Writers' archives: A sad estate of affairs

Why do even left-wing writers like David Hare and Harold Pinter sell their papers to the highest bidder? Paul Taylor examines the vexed question of writers' archives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In his latest stage work, The Power of Yes, a verbatim piece about the credit crunch, David Hare makes one undeniable revelation. He keeps his money in the Post Office. It makes the scourge of political bad faith sound a strangely unworldly fellow. You'd never guess that he is married to Nicole Farhi, a fashion designer whose fame and fortune far exceed his. Are we to take it there was a prenuptial agreement whereby he undertook not to touch her wealth. If not, then you could argue that, in a play about finance, it is a mite disingenuous to pose as an innocent.

And you could equally make a case that it is inconsistent on the one hand to accept a knighthood from a grateful nation (on behalf of left-wing dramatists), while allowing your papers to drift in the direction of the money – in his case to the well-heeled Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. There is sometimes an interpretative link between how we regard a writer's work and how (a) he or she disposes of personal papers before death and (b) how his or her estate protects and pursues the posthumous interests of the said work.

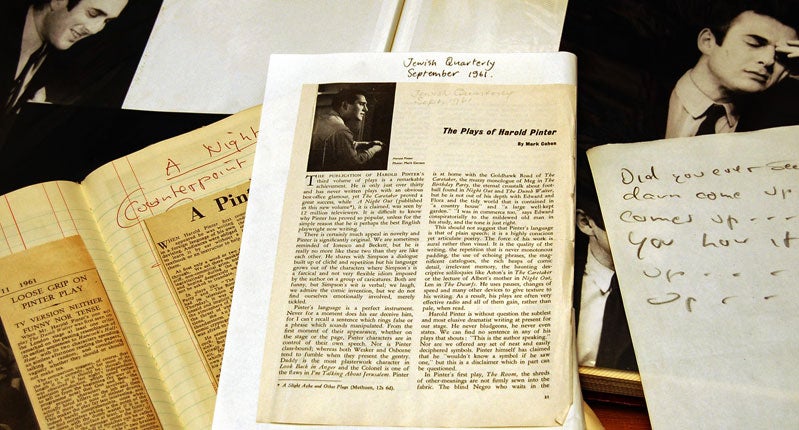

In the autumn edition of the excellent quarterly cultural magazine, Intelligent Life, Irving Wardle published a vivid and very funny account of his chequered friendship over several decades with the playwright Harold Pinter. Wardle was the chief theatre critic of The Times from 1963 to 1989 when he became the inaugural drama reviewer for the Independent on Sunday. But the friendship had begun when he was filling a fortnightly slot on the Bolton Evening News and Pinter wrote to thank him for the perceptiveness of his review of the critically mauled first production of The Birthday Party.

Wardle's essay brilliantly whips you into the intense physical presence of our premier dramatist of charged confrontation. It is an exemplary analysis of the difficulties inherent in any close relationship between a reviewer and the person reviewed; and it is an acute meditation on competing desires for control. Wardle ruefully acknowledges that when, as a critic, you adopt a new talent and pose as personal expositor, "you build him a prison from which he is bound to escape" and that Pinter had a particular need for control. His preferred mood was the unconditional. Downloaded like dreams, his plays are non-negotiable faits accomplis.

But in the composition of the Intelligent Life article, the drama of control was played out off the page as well as on. Literary estates have a duty to exercise control imaginatively in the interests of the creative afterlife of an artist's work and in the financial interests of the artist's beneficiaries. But they sometimes act with a counter-productive repressiveness. Wardle discovered this anew when he approached Pinter's widow, Lady Antonia Fraser, for permission to quote from letters in his possession that Pinter had written to him in the course of their relationship. Lady Antonia did not reply directly. Instead, a message refusing permission came through Pinter's agent Judy Daish. One of the grounds for their declining is that an edition of Pinter's letters is in preparation. You can question the ethics of attempting to prevent a private individual from quoting for fair comment from letters that belong to him.

And you can certainly puzzle hard over the fact that when Wardle's letters became known to the estate, no attempt was made to persuade the critic to lodge this material in the archive in the British Library. This is where Pinter's papers are housed, a privilege for which the dramatist, though a wealthy and classily connected man, charged the nation £1.1m.

The issue becomes faintly distasteful in light of the fact that Lady Antonia had no difficulty in allowing her own letters to Marigold Johnson (wife of Paul and a country neighbour) to be quoted in a sedulously approbatory piece by the latter. This appeared in the Evening Standard a matter of weeks after the ban on Wardle and celebrated "the love match of the decade" with its "insider's view of the relationship that scandalised London in the Seventies". I would hate to assume that Wardle is being permitted to fade from the collective memory bank on Planet Pinter because he fell out of love with the dramatist's later work.

There can sometimes be a discrepancy between the activities of an estate and the professed sentiments in the work. Brecht's play The Life of Galileo explores the dilemmas faced by a groundbreaking scientist who was barred from publishing his ideas by the Catholic Church. But with his National Theatre adaptation of the play in 2006, David Hare found himself in a strangely comparable position in relation to the Brecht estate. It refused to authorise a published text of his version, which had cut some of the Epic Theatre trappings.

With literary estates, difficult decisions have to be made over whether – and, if so, in what order and in what arrangements – to publish work that has not yet seen the light of day. Even when the highest principles and the keenest acumen are involved, mistakes can be made – as is true, I believe, in the instance of the Philip Larkin estate, which published a Collected Poems that gets rid of the volume divisions, in which the poet carefully ordered his poems, in favour of a promiscuous jumble of authorised and unauthorised works arranged in a chronological sequence. I would argue – against those women who, in an insult to the noble cause of feminism, mutilated Sylvia Plath's headstone in a desecrating attempt to remove his surname from it – that one of the heroes in the field of literary estates is the poet Ted Hughes.

He had the tremendously tricky job of guarding the interests (psychological and financial) of the children whom Plath's suicide had left bereft and of presenting and promoting work, left in a prejudicial plight interpretatively by her death, to its best advantage. He did not behave perfectly. He should not, for example, have destroyed her last journal, but remember that he is our sole courageous source for the fact that he did. In general, his labours on Plath's behalf do him credit.

With the performing arts, the crucial issue for estates is often the freedom (or otherwise) of interpretation. Samuel Beckett's heirs were notorious at one time for beadily monitoring new productions of his plays for the slightest deviation from the punctiliously precise stipulations he had made in the texts. The debate, though, is over whether – even in plays that attempt to dramatise the "eternal véritiés", as do those of Beckett – the same theatrical effect can be created by the same cause with the passage of time. Peter Brook has come up with the controversial but shrewd principle that, while the author's words should be sacrosanct in subsequent productions, stage directions are more period-specific and sometime actively need to be altered to remain true to the deep spirit of the piece in question. And it is good to report that the Beckett estate, which in 2006 lost a legal battle to prevent two identical female twins from playing Vladimir and Estragon in an Italian production of Waiting for Godot, has been vigilant in a less repressive way lately. They did not stop Peter Brook, in his brilliant reappraisal of the beautiful play Rockaby, from changing the mechanically rocked heroine who communicates in voiceover to a figure who speaks out directly and herself rocks an ordinary upright chair which she has at her side.

By this means, he and the sublime Kathryn Hunter were able to convey how this woman arrives at the wisdom whereby her suicide is a kind of tendering to herself the tenderness of auto-euthanasia.

The late-appearing hero of this article is Alan Bennett who refused a knighthood and gave his papers to the Bodleian gratis.

Nothing would please me more than to learn from the letters page of this paper that I have been cynical about Pinter and that the £1.1m of former public money has been invested for the furtherance of the causes that he espoused and championed more cryptically in the plays: civil liberties, the arts, and the after-care of torture victims.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments