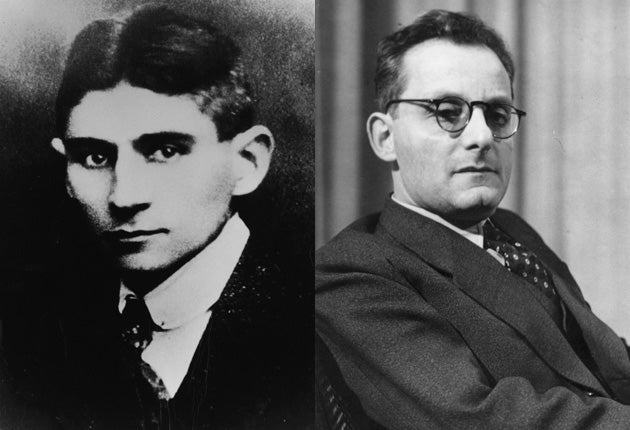

The bitter legacy of Franz Kafka

A milestone has been reached in the battle over the ownership of the author's unpublished papers. Tony Paterson reports

The treasure trove of unpublished Kafka works is said to contain thousands of decaying manuscripts, postcards, drawings and letters composed by the Czech-born, Jewish writer who is considered one of the most brilliant and revolutionary German language authors of the 20th century.

Yet for more than 40 years, the huge cache of unseen yet potentially vital Kafka literature lay stacked in piles in a humid, cat-infested first-floor flat in a suburb of Tel Aviv. Watching over them was the former secretary of Max Brod, the author's friend who claimed to be protecting his legacy.

Yesterday, after a legal battle lasting more than two years, papers from the hidden Kafka collection began to emerge from the vaults of a bank in the Swiss city of Zürich. A group of German literary and manuscript experts are now assessing their importance – possibly the first readers of the documents since they were written more than 80 years ago.

The sheer volume of the cache may lead to a radical re-assessment of the reclusive and psychologically tormented author, who died from tuberculosis, aged just 40, in 1924.

The pile of hidden documents has caused feverish excitement in the literary world for decades. There has been speculation that Kafka's lost papers could contain unpublished works by the author of masterpieces such as The Trial and The Metamorphosis, or at least the manuscript of his unfinished novel: Wedding Preparations in the Country. "Whatever they contain, they are bound to be of huge value to Kafka research and could shed new light on the author's complex personality," said Wilko Steffens of Germany's Kafka Society.

Just why it has taken so long for the hidden manuscripts to see the light of day is a story of Kafkaesque proportions in itself. Born in Prague in 1883, Franz Kafka – whose surname means "magpie" in Czech – was a little-known Jewish writer with a handful of published German stories to his name when he died.

However, just before his death in a Vienna sanatorium, the ailing writer entrusted his friend, Max Brod, with his collection of unpublished handwritten documents, famously insisting that all the papers "should be burned unread and without remnant" after his death.

Yet Brod, who like Kafka was a member of Prague's German-speaking Jewish community, blatantly ignored his friend's last wishes and chose to publish several key works including The Trial, The Metamorphosis and The Castle, quickly securing Kafka a posthumous place among Europe's literary giants.

With the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, Brod, who was an ardent Zionist, stuffed Kafka's collection of manuscripts into a suitcase and fled to Israel. He quickly settled, setting up home in Tel Aviv and employed Esther Hoffe, a fellow German-speaking Jewish refugee from Prague. Hoffe became Brod's housekeeper and secretary (and – it is rumoured – his lover). Brod died in 1968, having passed some of the Kafka documents on to Israeli public archives. However he left the rest of the manuscripts with Esther. For the next four decades, the papers remained stacked in unseemly heaps in her dingy ground-floor Tel Aviv flat, which was inhabited by dozens of free-roaming cats.

Nurit Pegi, an Israeli academic who is writing a dissertation on Brod, explained that, ever since, academics have been forced to guess what the documents contain. "It is an outrage that no one was allowed to see them," he said.

Hoffe claimed it was her right to do what she wanted with the documents and indeed sold several items from the archive at auction. At Sotheby's in 1988, she sold an original manuscript of The Trial to a book dealer acting on behalf of the German literary archive in the city of Marbach. The manuscript fetched £1.1m. On another occasion, when she was arrested by police at Israel's Ben Gurion airport on suspicion of smuggling, a travel journal and letters by Kafka were found in her bag.

Israel's state archive was later allowed to catalogue Hoffe's collection, yet suspicion remained that she had hidden away the most valuable portions of it. It was not until her death two years ago, at the age of 101, that the battle for ownership of the lost Kafka archive began in earnest. Hoffe's two daughters, Eva and Ruth, claim to be the rightful inheritors of the documents, which, following their mother's death, were put in safe-deposit boxes – five in Israel and one in Zürich.

But they have incensed many in Israel with their talk of removing some of the papers from the country and selling them to Germany's Marbach archive (where they argue they would be better looked after).

Israel – which regards Kafka's legacy as a national treasure and a key to a lost way of pre-Holocaust European Jewish life – is furious. The national library is leading a court action against the Hoffe daughters that claims that the documents are the property of the state of Israel because Brod emigrated there in 1939.

It is contesting the daughters' claim and has been fighting ever since Esther Hoffe's death to be allowed to open the boxes in order to establish exactly what is inside them. The two women counter that they are being subjected to a campaign of vilification within Israel.

"I cannot believe how this country is behaving. It has no right to intrude," 75-year-old Eva complained in an interview earlier this year. She argues that if the papers are made public, her "property, assets , rights privacy and human dignity" will be compromised.

While the Israelis charge that the Hoffes are gold-diggers out to make a quick fortune from the Kafka manuscripts, the sisters insist that Israel is simply not the right place to keep the documents. "We have other things to do. We have terror and the fight for survival," maintains Eva. "Sorry, but culture is not first on the list. In Israel there is no place to keep the papers so well as in Germany."

Israel's academics think otherwise. They point to the fact that Kafka is part of the national school curriculum and that the writer's works are constantly put on as plays at theatres in an attempt to bring Israelis closer to a lost European past.

"Franz Kafka is a key figure," says Professor Dov Kulka of Jerusalem's Hebrew University. "Israelis are looking back to their European and Middle Eastern roots. He belongs to the intellectual map of Israel," he maintains.

The arguments used by Israel's national library to reinforce the country's claim to the Kafka documents are even more forceful. Meir Heller, the lawyer who is representing the library in the legal dispute over the documents, insists that Kafka's own diaries, which show that the author studied Hebrew, contain evidence that the author dreamt of emigrating to Palestine. "He had a dream of coming to Tel Aviv and opening up a restaurant," Mr Heller said. "He wanted to be a waiter. Kafka was no ordinary fellow."

Yet more than 80 years after they were written, the legal battle for Kafka's unpublished documents may only have just begun.

Last week Israeli experts who perused the Kafka documents lying in a Tel Aviv bank vault were confronted by an angry Eva Hoffe shouting: "It's mine, it's mine," and attempting – albeit in vain – to keep the vault shut.

Ultimately, Israeli judges will decide whether the documents should be returned to their deposit boxes or be published for the benefit of future generations. But before that, the courts have to rule on whether the Hoffe sisters' demands that the contents of the deposit boxes must stay secret should be upheld. No doubt Kafka would have loved it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments