Yann Martel on the genius of Elizabeth Smart: Author's great novel has been republished

Here, the Booker-winning author celebrates Smart's 'By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept' - a tale of wasted passion for a wayward poet

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At one point in this beautifully sad book, Elizabeth Smart says of herself, "I am more vulnerable than the princess for whom seven mattresses could not conceal the pea." The more appropriate fairy tale for the sake of comparison would be Sleeping Beauty, because 'By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept' is the story of a woman who was asleep for 100 years until the kiss of a man (more precisely his poetry) woke her up to life and to love. Smart's evocation of love is sweeping, aching, exhilarating, rapturous, incantatory: "When the Ford rattles up to the door, five minutes (five years) late, and he walks across the lawn under the pepper-trees, I stand behind the gauze curtains, unable to move to meet him, or to speak, as I turn to liquid to invade his every orifice when he opens the door. More single-purposed than the new bird, all mouth with his one want, I close my eyes and tremble, anticipating touch."

And again: "What is going to happen? Nothing. For everything has happened. All time is now, and time can do no better. Nothing can ever be more now than now, and before this nothing was. There are no minor facts in life, there is only the one tremendous one."

I know, I know, this is merely the introduction and not the book itself, but one more: "The surety of my love is not dismayed by any eventuality which prudence or pity can conjure up, and in the end all that we can do is to sit at the table over which our hands cross, listening to tunes from the Wurlitzer, with love huge and simple between us, and nothing more to be said."

In this high-wire act of sustained emotional resonance, the following might help anchor the reader in the great wash of language: in August of 1937 in London, Elizabeth Smart, from Ottawa, Canada, came upon a book of poems in a bookshop on Charing Cross Road, and, so the story goes, fell in love with its author, George Barker. But simply loving his words would not do; she wanted to love the man himself.

For that, she would need to meet him. Orchestrating that encounter would take three years, requiring various wiles (pretending to be a manuscripts collector) and some cash (she was from a wealthy family that more or less supported her). At last, in 1940, after bringing him over all the way from Japan, where he was unhappily teaching, they met in California, where she was living in an artists' colony in Big Sur. They first set eyes on each other at a bus stop in Monterey – that's how the book starts – and they soon became lovers. They would have four children.

Problems soon arose. They were arrested under the Mann Act for travelling with an immoral purpose when they tried to cross a state border. Smart laments: "They are taking me away in a police car. The policeman's wife sits stiffly in the front seat. They are prosecuting me for silence and for love."

She asks one of the police officers who arrests her: "What do you live for then?

"'I don't go for that sort of thing,' the officer said, 'I'm a family man, I belong to the Rotary Club'."

In discussing that sort of thing, Smart makes a number of Biblical references, most obviously with the title, that marvellous amalgam of a New York train station and the ache of Jewish exile, but her more frequent allusions are pre-Christian. "Jupiter has been with Leda, I thought, and now nothing can avert the Trojan Wars" is one example. She also refers to the Golden Fleece, to Helen of Troy, to Diogenes, to Penelope, to Dido. There is indeed something of an ancient Greek sensibility to this book, in which the morality of behaviour comes second to its emotional import. I feel, therefore I am – and with a truth of being that no moral code can affect. By Grand Central Station came out in 1945, and we all know what happened between 1939 and 1945. Smart was not ignorant or unfeeling – she makes heartfelt references to the victims of the Holocaust, for example – but as she puts it: "Why should even ten centuries of the world's woe lessen the fact that I love? Cradle the seed, cradle the seed, even in the volcano's mouth. I am the last pregnant woman in a desolated world. The bed is cold and jealousy is cruel as the grave."

Was she self-centered, solipsistic, detached from reality? Not at all. She demanded bliss, while accepting that she might end up in hell. "The Thing is at hand. There is nothing to do but crouch and receive God's wrath," she says. And wrath was to come, not only from police authorities and other representatives of the harsh world at large, but closer at hand, because George Barker was married – he flew over from Japan with his wife, Jessica, whom Smart also sets eyes on for the first time in Monterey – and he would have durable relations with more women than just his first wife and Elizabeth Smart, and more children than just the four he had with her (15 in all!).

Here's the point in comparing Elizabeth Smart's art with her life, and the proof that this jewel of a book is no mere idle romance: Elizabeth fell in love with George, it took time, tricks and money to meet him, they got into trouble with the law, they became social outcasts, it was killing for her heart – and she had four children with the man, children whom she raised all on her own. This is a woman who took seriously not only the premise of love, but its consequences. This is a book about one creature's obdurate desire to love and be loved, no matter what. Smart was lucid, resilient, hard-working, and responsible in her love-madness.

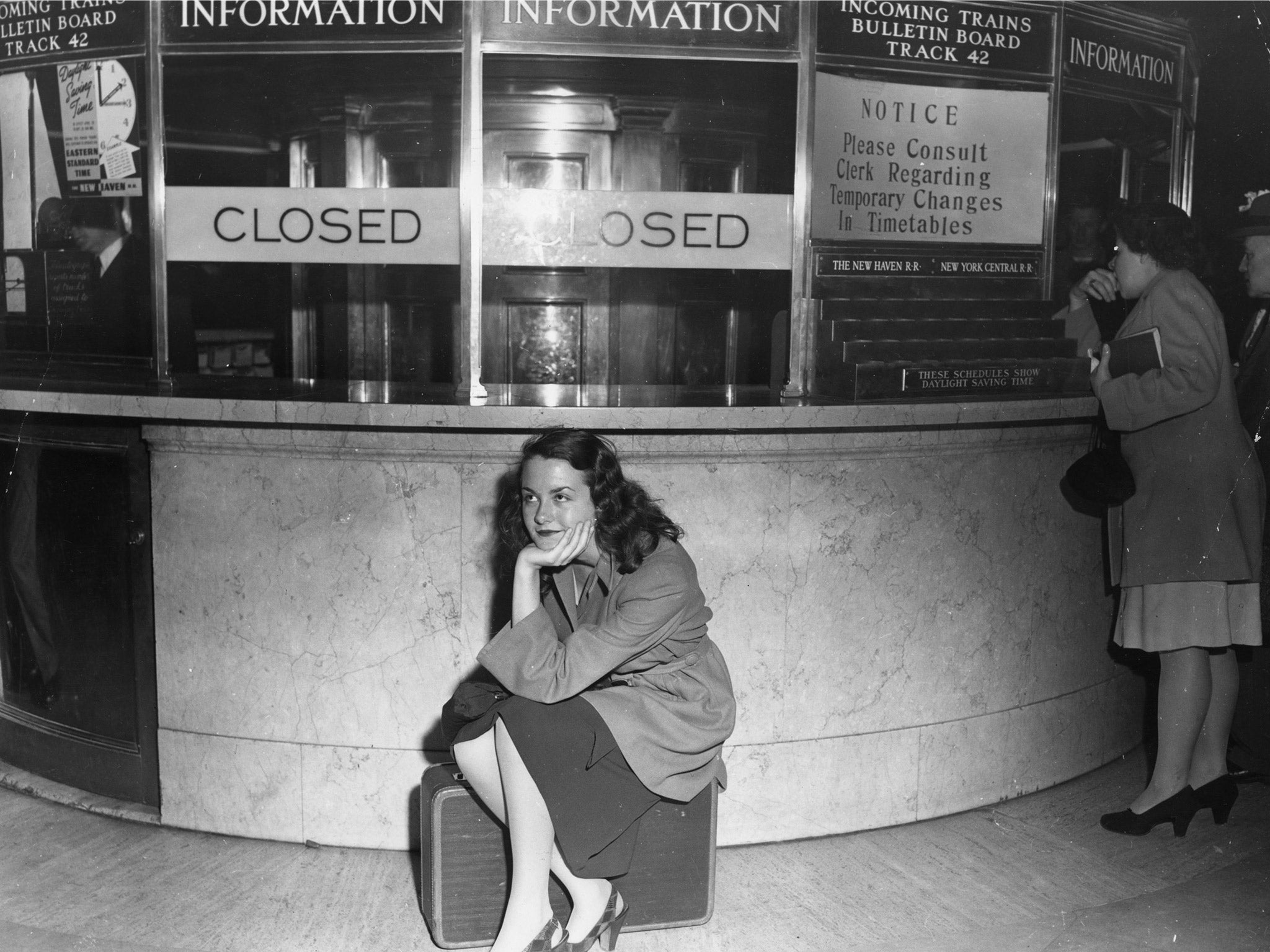

The photo at the back of the edition I have, published during the author's lifetime, shows a woman aged beyond her 67 years, her hair unstyled, bags under her eyes, a cigarette at her mouth. It is a provocatively honest photo of a woman worn down by love and life, but on the internet, where time is so easily erased, there is a photo of the young Elizabeth – and she is indeed the "good-looking blonde" that others in the book call her. I don't imagine George quite knew what he was getting, that here was a not only physical beauty but a verbal beauty. Their relationship was a difficult one, and it can't have been easy raising four illegitimate children. But still, that question that glows without fading: What do you live for then?

When I first read this book some years ago it left me dumbfounded. What powerful stuff, what a thing to experience, what a life to live. I felt unfeeling, unknowing, unlived by comparison. On what surface do I skate? Why can't I plunge to the depths? Then I looked around and I determined, by a simple act of emotional observation, that I too love my George Barker stand-in and that I too love my children, and this, with a love as dogged and deep, as visceral and guiding, as Elizabeth Smart's. Only mine is mostly unexpressed and undwelled upon, jostled aside by the intruding world and the endless errands of daily life – because I too have four children. A love that is lived has its prosaic aspects. Sure, there's love to be made, but there are also bills to be paid and groceries to be bought. And therein lies the greatness of Elizabeth Smart. She takes what is yours and mine, what is everyday and everywhere, what exists in every suburb and in every flat, and makes it mythical. You're not just Doris and Dave who live in Essex. You're also Tristan and Isolde, Romeo and Juliet, Dante and Beatrice, Elizabeth and George – only you don't know it, or you've forgotten it momentarily, or you just missed the boat (but perhaps it's not too late to catch the next one).

Read this book aloud, because while love is the theme, language is the plot, the character and the setting. It's a perfect book to be shared, to be read aloud to someone. And hopefully, as you are doing so, you will find yourself waking from a hundred-year slumber.

'By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept' is published by Fourth Estate

What makes the book a classic

By John Walsh

Elizabeth Smart is one of a small tribe of writers who have a cult following because of a single visionary work: others include Mikhail Bulgakov for The Master and Margarita, Djuna Barnes for Nightwood and James Hogg for Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Her achievement is slender but her reputation is secure, partly for the story of wayward passion that lies behind its creation.

She was born in 1913 in Canada, the daughter of a rich, distinguished and doting Ottawa lawyer – a girl who worshipped the idea of literature. As Yann Martel explains, she fell in love with the English poet George Barker's work in 1937 and, knowing nothing about him, instantly decided that she must have his children. They began to correspond. She brought him to California in 1940. Unfortunately for Elizabeth, George's wife Jessica came along too. Smart was pregnant when she sailed home to Canada in 1941. Two years later, as the war was raging, she came to England to re-join Barker. She gave birth to their second child, Christopher, and began working at the Ministry of Defence. It was then, in 1943, aged 30, that she wrote By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. The title borrows from Psalm 137: "By the waters of Babylon we lay down and wept."

Many readers have puzzled over what is going on in the book's early pages. It's a breathless record of summer 1940, when the Barkers lived with Smart in California, a record of her infatuation with Barker's physical presence ("he never passes anywhere near me without every drop of my blood springing to attention") and her frustration at the fondness George and Jessica show each other. Even Smart's annoyance that George lets his wife chop wood for the stove, while he lolls around the house being poetic, translates into erotic energy.

The book is a sustained hymn to love, its transcendent importance and everyday wonder. Only 2,000 copies were published in 1945, and it seems not to have had much impact at the end of the war. But its reputation spread by word of mouth and it was reprinted in 1966 to acclaim. In the preface, Brigid Brophy called it "one of the half-dozen masterpieces of poetic prose in the world".

Barker and Smart's dysfunctional folie à deux relationship sustained for 18 years. She had four children by him (he had 11 more by three other women). And he, by all accounts, was selfish and neglectful, constantly promising and failing to leave his wife. Elizabeth had to work in journalism and advertising to survive. She and her lover drank copious amounts, and hung out with the Bohemian artists and writers of the Sixties.

Smart became editor of Queen magazine and embraced bisexuality with enthusiasm. When Grand Central was reissued, she retired from London life, moved to a cottage in north Sussex, lived simply and alone, and wrote voluminously. In 1977, 32 years after Grand Central, she published a second prose work, The Assumption of The Rogues and Rascals and a collection of poetry, A Bonus. She moved back to her native Canada in 1982 as a writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta, but returned to England, where she died of a heart attack in 1986, aged 73.

Not everyone is a fan of the book or its author. The critic John Carey, reviewing her biography, identified "a broad streak of masochism in her make-up" and called her "one of literature's victims". Angela Carter regretted the way Smart let herself become a slave to George Barker's feckless mistreatment. Carter told a friend that one reason she helped found the feminist Virago Press was "the desire that no daughter of mine should ever be in a position to be able to write By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, exquisite prose though it might contain. (By Grand Central Station I Tore Off His Balls would be more like it, I should hope.)"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments