Summer reading just got smarter

Discerning critics used to sneer at holiday bestsellers. But this year's Big Beach Reads are also works of literary merit, argues Boyd Tonkin. So is popular fiction wising up at last?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Opinions differ as to whether the coalition plans to return us to the Eighties. What's indisputable is that the bestselling author in its ranks has shifted millions of books by staying loyal to the values and ambitions often thought to define the Thatcher years. Louise Bagshawe, since May the Conservative MP for Corby and East Northants, shone on the shelves thanks to a series of steamy romances, from Career Girls through Glamour, Glitz, Sparkles and Passion.

Her books cleverly blended chick-lit and bonkbuster as they sent can-do heroines on upwardly mobile quests for success in boardroom and bedroom, rewarded by big-ticket, designer lifestyles. Desire, a new novel which bolts the raunch and bling of the Bagshawe formula on to an international spy romp, appeared just three weeks before the election. That might have caused concern to some in her party if the author had ever pretended to be Ann Widdecombe. To her credit, she never for a moment has.

Bagshawe still sells well, as do the kind of novelists who fashioned the genres she combines: the bed-hopping, star-studded imbroglio à la Jackie Collins, or the luxury-brand feuding- family saga in the manner of Penny Vincenzi. However, this style of summer blockbuster increasingly looks as much of a period piece as a Dynasty-era coiffure or a Norman Tebbit speech.

The Big Beach Read has changed. It has grown a bit smarter, and a bit deeper. Pure escapism has given way to a more solid grounding in character, history and even social reality. Wising up, rather than dumbing down, has marked the evolution of premier-league popular fiction over the past two decades. Once, the critically lauded Booker winner and the must-read chunky paperback epic axiomatically belonged in separate literary galaxies. No longer. Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall, already one of the prize's highest-grossing victors, has since its paperback release in March added another quarter-million to its UK sales.

Meanwhile, with aggregate paperback volumes of around 2m copies in this country already, Stieg Larsson's "Millennium" trilogy has gloriously torn up the mental script that used to keep commercial publishers inside their boring comfort zones. A dead author; a dead Swedish author, in translation; three long, involved political mysteries with a bisexual, feminist computer geek, a campaigning left-wing editor, and lots of earnest discussion about the corruption of the welfare state. Larsson was sui generis. But the global phenomenon proves that no source and no subject is off limits nowadays for the top-rating summer smash.

Of course, there will never be a uniform swing. Holiday suitcases or garden tables will still groan with copies of safe, generic warhorses. Old favourites who ran strongly in the UK paperback charts for the first six months of 2010 include crime and thriller stalwarts such as Lee Child and Martina Cole, doyenne of romance Danielle Steel and chick-lit diva Sophie Kinsella. And, still undead in a whey-faced world of their own, Stephenie Meyer's teen-vampire slabs occupied most of the Top 10 slots not taken by Stieg Larsson.

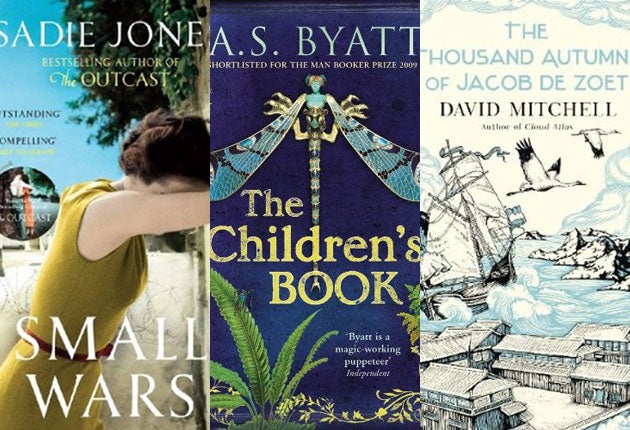

However, that particular chart – dominated by the reprints that still give the bulk of readers their first access to new fiction – captures the trend of the times. It exhibits a diversity much wider than the wall-to-wall pulp that characterised some recent low points in mass-market publishing. Wolf Hall, of course, reaches the Top 10, but Sarah Waters' The Little Stranger almost sneaks into the Top 20. John Grisham's latest courtroom cliffhanger is outsold not only by another translated author, Carlos Ruiz Zafon with The Angel's Game, but – for instance – by the erudite and panoramic Edwardian family drama of AS Byatt's The Children's Book. Mantel, Waters, Byatt: three Man Booker 2009 short-list titles, riding high in the cumulative charts.

Nick Hornby, Marina Lewycka, Cormac McCarthy (via a movie tie-in edition of the The Road) – all join the Booker contenders as the type of writer, selling well into six figures, who can not only give the genre "brands" a run for their money but leave them in the dust.

Strong individual voices can, and will, often outgun populist potboilers. Don't expect to see multiple dog-eared copies of Proust or Kafka lying around a Cornish café or Greek taverna soon – though who would ever have predicted the vast sales achieved by Penguin's new translation (by Michael Hofmann) of Hans Fallada's 1947 novel of small-time resistance to the Third Reich, Alone in Berlin? Still, the braining-up of bestsellers means that the range of books that can break out of the reservation of "literary fiction" and cause a bigger splash has substantially increased. Why, in a culture where the lowest common denominator so often wins the ratings game, has a contradictory movement taken place in bookselling?

Pessimists might argue that since fewer people read anyway, the market for truly trashy fiction has in part migrated to the computer-games console, the multi-channel TV and Facebook. Only brighter readers stay faithful to print. In fact, fiction sales have held up well in this recession: down only 1 per cent in the first half of 2010. And it could be that, among relatively light readers rather than dedicated bookworms, standards of taste and curiosity have risen. Has anyone studied the correlation between the steep ascent in the percentage of graduates in the population – especially among women – and the ability of more demanding fiction to make a louder noise?

Open-minded readers also have access to extra sources of information about books. TV book clubs, local reading groups, internet reviews, online retailing and so on join the traditional news-bringers, the quality press, libraries, bookshops. Marketing campaigns will display in lights books once consigned to the cognoscenti's ghetto; it was bizarre, but bracing, to see station posters for Alone in Berlin. And one promotional platform need not cancel or replace another. Harmony among the recommendations across various media can create an accelerator effect that pushes a book past the tipping point that separates cult renown from mass impact.

Two other factors favour the rise of the intelligent blockbuster. First, many gifted "literary" authors have rediscovered the old-fashioned virtues of rip-roaring narrative. The situation evoked by Tom Wolfe in his 1970s essays on the "New Journalism" – in which navel-gazing modern novelists disappeared up their own existential intertextuality while intrepid, clear-eyed reporters took on the mantle of a Dickens or a Balzac – now sounds dated indeed.

This summer, many fans will retire to sofa or sun-lounger with David Mitchell's virtuoso historical yarn of the Dutch in Japan, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet. Mitchell, the ultimate avant-garde crowd-pleaser, always cracks along with a page-riffling brio what- ever smart stunts he pulls in terms of style, voice and perspective. Wolf Hall marries the psychological depth and political nous of the serious novel of power and place with a gleeful willingness to adopt, adapt and subvert the Tudor court melodrama. Secondly, even those authors who consciously target their books at the broad commercial marketplace will now often do so with an eye on added value. Take the historical saga, which in recent years has seen several top-selling authors treat that adjective with a measure of respect that their forebears often forgot in the hunt for vague splashes of period colour.

The Return, Victoria Hislop's second chart-topping novel, repeated the ruse of her first as it led an under-informed British holidaymaker deeper into the past of the tourist trap she visited. Moving from Greece (in The Island) to southern Spain, Hislop opened a narrative trap door under her romance plot, and so plunged readers into carefully researched accounts of the upheavals of the Civil War of the late 1930s.

A historical bestseller such as Philippa Gregory – whose Wars of the Roses novel The White Queen figured in the paperback Top 20 for the first half of this year – knows that her clued-up fan base insists on authenticity as well as adventure. If many popular writers now aim rather higher than before, that might be in part because much of their readership has – contrary to the doom-sayers' mythology – grown in discernment.

Indeed, a female author's oblique angle on the horrors of war often seems to drive today's model of the up-market blockbuster. This is, if not history from below, then history from one side, as the plight of women and families swept up in the bloody tide of great events moves from the margins to the centre of the story. Writers such as Sadie Jones, with her novel of confusion and carnage in Fifties Cyprus, Small Wars, have proved the appeal of such tales.

This summer sees an especially rich crop of intelligent popular novels blown in some way by the winds of war. Lisa Hilton (a historian making her fiction debut) summons up the spirit of the French Resistance in The House with Blue Shutters; Lucretia Grindle revisits life and death among the Italian partisans in Tuscany in The Villa Triste. Further afield, and at epic length, Meira Chand follows three families through the tumultuous mid-century of Singapore in A Different Sky, and Julie Orringer shows Hungary's Jewish community menaced by genocide in The Invisible Bridge. Elsewhere, Kathryn Stockett brings the fledgling US civil-rights activism of the early Sixties into the parlours and porches of Mississippi in The Help – already one of the runaway successes of the season.

Any of these books might qualify as a meaty summer treat. All expect, and reward, a willingness to engage with the drama and trauma of the past in a way that the cheerful beach-bag sensations of yesterday very seldom did. And even those popular favourites which stick to the domestic sphere will frequently propel their plots with the fuel of a thought-provoking ethical dilemma. Mistress of this terrain is Jodi Picoult, whose novels of momentous decisions on the home front tend – even on their covers – to buttonhole readers with a Moral Maze-style challenge. "Five years ago, you gave birth to conjoined twins. You love both equally, but now only one can live. How do you choose?" (Yes, I exaggerate – but not by very much.)

Inevitably, travellers at any station, motorway or airport bookstall will notice that in many corners of the book trade the climate has not changed that much. Routine mediocrity certainly still thrives if it fits the right niche or carries the right name. Many retailers' hopes hang just now on the paperback of Dan Brown's The Lost Symbol, released last week. His preposterous Masonic hokum will over the coming weeks outsell not just superior "literary" fiction, but more uplifting contributions to the mass market as well.

Look out instead for the paperback of Stone's Fall by Iain Pears, a period epic of scandal and skullduggery in the business world of a century ago by a writer of zest and heft who straddles the divide between "brows" in a typically 21st-century way.

As he tracks his tycoon hero back from 1909 through his murky career in finance and armaments, Pears shows that a richly imagined modern blockbuster can indeed ask searching questions about our enduring debt to the values of the Eighties. The 1880s, that is.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments