The prime of Miss Muriel Spark

Fifty years old but as sharp as ever, 'The Girls of Slender Means' saw the author at her very best, says AL Kennedy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Published in 1963, The Girls of Slender Means shows us Muriel Spark at her very best, in her forties and a fully mature novelist of insight and ambition. This is an uncompromisingly well-crafted book: lean, ironic, funny, penetrating, unsettling and very, very beautiful. Welcome to the English language as operated by an expert.

When Spark wrote The Girls of Slender Means, she had already experienced the disciplines of a wartime propaganda office, witnessing the dark subtleties and power of language in action. This may be, in part, why her writing is more than averagely aware of the human ability to change reality with fictions, to kill, or to save, with a properly placed word.

Spark was accepted into the Catholic Church in 1954, her conversion in part effected by a close reading of religious texts and letters – words to define and change the soul and the meaning of the world, to say nothing of challenging Spark's not inconsiderable will. She remained devout, determined and yet imaginatively undogmatic within her belief. When confronted by Spark's uncanny ability to penetrate her characters' interior workings it is hard not to see her sometimes as their unreliable confessor – the one who receives their secrets in the dark and then makes them plain to us as entertainment, warning and consolation.

There is a type of scientific disinterest in her ways of showing how easily humans can lose their humanity, not because of evil, not because of something as clear-cut and condemnatory as Original Sin, but certainly because of their nature – fascinating, wonderful, but also individually and epidemically flawed.

After leaving school, this most economical of writers decided to take a course in précis writing. With hindsight, this seems a little like a hawk taking flying lessons, but it also speaks of an early dedication to her craft. Already a schoolgirl poet, undoubtedly an author by vocation and unsparing of herself, Spark, it seems, was being shaped from an early age by her need to become the writer she must.

Both personally and professionally she often seemed to set herself tasks and limits in order to overcome them. She balanced the disciplines of language, spiritual reflection and the dedication of long hours at her solitary work with marvellously transgressive thought, a kind of intellectual riot, and fictions that reach out to the reader and share quietly devastating observations. The experience of a harmless curate, soon swept up into war, is summarised with: "he later learned some reality". Descriptions are balanced just on the right side of nonsense, as with Anne Baberton's "casual hips" – the phrase is at once funny, charged and densely communicative. And that darting, intelligent humour is often flickering beneath apparently innocent phrases. Spark tells us of "young female poets … or at least females who typed the poetry and slept with the poets, it was nearly the same thing". Jane Wright, the punning writer of fake begging letters and then journalistic gossip, is at one point described as "incorrectly subscribing to a belief that she was capable of thought".

Discontented Jane is "a fat girl who worked for a publisher and who was considered to be brainy but somewhat below standard, socially". She is also an immature author who writes poor poetry and will become a journalist of the more degraded type. With poetry and publishing Spark is very much on home ground: she had been a controversial General Secretary of the Poetry Society and was variously hated and adored by the poets of London. She had also worked in "the world of books" and had a consistently prickly relationship with her own publishers. Both these elements perhaps lead to the gleeful depiction of the small publishing house which employs Jane as its only assistant. Huy Throvis-Mew Ltd seems an endless source of hapless skulduggery, mainly due to its owner, who manifests as a kind of moral and intellectual absence and burns with a mission to demoralise and oppress those he publishes. Jane can be read as a reflection of Spark, but she is also plainly the opposite of Spark's kind of writer – Jane is morally compromised, unexacting and parasitic.

The Girls of Slender Means depicts a post-war Britain where propaganda has never convinced and victory has not produced a nation of noble heroes and chaste heroines, builders of a better world. Symbols of power and order – Churchill's radio broadcasts, the wonderfully hideous Albert Memorial and the distant, puppetlike royal family – are destroyed by the force of ridicule. This background is unnerving, or perhaps exhilarating, but never bluntly cruel. Spark is not misanthropic; she punishes hubris, not humanity. Pretence, unkindness, self-deception and our inability to understand our own unimportance are her targets, and under them runs a sense that there are better ways: gentleness, relationships based on mutual regard, perspectives that approach eternity.

Spark loved to set her characters inside the pressures of microcosmic worlds: a desert island, a girls' school, a nunnery, a small community, the shrinking horizons of senility. During the war she had been an observant and slightly aloof resident of the Helena Club in London – a hostel for women largely younger than herself and all of them most certainly of slender means. This wouldn't be the last time she'd experience the charms and irritations of communal life. (Her early and disastrous marriage aside, Spark's life avoided conventional domesticity and conventional relationships, but she lived alone relatively rarely.)

Alongside the glitter and humour and the unbridled insight of the novel is its ultimate destination: a frenzy of panic, of undeserved death, fear and indignity. And in the chaos bloom degradation, transfiguration and one act of iconic and life-changing selfishness. It is a testament to Spark's abilities that in her hands a short tale about apparently trivial subjects inhabiting a bygone age can leap at the reader to shake their soul. The Girls of Slender Means is delightful, ingenious, movingly lovely and savage. It is also a deeply spiritual book.

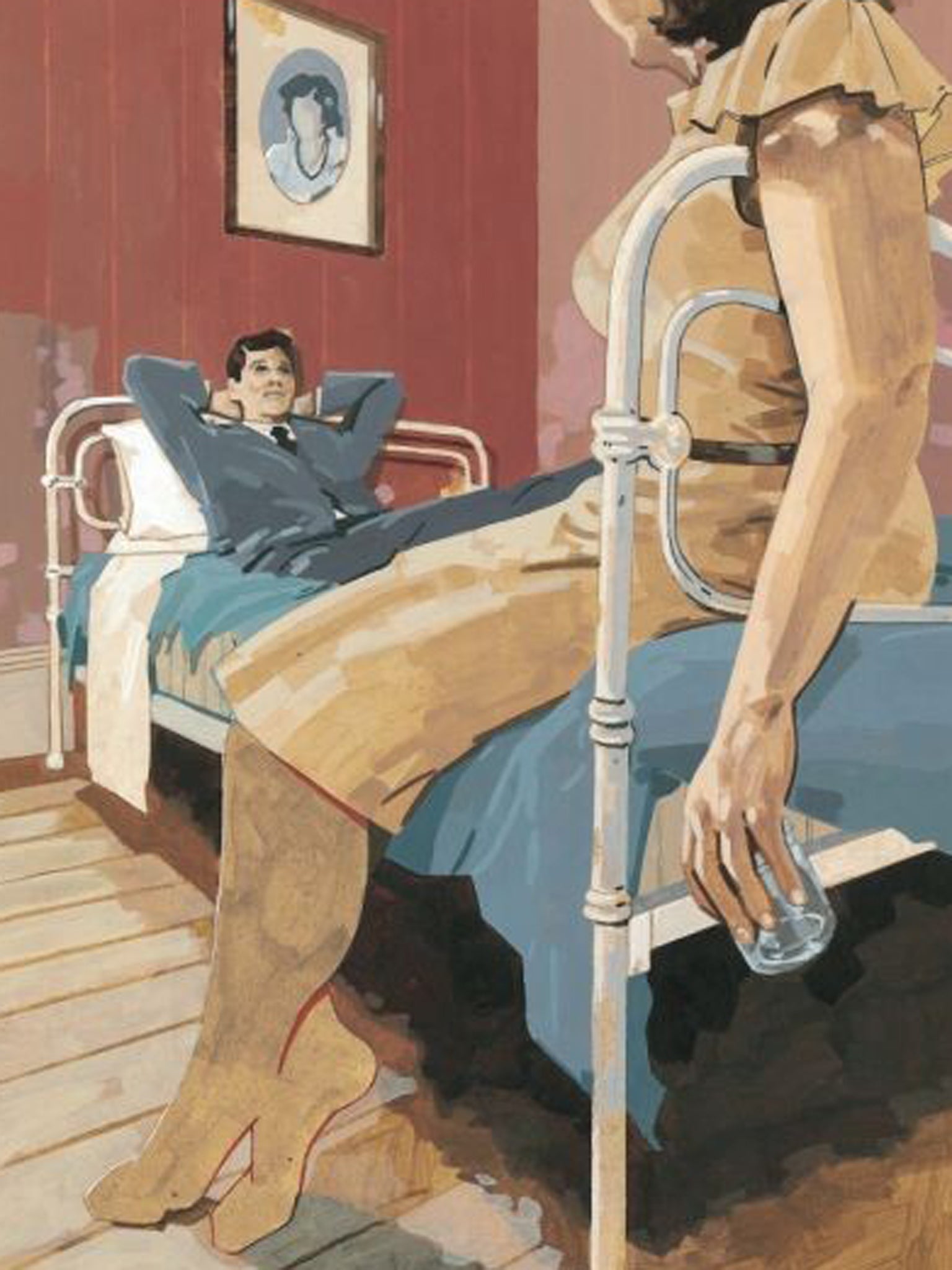

This is an edited extract from A L Kennedy's introduction to a new edition of 'The Girls of Slender Means' by Muriel Spark, with illustrations by Lyndon Hayes (The Folio Society, £24.95, foliosociety.com)

The Girls of Slender Means by Muriel Spark

The Folio Society £24.95

"All the nice people were poor, and few were nicer ... than these girls at Kensington who glanced out of the windows in the early mornings to see what the day looked like, or gazed out on the green summer evenings, as if reflecting on the months ahead ... Their eyes gave out an eager-spirited light that resembled near-genius, but was youth merely ..."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments