The Bunker Diary: Should books have happy endings?

Doom-laden tales such as 'The Bunker Diary' may impress prize juries, but, argues Amanda Craig, books that offer hope are the ones that children remember with love [spoiler alert]

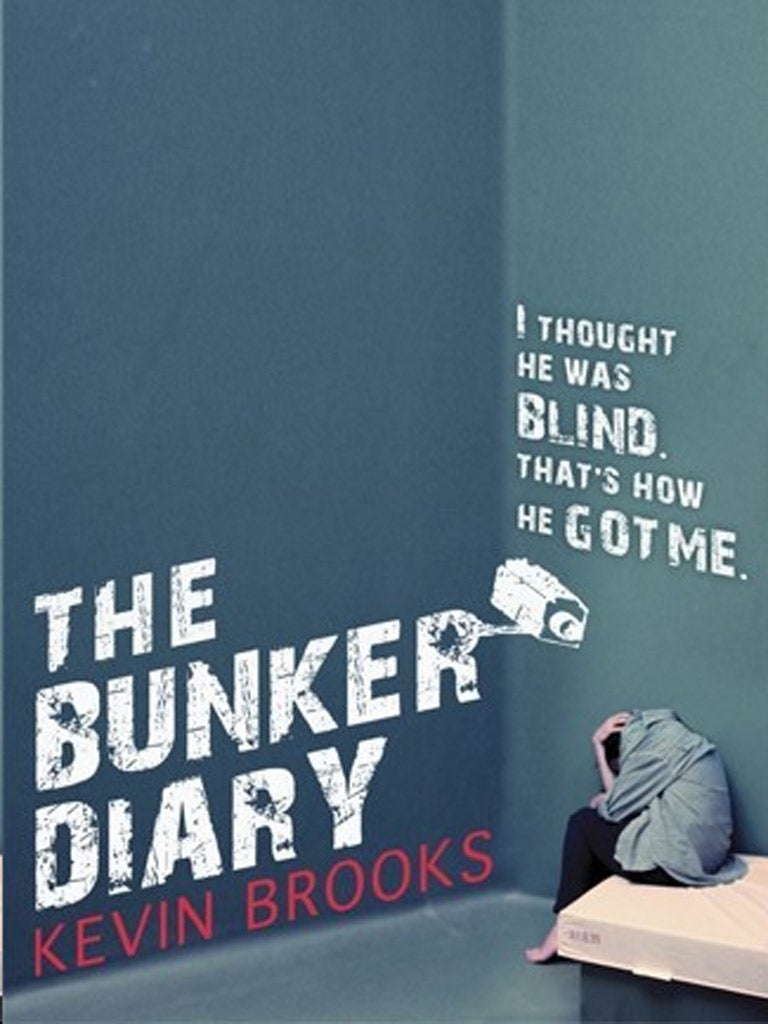

One of the questions I most often get asked when giving talks or lectures about children's literature is, "Why are Carnegie Prize-winning books always so gloomy?" To this, I can give no answer, but in giving this year's prize to Kevin Brooks's The Bunker Diary, it has form.

There is Sally Gardner's Maggot Moon, set in an alternative 1950s fascist Britain in which the dyslexic hero is killed. There is Patrick Ness's A Monster Calls, about a boy whose mother is dying of cancer, from an idea of the late Siobhan Dowd's. There is Melvin Burgess's Junk, about heroin addicts. And so on and on – right back to C S Lewis's The Last Battle, in which the human children we have loved die in a train crash and Narnia itself is extinguished. The occasional book with a happy ending such as David Almond's Skellig and Frank Cottrell Boyce's Millions seem almost accidental choices in the roll call of doom.

It goes without saying that all of the above are brilliant writers who should be in every library. But whether these particular books are the ones that make children love reading, and which we remember with love, is another matter. Children's literature is a vast field, ranging as it does from astoundingly sophisticated picture books to Young Adult fiction such as Meg Rosoff's How I Live Now. However, until very recently it was a genre that conformed to one rule: no matter what the protagonists went through, it must end happily.

Childhood is always thought of as a golden age, but children all over the world can and do suffer from bullying, loneliness, hunger, bereavement, betrayal, violence and terror. The reason why this literature is particularly important has little to do with literacy, and everything to do with the way that it mirrors what children themselves all too often endure. Stories give suffering a voice, but where children are concerned, they also give hope. Salvation will come about, through magic or luck or your own efforts as a moral person who does not give up.

We love heroes and heroines from Peter Rabbit to Harry Potter because we know that no matter how bad things get, they will return stronger and happier through what they've learnt, and that their experiences will enable them to restore justice. Every work of fiction that we take to our hearts, up to and including Jane Eyre, The Odyssey or Pride and Prejudice, follows this template. A great work of tragic fiction brings about catharsis, but on the whole, we need the consolations of children's fiction far more.

Not every classic has what you might call a conventional happy ending: the boy in Roald Dahl's The Witches gets turned into a mouse, and never returns; at the finale of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, Will and Lyra must be parted for ever; the hero of John Boyne's The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas chooses to die in the gas chambers with his imprisoned friend. Though all have been made into successful films, my guess is that none of these novels will continue to be read with enthusiasm by future generations because of the way they end.

Kevin Brooks's novel isn't intended for children but for teenagers, an audience that claims to despise the happy endings of childhood literature (though a good many secretly continue to read it precisely because it offers comfort). They embrace weepie love stories such as John Green's The Fault in Our Stars, in which both boy and girl are dying of cancer, and gorge on dystopias that amplify their feeling that capitalism and corrupt politicians have destroyed their future chances of employment.

Yet even here, optimism keeps bubbling through. The "snuff" stories about dying kids who have sex before dying make one suspect that this sub-genre is really harking back to the old Romantic idea about how it's fine to cease upon the midnight with no pain if you're beautiful and adored. The dystopias described by Suzanne Collins's The Hunger Games trilogy and its many rip-offs spice up their heroine's troubles by having her needing to choose between two hot boys. No matter how high the body count, the hard-edged horrors of Orwell's 1984 and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World never penetrate. They are still comfort reads.

Brooks's story of kidnapped kids who never escape from their prison offers no more hope than John Fowles's The Collector – which it echoes without ever achieving Fowles's humanism, poignancy and gorgeously literate style. It is depressing both in its nature and its lack of redemption; as a children's critic, I refused to review it on publication. Brooks has written so many better books than The Bunker Diary that it is deeply ironic the Carnegie should have chosen this one, out of an otherwise engaging oeuvre, to celebrate and promote. It is the latest in a trajectory for the Carnegie prize which nobody who loves children's books can possibly applaud.

Amanda Craig is a critic, columnist and novelist. Her books include 'A Vicious Circle', 'In a Dark Wood' and 'Hearts and Minds' (Abacus, £8.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments