The unbearable betrayal of Milan Kundera?

The dissident Czech author whose books famously satirise the Communist system was accused yesterday of denouncing a young Western spy in the 1950s. As Anne Penketh reports, it is a claim he vehemently denies

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

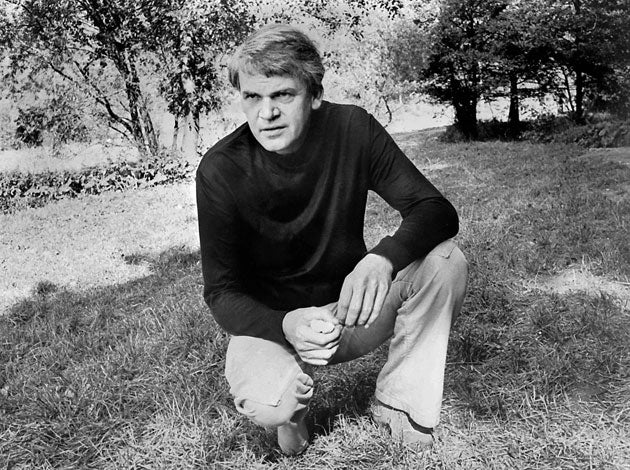

Your support makes all the difference.In a sensational plot line that could have come straight from the pages of one of his own novels, the acclaimed Czech-born writer Milan Kundera has been accused of denouncing a Western spy to the Communist secret police when he was a student.

The author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being was identified by a Czech state institute yesterday as having betrayed the young man in 1950 at the height of the Communist show trials.

Kundera, one of Czechoslovakia's best-known writers, who moved to France in 1975 as a dissident, bitterly satirised the Communist system in novels such as The Joke and Life is Elsewhere.

The reclusive Kundera, now 79, categorically denied the accusation yesterday, accusing the institute and media of "the assassination of an author". He said: "I am totally astonished by something that I did not expect, about which I knew nothing only yesterday, and that did not happen. I did not know the man at all."

The spy at the centre of the allegation was Miroslav Dvoracek, a young pilot who fled Czechoslovakia after the 1948 Communist takeover, was recruited in Germany by US counter-espionage agents and sent back to his homeland. According to the government-sponsored Czech institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, Mr Dvoracek visited a woman in Prague and left a suitcase in her student dormitory. She told her boyfriend, who later told Kundera, and Kundera, it is claimed, went to the police.

Mr Dvoracek was arrested when he came to collect the suitcase, and it was initially believed that he had been betrayed by his girlfriend. He was later sentenced to 22 years in prison for desertion, espionage and treason, although he served a total 14 years, mainly spent working in uranium mines as a political prisoner. The institute said that a document written by the Czech secret police, and unearthed by a team of historians, identified Kundera as the person who informed on Mr Dvoracek.

Although informers were a tool of the totalitarian system which blackmailed its citizens to ensure loyalty, the charges against Kundera could seriously undermine his reputation in his native country as the scourge of Communism. The former Soviet bloc has been torn apart by the revelations of its Communist-era secret files, and Czechoslovakia was one of the first to publish the identities of informers, in 1991. Germany followed suit by releasing its East German Stasi documents in 1992.

In Poland, authorities have been accused of using the files in order to settle political scores, with the former president Lech Walesa accused of being an informer by the current President, Lech Kaczynski, and his twin brother, and former prime minister, Jaroslaw.

In the Czech Republic, the institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes – which is widely viewed as credible – has been tasked with collecting and publishing the Communist-era files. Among its goals it mentions the "research and nonpartisan evaluation of the time of oppression and the period of Communist totalitarian power, research of antidemocratic and criminal activities of state structure, namely its security forces, and the criminal activities of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and other organisations based on its ideology."

Like most Czechs of his age, Kundera joined the Communist Party as a student, but was expelled after criticising its totalitarian nature. He wrote about his experience in his first novel The Joke, in which a playful anti-Communist message on a postcard leads to tragedy.

He went on to examine the difficulties of personal relationships, often set against a political background, in subsequent works which included The Unbearable Lightness of Being. That novel was written in Paris but set against the background of the Prague Spring of 1968 and the liberal reforms of Alexander Dubcek, crushed by Soviet tanks. The book contributed to the writer's international reputation after it was turned into a film, although Kundera repudiated the filmed version.

Kundera's works were banned in Czechoslovakia until the Communist collapse, and he was granted French citizenship in 1981. But some say that his best works are behind him now that his Communist muse is gone. in later works, such as immortality and ignorance, he concentrates on the personal and the art of writing, rather than the political.

As for his alleged victim, Mr Dvoracek is now aged 80 and living in Sweden in poor health after suffering a stroke. His wife, Marketa, told the AFP news agency yesterday that the couple was "not surprised" that Kundera's name had surfaced in the Czech media reports. He is "a good writer but I am under no illusions about him as a human being," said Marketa. As for her husband, he "knew he was informed on, so who did it makes no difference to him now".

From Prague to Paris A literary journey into exile

*During the 1980s, Milan Kundera became, without much doubt, the most fashionable and widely praised writer on the planet. He wrote rueful, sensual, ironic novels of Czech life in the dog days of a bankrupt communism. They established a benchmark for the sophisticated fusion of private and public life in fiction, with a blend of essayistic wit, "postmodern" ingenuity and erotic edginess that spawned a host of imitations.

Born in Brno in 1929, he studied literature and film, and taught at the Prague film academy as a reform-minded but still outwardly loyal member of the Communist Party. His first novel, The Joke (1967), satirised the Czech Stalinism of the 1950s, and heralded a final expulsion from the Party, which came in 1970. Kundera left for Paris in 1975. But the novels that established his reputation – The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1978) and The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) – remained rooted in the emotional, sexual and intellectual life of Prague. After Immortality (1990), he began to write in French, and many fans drifted away from the thinner and more abstract style in books such as Ignorance (2000). Yet his renown as a thinker and critic grew rapidly, with the essays of Testaments Betrayed (1992) and an elegant study of the meaning of the novel, The Curtain (2005).

Boyd Tonkin

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments