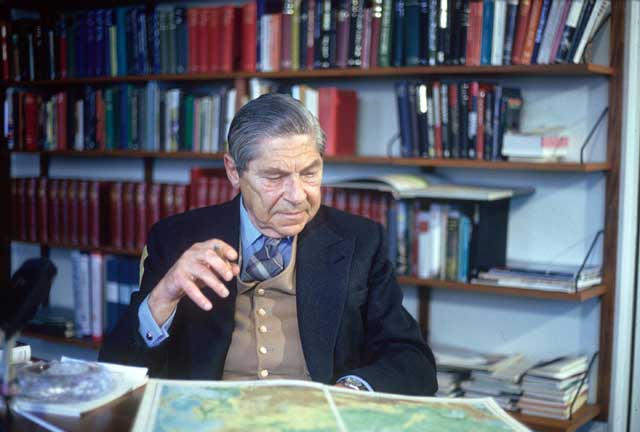

Utopia unlimited: Johann Hari assesses the legacy of Arthur Koestler

Rebel, partisan, campaigner: Arthur Koestler embodied the violent excesses of the 20th century, in both his intellectual and private life.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.History is a brutal sieve. Arthur Koestler is remembered now – if at all – for writing ‘Darkness at Noon’, a hand grenade of a novel tossed at Joseph Stalin’s Kremlin. Those two hundred pages are all we retain of an intellectual nomad who stormed across the twentieth century. He seems to have been everywhere, like an angry book-spewing Zelig. Even a thumbnail summary makes me feel exhausted (deep breath): He grew up in the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was one of the first Zionist settlers in Palestine. He became a star in the Berlin of Sally Bowles’ cabarets and a rising Adolf Hitler. He was jailed and nearly shot by General Franco. He fled the Nazis through Casablanca. He gave Albert Camus a black eye, George Orwell a holiday home, and Soviet Communism an enema. He had sex with supermodel twins, took magic mushrooms with Timothy O’Leary, and helped create Intelligent Design. Oh – and he was a rapist.

Michael Scammell’s terrific new biography – ‘Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth Century Sceptic’ – scrapes together a contradictory life that amounts to far more than the single novel that keeps him on our book-shelves. George Steiner said of him: “There are men and women who seem to embody the times in which they live. Somehow their biographies take on and make more visible to the rest of us the shape and meaning of the age.”

Koestler was a 5’6 cocktail of raw nerve endings and hard booze. All his life he kept snarling barely-tamed dogs, and his manner matched theirs. If you clashed with his ideas over dinner, he could pick up the restaurant table and hurl it into the middle of the room. His sometime-lover Elizabeth Jane Howard said you felt that if you touched him “you would get an electric shock.” To him, ideas were more real than people. As Scammell puts it: “He experienced the onset of fresh ideas like orgasms, and mourned their passing as the end of treasured love affairs.” He is a character from Dostoyevsky, flinging himself off the page and into the twentieth century.

He was born in 1905, and he nearly killed his mother there and then. She was 34 – a seriously old age at that time to have your first child. The labour took two agonising days. Koestler later wrote: “The whole unsavoury Freudian Olympus, from Oedipus Rex to Orestes, stood watch at my cradle.” He liked later to claim his family had flared up from nothing into sudden wealth and then vanished just as fast into exile or the gas chambers. It wasn’t true: his mother was from one of the richest Jewish families in Austro-Hungary. But Koestler wanted to deny everything about her, always. She was ill and depressive, and even trips to Sigmund Freud couldn’t iron her out: she said he was “a pervert.” Her sniping rejections of her son – and her abandonment of him for years as she went off on “rest cures” – created in him a sense of guilt and inferiority that became his conjoined twin. Even when she died at the age of 99, he raged that it was her “final act of selfishness” to “keep me there holding her hand until she died.”

He became a sullen, friendless boy, passively absorbing all the anti-Semitic hatreds of the time and turning them in on himself. It was only in his late teens that he found his first true family: he joined the Jewish frat-houses of Vienna. He compared their bouts of drinking and duelling to group therapy, stripping away his shyness. But there was an air of rising hate: in his university, Jews were being beaten with sticks by angry mobs howling “Jews out!” Then one day a visiting doctor delivered a lecture saying there was a new world waiting for the Jews, to be built in Palestine. It was to be Koestler’s first intellectual intoxication.

He saw the creation of Israel as a cure to his Jewishness, which he regarded as a curse. He raged against the “intelligent monkey face” of Jews with “thick, curved noses, fleshy lips and liquid eyes”, saying they resembled the “masks of archaic reptiles.” He immediately converted to the most hardcore strain of Zionism available – that preached by Vladimir Jabotinsky. He demanded the immediate bombing of British imperial forces in Palestine, and the total ethnic cleansing of Arabs from the river to the sea. Koestler turned him into the father he had been waiting for – tough, stern, and offering total certainty.

He charged off to his first Promised Land, joining a settlement in Palestine. But the hangover was immediate. He wrote: “I found myself in a rather dismal and slumlike oasis in the wilderness consisting of wooden huts surrounded by dreary vegetable plots.” He was a fratboy sent to dig cabbage patches. The settlement rejected him and, stranded, he found himself sleeping on beaches and going hungry for days on end. He managed to finagle his way into journalism. He began to feel some cognitive dissonance. He could see that innocent Palestinians lived there and didn’t deserve to be driven out – but he shunted it aside, saying he would develop “schizophrenia” if he thought about it too much.

He later used this time as material for his novel ‘Thieves in the Night’, which sympathetically depicts a Jewish terrorist planting bombs because he has been denied a state of his own. It reads with an ironic after-taste today, now that Palestinians are planting bombs in the same place for the same reason. But at the time, he soon grew bored. “I had gone to Palestine as a young enthusiast,” he said, but instead of the Promised Land “I had found reality, and extremely complex reality which attracted and repelled me.” On a steamship, he met a girl who told him there was another Promised Land waiting – and its Messiah was named Lenin.

Koestler arrived in Berlin in 1930, just as the Nazis were beginning to rise in the Reichstag. Still in his twenties, he became a superstar journalist, interviewing Einstein and being flown to the North Pole – but he went looking for the Communists. As befitted his black-and-white world view, he became convinced they were the only real opposition to the Nazis. He wrote: “To say that one had ‘seen the light’ is a poor description of the mental rapture which only the convert knows. The new light seems to pour across the skull; the whole universe falls into pattern like the stray pieces of a jigsaw puzzle assembled by magic at one stroke. There is now an answer to every question. Doubts and conflicts are a matter of the tortured past – a past already remote, when one had lived in dismal ignorance in the tasteless, colourless world of those who don’t know.”

He went to the Soviet Union, and trained himself not to see. Yes, the starved famine-victims lay slumped all around, dying in their millions. Yes, the prisons he glanced at were full of political prisoners. But he went home and wrote passionately pro-Soviet books that didn’t mention them once.

Like so many intellectuals of his generation, he joined those who flocked to the Spanish Civil War, believing it held the key to Europe’s future. When the Republican troops fled from Malaga, he stayed to witness their arrival – a moment of real courage. He was slammed into Franco’s jails, and saw other prisoners being executed. He began to realise how wrong he had been to dismiss the freedom of the individual – and to glimpse how Bolshevism terrorized people into obedience. The people he had seen in the Soviet Union weren’t acquiescing; they were broken. When he was freed, he met with a friend in France who had been held in a Soviet jail – and found her experience was exactly the same.

He became one of the great left-wing opponents of Communism. In a fever, he wrote ‘Darkness at Noon’, the story of a senior revolutionary who is jailed, and is so convinced by the rightness of The Cause that he accepts his own execution – even though he had done nothing. It was the story of the show-trials, as told from within. As France fell to the Nazis, he was detained again, and escaped again.

After the war, he played a crucial role in exposing the despicable apologism for Soviet tyranny on much of the European left. He fell out with Jean-Paul Sartre (and slept with his wife for good measure), and damned Bertolt Brecht, who remained silent even after his first wife “disappeared.” But he started to preach an uncritical support for US foreign policy that was almost as simplistic. He scorned those who said Western Europe should be an independent democratic third-force, declaring: “There will either be a Pax Americana or there will be no Pax.” To those who pointed out this “Pax” didn’t look so peaceful when it was toppling democracies in Iran, Guatemala, and Chile, he had no answer but rage. He could never acknowledge political greys.

This may have been due to his brain chemistry. Koestler seems to have been a manic depressive, medicating himself with enough alcohol to stun a mule. It meant he couldn’t stay with a cause for long. Indeed, he referred to himself as the “Casanova of causes,” wooing them tenderly, bedding them, and then storming out in the morning without leaving his phone number. He ditched Messiahs in his life, but he never ditched Messianism. He said he was cursed with “absolutitis”: when a cause didn’t offer him absolute salvation, he would discard it in despair, and try to find another with the same promise. Koestler’s life can be read as a parable about the folly of utopianism in politics. There will never be a frictionless world in which political disagreement evaporates and everyone accepts Perfection. If this is your life’s cause, you can only end up denying reality, or broken.

In his last few decades, this impulse led him to charge off in a bizarre direction. He became convinced there was a “controlling intelligence” in the universe – and it could be accessed via ESP, levitation, or magic mushrooms. He began to claim Galileo was a charlatan who cruelly attacked religion and Darwinism was wrong, and tried to outline a “science” that would prove the universe was planned – anticipating the gibberish of the Christian fundamentalist right. Then he got stranger still. He began to claim human beings had irredeemable defects in the brain that could be resolved by putting us all on tablets that would serve as “mental stabilizers.” All hope for a political revolution burned out, he began to pine for a pharmacological revolution. His last Promised Land lay in a bottle of pills.

Scammell tells all this is plain and cool writing that makes Koestler seem all the more feverish. The excellent biography only falters when it comes to dissecting Koestler’s greatest flaw: his abuse of women. Here, Scammell becomes defensive and, in one passage, unforgivably apologetic. Koestler’s first wife got him rescued from Franco’s prisons – but when the Nazis invaded France, he abandoned her, and took another woman to safety. Koestler’s second wife was seriously ill – but he still punched her in the head. Koestler’s third wife was only 55 and entirely healthy when he committed suicide after contracting Parkinson’s – but he still let her kill herself with him.

Scammell describes Koestler’s frenetic sex-life as a “merry-go-round”, but it was more a misery-go-round. Koestler wrote: “Without an element of initial rape, there is no delight.” But when it comes to describing his only documented rape, Sammler starts to make extraordinary excuses. Jill Craigie – one of Britain’s best feminist writers, who I knew a little – revealed after his death that one morning Koestler had pulled her hair, throttled her, and raped her. But Sammler complains this news has “provoked a stream of righteous abuse of Koestler that continues to this day.” Righteous abuse? No: it is measured criticism of a disgusting crime. He says we need to keep it “in proportion”, and claims “the exercise of male strength to gain sexual satisfaction wasn’t exactly uncommon at that time… He almost certainly behaved like thousands of other men of his generation.” But throttling a woman and forcing her into sex was regarded as a serious crime then too. To excuse it is beneath a writer of Scammell’s calibre.

In a century of serial fanaticisms, Arthur Koestler embodied both the disease and the cure. He was a fanatic capable of sobering up, an ideologue who occasionally let reality in through the cracks. He never led us to the promised land—but he did show us why it is a mirage, dragging us away from the real and relentless work of reform.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments