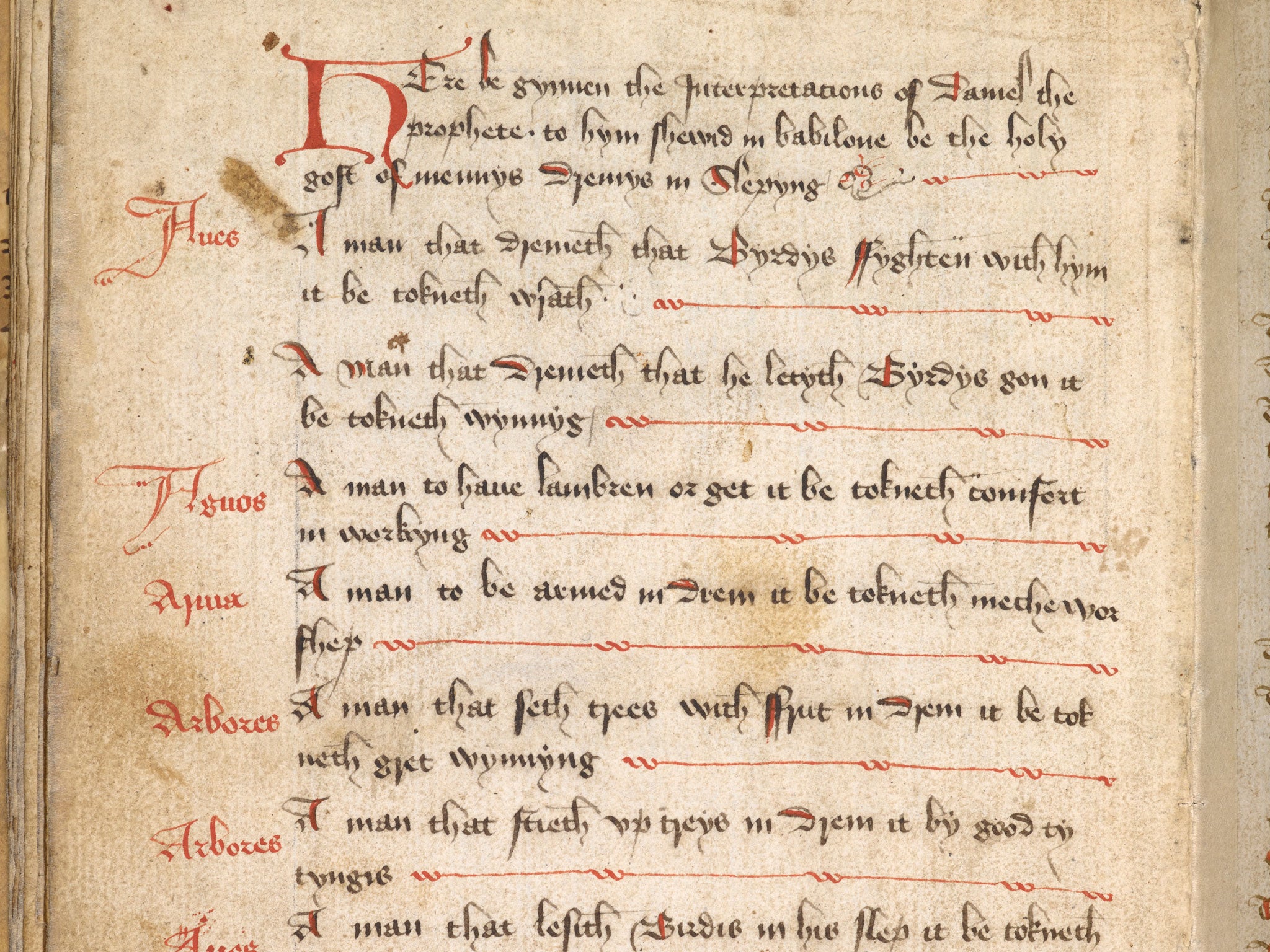

The dedicated site will also hold a 17th century manuscript thought to hold the original tune of one of the Fool’s songs from King Lear; Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s personal annotated copy of ‘The Dramatic Works of Shakespeare’, and the only surviving portrait of John Dee, the Elizabethan scholar thought to have inspired the character of Prospero in The Tempest.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments