The role of modern media in the liberation of Paris 1944

The author of Eleven Days in August remarks on the contrast between revolutions in the digital age and those decades ago. But some things haven't changed, says Matthew Cobb

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s hard to countenance in an era when political uprisings – such as those in Syria and Libya - are immediately documented by tweets, blog posts and the uploading of videos but the first multimedia insurrection took place nearly 70 years ago, in Paris.

The internet has transformed the way that information is shared when countries are undergoing revolution – but many of the tactics involved in winning such critical communications battles were pioneered by the media workers of the French Resistance, including famous names such as Robert Doisneau and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

As the Allied armies finally broke through the German lines in Normandy in August 1944, the collaborationists fled the city and the newspaper reporters, photographers, cinematographers and radio broadcasters of the Free French promptly moved in to fill the media vacuum.

In the Paris equivalent of Fleet Street, around the Rue de Réaumur, presses that for four years had spewed Vichy propaganda became still. Journalists from the Resistance took over the newsrooms, having previously run incredible risks producing a huge range of underground papers.

But with the threat of a tank attack against their offices, the impatient journalists had to wait four days before the first newspapers appeared. Paper rationing meant that they all had the same format – one-page broadsheets – and the same price. Sold on the street, often in front of increasingly powerless German patrols, they were snapped up by the Parisians, hungry for news – even if much of it was incorrect.

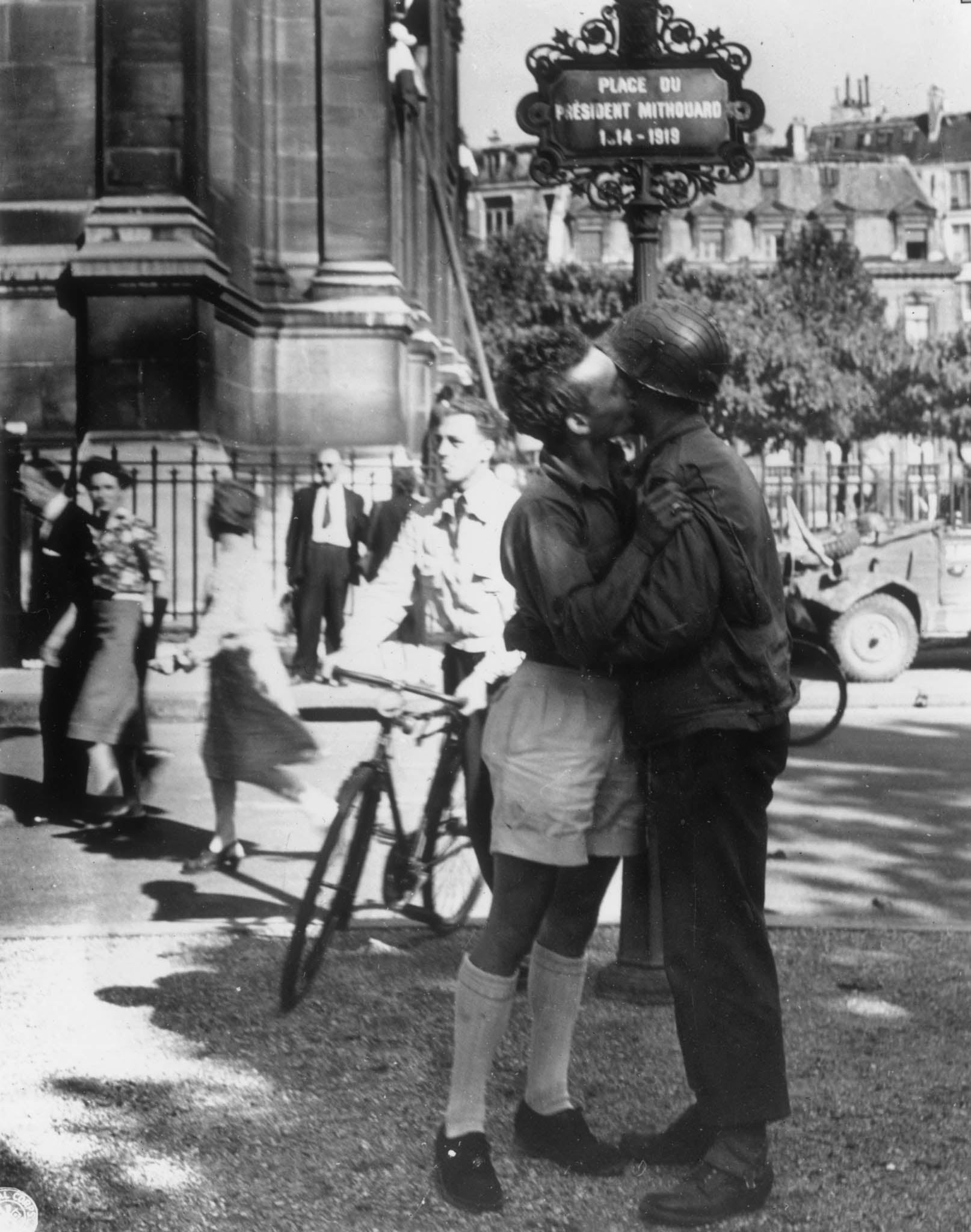

The newspapers contained poorly-printed photos. From the moment the insurrection began, scores of photographers – including Doisneau and Cartier-Bresson – pooled their resources and divided up the city. The Resistance told them where there would be operations and they turned up to capture the moment. Thousands of pictures were taken of the events by the photographers, and by ordinary Parisians, who took their cameras and their precious film and went down into the midst of the fighting to record those historic events. These photos – some of them works of art, some of them mere snaps – helped create the popular image of the insurrection.

Cinematographers joined in. Thousands of feet of film were assembled by another cooperative – the Parisian film-makers. They covered every part of the events, and the film was rapidly assembled into a 30-minute newsreel account which was seen around the world. Like today’s YouTube videos, this film framed memory, shaping the way the event was perceived, including by the Parisians themselves.

The final element of the multimedia insurrection was the radio. Radio-Paris, the voice of Vichy France, had fallen silent when the collaborationists fled. In the evening of 21 August, the Resistance radio station in Paris was finally allowed on air, and over the next three days it broadcast news of the fighting and interviews with key Resistance leaders, often with the sound of gunfire in the background.

The most important function of the media was its ability to organise and mobilise the population. The radio relayed calls for help from barricades, telling Parisians where they could go to help in the fighting. It relayed information from one neighbourhood to another, warning of German troop movements. The newspapers carried instructions for how to prepare makeshift weapons like Molotov cocktails, and told people where they could take the wounded. Just as with today's social networks, the media in the Parisian insurrection organised people in a common cause.

The Free French service on the BBC, which began in the summer of 1940, were used to manipulate events. At lunchtime on 23 August it broadcast the completely false announcement that Paris was liberated. Parisians were stunned and furious – German tanks were still prowling the streets and hundreds of people were being killed or injured each day. Allied Headquarters was equally angry.

The fake message went all round the world – bells were rung from New York to Manchester, while the War Cabinet in London ordered a celebration mass in St Paul’s. The next day the whole thing was explained away as a mistake in translation. But there was no mistake – the whole scheme had been cooked up by Georges Boris, the head of Free French propaganda, in order to speed the Allies in their advance on the capital.

Radio redeemed itself the next day, when liberation really did begin. On the evening of 24 August, the Resistance broadcast continuous updates as a Free French armoured column came into the heart of the city, and then called on all the churches in the city to ring their bells in celebration.

The final event in the insurrection was also the high point of media coverage. On 26 August, General de Gaulle, and the Free French and Resistance leaders marched down the Champs Elysées on a boiling hot afternoon. Accompanied by tanks, and surrounded by the largest crowd Paris has ever seen, de Gaulle’s slow progress was captured by dozens of film crews, radio commentators perched on top of cars, and by scores of press photographers. These joyous images, which were sent round the world, came to represent the Liberation of the whole of France. Then, as now in the digital era, the media not only recorded history, they helped shape it.

‘Eleven Days In August’ By Matthew Cobb, the story of the liberation of Paris, is published on 25 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments