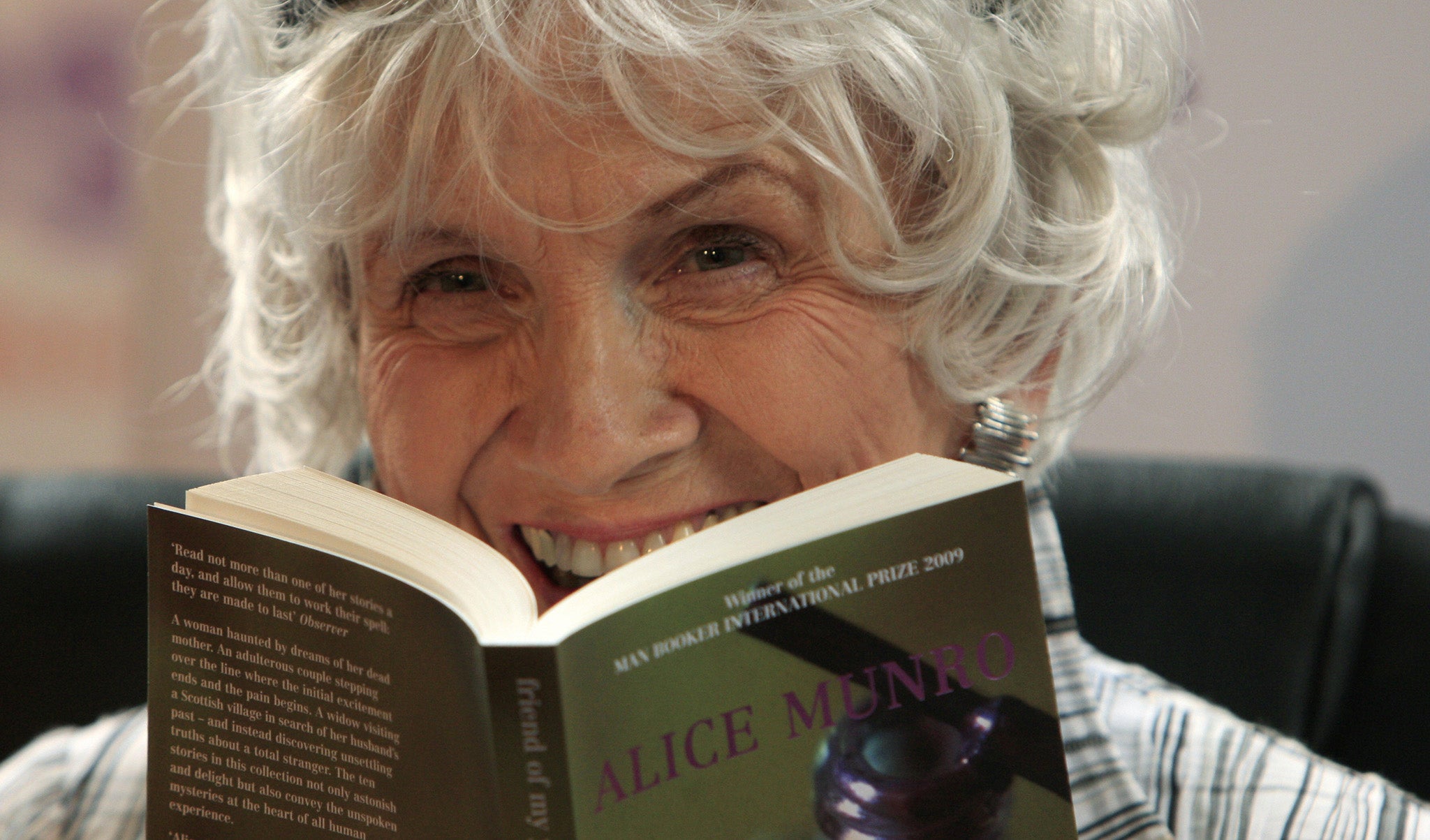

'I never thought I would win': Alice Munro awarded 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature

Canadian author described as the 'master of the contemporary short story'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hailing the 13th woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature with a gender-blind turn of phrase, the Swedish Academy today praised Canadian author Alice Munro as a "master of the contemporary short story".

Speculation over the past few days had seen foes of the Academy sharpening their knives for a routine assault on the secretive institution as a friend of (to them) obscure and unread writers. Romanian novelist Mircea Cartarescu, Norwegian dramatist Jon Fosse and - most recently - Russian documentary writer Svetlana Alexievich had all surfaced as favourites.

In the event, the Academy kept up its reputation for surprise by picking a globally acclaimed, popular and accessible English-language writer - as it has since the millennium when bestowing the prize (worth eight million Swedish krona or £770,000) on Doris Lessing, VS Naipaul or Harold Pinter.

"I knew I was in the running, yes, but I never thought I would win," said Munro when contacted by The Canadian Press.

Born Alice Laidlaw to a hard-pressed farming family of Scottish and Irish origins in rural Huron County, Ontario, in 1931, Munro studied at the University of Western Ontario. She married James Munro, later a bookseller, while still a student and did not complete a degree. The couple had four daughters but divorced in 1976; she married her second husband, geographer Gerald Fremlin, in 1977.

Munro published her first collection of stories - Dance of the Happy Shades - in 1968 and her 14th, Dear Life, in 2012. Over those 45 years, the "Canadian Chekhov" has won both critical reverence and the loyalty of fans across the world for stories that can encapsulate a life within a dozen pages, and for a tender but unsparing gaze on the ordinary events that assume giant dimensions in all our lives.

She underwent heart surgery in 2001 but the new millennium ushered in some of her boldest and frankest work, in collections such as Runaway and Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage. In 2009, she won the biennial Man Booker International Prize for career-long achievement.

After her husband's death this April, she announced that Dear Life would be her final book. In response, American novelist Jane Smiley wrote: "Thank you for your unembarrassed woman's perspective on the lives of girls and women, but also the lives of boys and men. Thank you for your cruelty as well as your kindness, because the one plus the other is the essence of truthfulness."

Fellow Canadian Margaret Atwood, who acknowledges Munro as a shame-busting, truth-telling pioneer, has stressed the broad life-spanning perspective in her tales: "She writes about the difficulties faced by people who are bigger or smaller than they are expected to be. When her protagonists look back… the older people they have become possess within them all of the people that they have been. She's very good on what people expect, and then on the letdown."

Her Nobel accolade counts as a victory for women authors, for Canadian literature and for the often-marginalised art of the short story. Not since Isaac Bashevis Singer in 1978 - another author who began with the narrow horizons of life in small communities and lent them a universal resonance - has a figure best known for short fiction taken the prize.

Munro has written that, "What I wanted was every last thing, every layer of speech and thought, stroke of light on bark or walls, every smell, pothole, pain, crack, delusion, held still and held together – radiant, everlasting."

Now the world's most solemn literary honour has gone to a modest, immaculate but far-sighted miniaturist. That ringing endorsement of a viewpoint and an art-form that more pompous literati might brand as "domestic" will, for some, be a shockingly radical gesture in itself. Never write off the Nobel.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments