Streets ahead: William B Helmreich has walked every block in New York - and stumbled upon incredible stories along the way

Over four years, covering 1,500 miles a year, Helmreich went in search of the heart and soul of the vast and variegated metropolis

Over four years, at 1,500 miles a year, I strolled, as a flâneur, through what is perhaps the world's greatest outdoor museum. The goal was to find the heart and soul of this vast and variegated metropolis by exploring all of New York City's boroughs: the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and of course, Manhattan.

Dressed inconspicuously – in khaki or grey shorts, black walking shoes, grey or brown T-shirt (no gang colours) – I covered almost every block in Gotham. Had I not done so, I would have missed a great deal: a man walking in Bushwick, Brooklyn, accompanied by four pit bulls, with two boa constrictors loosely coiled around his neck; the West Bronx church advertising exorcisms every Friday night at 7.30pm; the city's unknown, most gorgeous natural waterfall, tucked away in an impoverished neighbourhood; and much, much more.

When I was nine years old my father devised a game to keep me entertained. It was called 'Last Stop'. We lived on Manhattan's Upper West Side. Whenever he was free on the weekend, we walked to the local 103rd Street stop on the IND (Independent Subway System) line. From that subway we would transfer to another train and take that to the last stop on the line. Upon exiting we would explore the neighbourhood on foot for a couple of hours, sometimes taking a city bus to further extend our trip. When we ran out of last stops on the various lines, we'd move the destination point to the third-to-last or some other stop. We played this game off and on for about five years, until I began high school.

That's how I learnt to love and appreciate New York City. I would stand with my father, looking out on the marshes that were in Brooklyn's Canarsie section, and reflect, "So this is where my teacher told me he'd send me if I misbehaved". One time my father poked his head into a bar near Utica Avenue in Brooklyn and everyone scattered. I never found out why. Another time we took a bus to the Throgs Neck neighbourhood in the Bronx, and I saw men fishing. I marvelled at the sight, having never before seen anyone fish. I was a city kid. I played in the streets, belonged to what passed for a gang on my block, and knew every chocolate bar in my local sweet shop. These experiences and the trips I took were the fertile ground where the idea for a book on walking around New York grew. As for my father, he continued walking well into his eighties, extolling its health benefits. He died of natural causes in 2011, three weeks shy of his 102nd birthday, so I guess he was right.

Walking New York City, block by block, brought into sharp focus a reality that I always knew was there but had never really articulated, because it was so much a part of me that I never felt a need to express it. It emerged time and time again as I spoke and interacted with people from every walk of life. To sum it up, New York is a city with a dynamic, diverse, and amazingly rich collection of people and villages whose members display both small-town values and a high degree of sophistication. This stems from living in a very modern, technologically advanced, and world-class city that is the epitome of the 21st century. That is both the major theme and conclusion of my intense and detailed journey to every corner of the Big Apple.

Ask someone who lives in the outer boroughs if they consider themselves New Yorkers, and the answer will almost always be a resounding yes. After all, isn't the city defined as five boroughs? And aren't they only 30 minutes to an hour away from Manhattan? These realities do contribute to a sense of oneness among people wherever they reside.

New York City has more legal immigrants and children of immigrants than any other city in the world, with almost 700,000 new immigrants arriving in the past decade alone. Together they make up a majority of the 8.3 million people living in the city, with most of them coming from the Dominican Republic, China, Jamaica, Mexico, Guyana, Ecuador, Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, Colombia, Russia, India and Korea, along with those from Puerto Rico, who have a unique status as citizens, plus an estimated half-million-plus undocumented residents.

Walking on 124th Street in East Harlem, I came across a remarkable mural that covers six storeys of a tenement building wall. Called Centro de La Paz (Centre for Peace), the mural was sponsored by the Creative Arts Workshop and painted by more than 200 New Yorkers, many of them poor neighbourhood youngsters. Their efforts were augmented by some 100 artists from around the world – Argentina, Ecuador, Nigeria, England, and elsewhere. The names of the artists are duly inscribed on a two-storey-high scroll that is part of the mural. It features skyscrapers, igloos, pyramids, and the Grand Canyon.

In a city with hundreds of murals, this one definitely stands out – in scope, design, beauty, and size. The many immigrant groups depicted and the themes of unity, diversity, and tolerance encompass the aspirations and hopes of the millions of immigrants who have come to New York City since its inception and who have shaped it into one of the greatest cities in the world.f

Impressive as this undertaking is, the immigrant experience can also be captured in individual stories. They look to the future but release their hold on the past with reluctance, because it is, and always will be, an essential part of their lives. That bifurcation is clearly brought home to me one day as I walk a street in Jamaica, Queens, and spy a man on a quiet block. He has created a beautiful garden along the grassy strip that runs next to the gutter. It's a small area, about four feet long and three feet wide, surrounded by a miniature white picket fence.

"These flowers are beautiful," I say by way of starting a conversation.

Small and wiry, with bright white teeth framed in part by a neat moustache, he responds with a soft smile: "They are flowers from my country, Guyana, which I love. I planted them to remind me of home. This way, when I look outside I always remember the beautiful place I lived in before I came here."

There's no way to know how many of the city's immigrants have used their gardens for similar purposes, but it's unlikely he's the only one. In this vignette it is apparent that home is never far from the thoughts of the immigrants. And is this any different from earlier generations of Italians who planted fig trees in their gardens that went under wraps every winter?

One of the biggest stories here in recent decades has been the gentrification of large swathes of New York City. The past 25 years have seen a large population shift as hundreds of thousands of young people have streamed back to the city that their parents abandoned. In this they have been augmented by large numbers of gentrifiers from all over the country.

Both groups have been attracted by the opportunities in the Big Apple as it has shifted from an industrial to a service economy. Coming at first as single, unattached adults, in recent years young people have been putting down roots, deciding more often than not that they want those roots to be in the inner city. And although low-income residents can be found in all five boroughs of New York City, this drift toward city living is part of a larger trend in which the poor are increasingly found in the city's outskirts and suburbs.

One tends to think of places like Manhattan's Tribeca or SoHo, or Brooklyn's Park Slope, as representative of this trend, and they are. Yet nowhere is the shift more apparent than in Harlem which has gone from an overwhelmingly black community to one that is almost 50 per cent white. To discover dramatic change one need go no further than Harlem's Bradhurst Avenue, now called WEB Dubois Avenue (after the civil rights activist), which extends from 145th Street to the Polo Grounds projects by 155th Street. Until the mid-1990s, Bradhurst Avenue was one of Harlem's most notorious locations for drug dealing and crime in general. Jackie Robinson Park, which runs along the avenue, was considered unsafe at any time of day or night.

Today it's a new world. On the corner of 145th and Bradhurst you have the luxury condominium called the Langston, after the poet Langston Hughes. This is followed by the Sutton, named for the Harlem political leader and former Manhattan borough president Percy Sutton. Next to it sits the Ellington, in memory of jazz icon Duke Ellington. You can now walk the length of Bradhurst Avenue in complete safety, even at night, though somewhat less so because of the projects at the north end, whose residents must look upon the street with envy – so close, yet so far away in terms of what they can afford.

Here are the words of Don, a maintenance worker at one of these buildings. Balding and dressed in a red-and-grey-checked flannel shirt, with owlish gold-rimmed glasses, he greeted me with a firm handshake. I had found him in the boiler room after someone in the building told me that he was the "neighbourhood expert". When I told him I was trying to understand the Bradhurst area now as compared to the past, he stared at me intently, like a man with something on his mind. He's a bouncy sort of guy, and he frequently punctuated his responses by jumping off the bench where he was sitting and describing, with windmill-like motions, how things had changed over time. I soon learnt graphically what Bradhurst used to be like in the "bad old days".

"Let me tell you somethin'. These apartments go from $300,000 [£187,000] to more than $400,000 [£249,000]. They got condos and co-ops. They got all sorts of stuff here. But one time, damn it, in June of 2010, they told me there's maggots here; you know, they feed on human flesh. I went to look at them and there must have been a half million maggots comin' up out of the ground, through cracks in the sidewalk. I don't know where the fuck they came from. When they came here to build and knocked down them old buildings – I swear to you I am not exaggeratin' – they knocked some of these walls down in the tenements here, and they discovered bodies in the walls. People had been buried here for years.

"And some of them was there because of Preacher [Clarence Heatley], the drug dealer, who ran this place. He'd say, 'I like this car' and you'd have to give it to him. If not, you could end up dead ... He controlled this state. All the drug dealers were afraid of him. He'd say, 'Give me money'. They'd have to give him money."

"So how did crack die here?" I ask.

"People just got tired of the crack. The crack epidemic started in Los Angeles in South Central and it came back east. That started all the wars. So many people got strung out. And then they just got tired of being drugged out and not havin' any money."

"Is Harlem becoming more white?"

"White? I call this area above 145th Street West [Greenwich] Village! You got white people, yuppies moving in here. All the prejudiced people, they died out. These yuppies don't give a shit. They just wanna get to their jobs. People get tired of having to have two-fare zones and everythin' else. Nobody wants that shit. So that's how the neighbourhood completely changed. This is now a very interestin' neighbourhood. And it's a lot safer now than it was before. Actually, in the early Seventies Bradhurst was a very nice area. Then came the crack epidemic and it all changed. Now it's back to where it was before."

With an annual murder rate (414 killings in 2012) that has dropped dramatically since 1992, New York has become the safest big city in the US. The immigrants have been welcomed, assisted, and are, by and large, adapting rather well. The city has been profoundly affected by 9/11, but it has rebounded extraordinarily well from the tragedy.

Gentrification has clearly invigorated the city. Yet beautiful as formerly poorer parts of New York City like Harlem or Bedford-Stuyvesant might look today, there is a concern that a world-class progressive city worthy of the name cannot consider itself a success if it fails to attend to the needs of its less fortunate residents. There are still plenty of poor people in this city, clustered in various areas like South Jamaica, Melrose, Brownsville, Manhattan's Alphabet City section of the Lower East Side, and portions of Staten Island's northern area. They need to be helped, according to this line of thinking, and both government and the private sector must do more to provide a safety net for the poor by creating more affordable housing, jobs programmes, and better municipal services.

It's when you walk the streets of, say, Brooklyn's East New York and Brownsville sections that you begin to see how much remains to be accomplished. There are miles and miles of 100-year-old tenements that didn't look good even when they were first built a century ago. Young toughs glare at strangers, standing on streets littered with broken bottles, empty grocery bags, and other debris. The scene is one of desolation, all within a 35-minute train ride from Manhattan's Disneyfied Times Square.

This is equally true of the Bronx, again a half-hour ride from the city's centre. My conversation with a poor resident of the Jackson Houses in the South Bronx sums it up rather well:

"Is the neighbourhood safe?"

"No, there's crime here all the time and it's gettin' worse."

"Are you aware that we went from close to 2,500 murders a year in the early 1990s to less than 500 last year? That's an 80 per cent drop."

"Oh, yeah? Well, let me tell you something, mister: if there's 500 murders a year now, then 400 of them is happening right outside my window."E

'The New York Nobody Knows: Walking 6,000 Miles in the City' by William B Helmreich is out now (£19.95, Princeton Press)

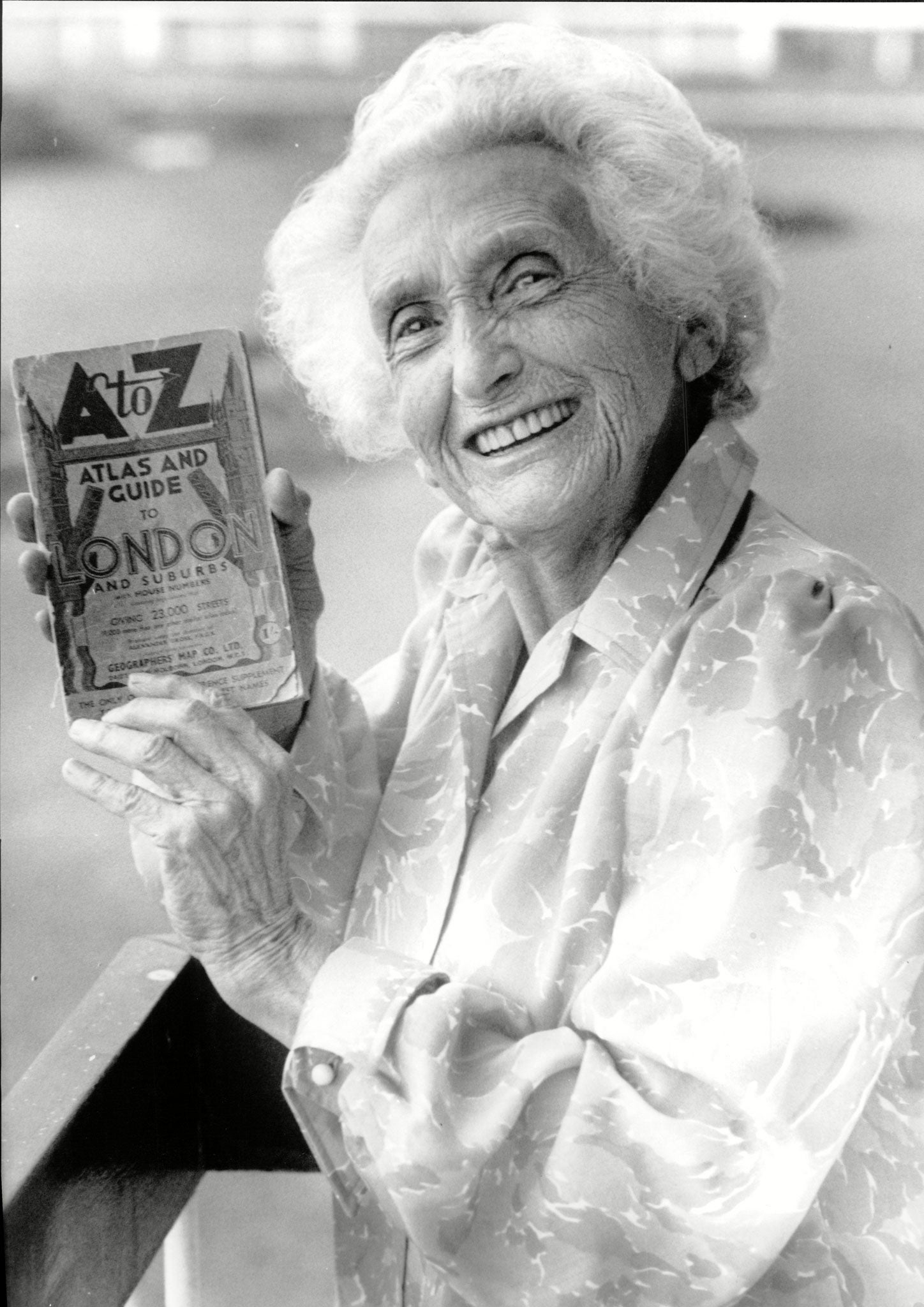

The woman who walked London

Tirelessly traversing the streets of a city is not just the preserve of male strollers such as William Helmreich – we have a pioneering woman to thank for the original London A-Z. Phyllis Pearsall, in 1935, mapped the streets of the capital on foot, after she got hopelessly lost one soggy night trying to find a party with an out-of-date map. Legend has it, she would rise at 5am to walk the 3,000 miles of London's 23,000 roads, often working 18-hour days.

Her map had almost as far to travel before it reached the public. No one wanted to publish, so Pearsall founded her own Geographers' A-Z Map Company to print The A-Z Atlas and Guide to London and Suburbs in 1936. She hawked her hard-won wares round retailers; eventually, WH Smith bought 250, on the guarantee they'd get a refund if the copies didn't shift. But the A-Z was an instant hit. Aside from during the Second World War – when map-selling was a no-no – it's been in continuous publication since.

Pearsall's aim was to make it user-friendly, and the straightforward indexing system gave the map its name. She cheated the look, so streets appear proportionally larger than they actually are – and therefore easier to find and follow.

Mapping was in the family: her father, Alexander Gross, was a Hungarian cartographer. Born in 1906, she attended Roedean School for Girls – until her father was declared bankrupt and fled to America. When she returned to London, after a spell in Paris, in 1935, it was as an artist she considered herself, until her death in 1996. The map was only ever supposed to help fund a painterly existence – even if it is today considered a design classic.

By Holly Williams

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments