Stephen May: 'My stories say things that are not being said'

Stephen May speaks about shambolic men, a misspent youth, and his third novel

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

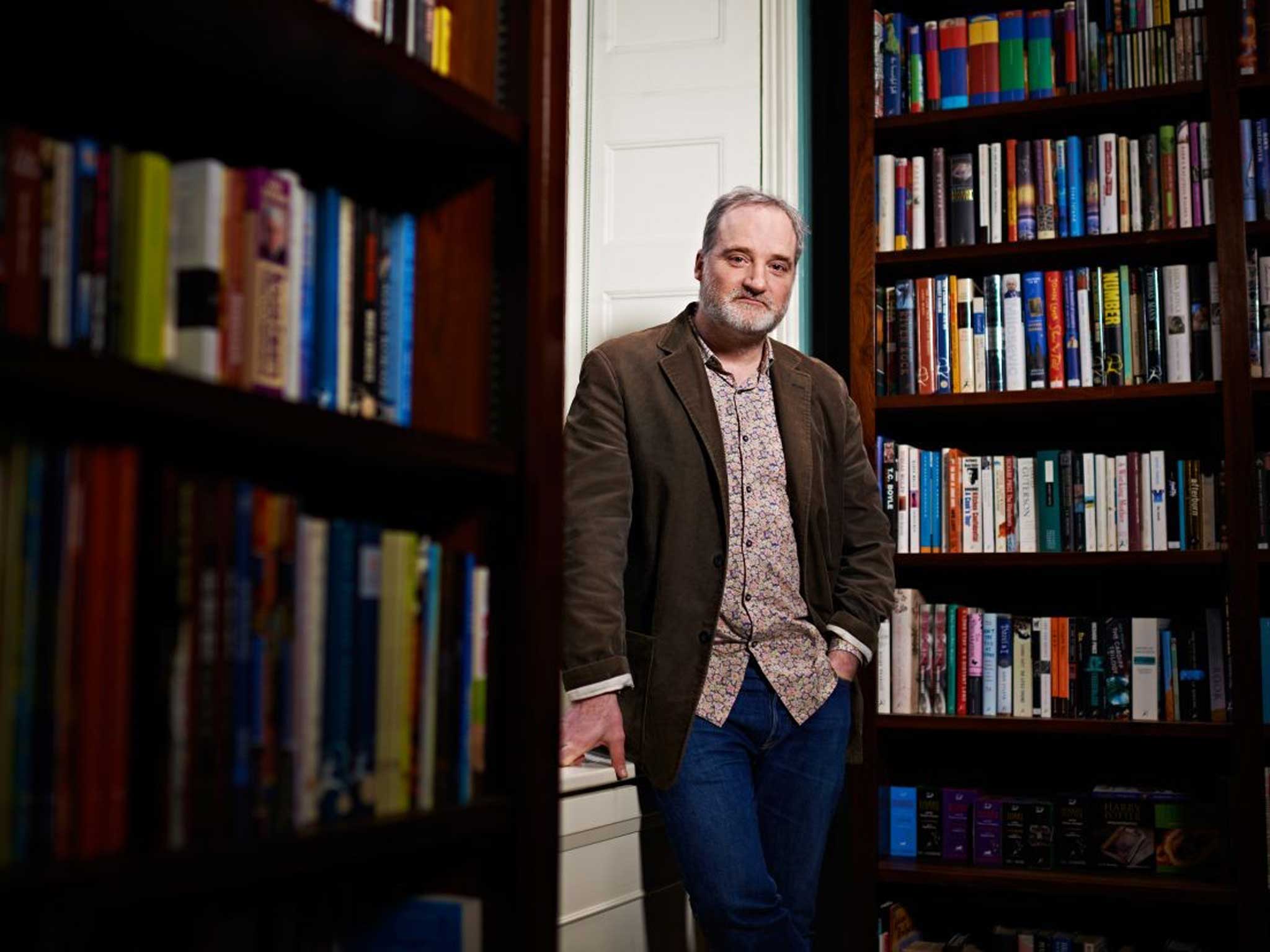

Your support makes all the difference.You’re probably unable to tell from the photograph but this morning Stephen May suffered the kind of mishap that might befall the men who populate his fiction. “I was trimming my beard,” he explains, as we walk through Bloomsbury in the chilly February rain. “The battery conked out on my razor. I’ve left the charger at home in Yorkshire so I’ve had half a shave.” I point out that at least he, unlike me, was sensible enough to wear a coat and we make a dishevelled pair as we arrive at an empty pub, a few minutes after opening time.

“This is a rare excursion for me,” says May, ordering beer. “For the first 10 years of my adulthood, I drank too much and ran around too much.” This was after leaving school with five grade “U” O-levels but, although he riffs entertainingly on failure (“Who wants to get Ds?”), I’m suspicious of May’s slacker shtick. His new novel, Wake Up Happy Every Day, is his third in six years, after his debut, TAG (2008), and Life! Death! Prizes! (2012), which was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award. He’s a late-starter when it comes to writing but he was always a precocious reader and, during our conversation, quotes Jane Austen, Gustave Flaubert and Franz Kafka. Is he exaggerating his former fecklessness? “I wasted so much time. But I’m not unambitious and what looked like spectacular under-achievement turns out to be material because I write about under-achievers. It’s a writer’s job to pay attention to things other people miss.”

Life! Death! Prizes! was narrated by Billy, a mixed-up teenager, struggling to raise his little brother after the death of their mother. It earned May comparisons to Dave Eggers and J D Salinger but, even though most of Wake Up Happy Every Day is set in San Francisco, his heart remains in England. “Nicky is a small-town boy in America,” he says of his new novel’s main character, who is, like May, 50. “This country’s spirit is in places like Bedford, where I grew up, Kettering and Ipswich. The type of men I write about live outside big cities, lack self-confidence and rarely feature in contemporary fiction. Even Nick Hornby’s characters are more sorted than mine.”

May says “sorted” as though the word represents an unobtainable state for him and his characters. He was visiting his “very sorted” daughter while she was studying at Berkeley University when he chose his American setting: “I expected to hate California but I loved it.”

Along with his wife, Sarah, and infant daughter, Scarlett, Nicky is staying in San Francisco with Russell, his multi-millionaire best friend. When Russell drops dead, Sarah helps Nicky pass the death off as his own, assume Russell’s identity and enjoy the fortune they believe will bring them happiness. “It’s not the most plausible aspect of the plot,” May admits, “but I reckon today it’s easier than ever to steal somebody’s identity.” Nicky undergoes a makeover so that he can impersonate an alpha male plutocrat but, although Sarah likes his six-pack, their champagne lifestyle loses its sparkle. They notice that the rich rarely laugh and money makes life predictable.

“When I’ve been around wealthy people they’ve seemed to lead quite restricted lives,” says May. I highlight the gulf between his characters’ thoughts and what they say out loud and he says: “We all hold convictions which we daren’t express. My male characters struggle to be kind against their darker instincts. The women are decisive and just plain nicer. I know the men annoy some people. My daughter, who didn’t like my second novel, said: ‘I’ve met boys like Billy and they’re fucking annoying’.” I sympathise with May’s daughter, up to a point. Initially, I found Nicky’s everyman persona grating, average and incurious, but once he’d developed some guts and imagination, I cared about him.

While May’s characters rein in their opinions, he has plenty to say in his books and in person. Having spent his 30s teaching, he’s angry about government education policy: “The Tory attitude is: ‘Our kids can do creative stuff but your kids will be stacking shelves’. It’s absolutely shocking.” He still teaches creative writing and co-wrote a guide to the subject, so what did he make of Hanif Kureishi’s recent remarks about “waste of time” courses? “A teacher who says – as Hanif does – ‘fuck the prose, think about your story’ is helpful. Writers can find mentors on library shelves but being among supportive, competitive students is nurturing.”

Teaching, raising three children and working for the Arts Council exposes May to various generations and idioms. His characters share his disdain for everyday bullshit and Russell’s estranged daughter Lorna’s repartee with her roommate is as convincing as the touching story of Nicky’s old dad back in Blighty. “I wanted to create a range of voices,” May says, “to tackle themes of friendship and money. Nicky and Sarah expect to have fun with Russell’s cash but many of us would be embarrassed by vast wealth. It would disrupt your ordinary interactions and relationships. I’ve read that the joy you feel on receiving £30,000 is the same as if you receive £1m.”

With Lorna growing suspicious, Nicky is in danger of being rumbled as an impostor but his problems escalate when an assassin, who’s both sinister and comical, is dispatched to eliminate him. “She’s based on somebody I met on a children’s writing course,” says May. “Students were asked to reveal something surprising and she said: ‘I could kill you all with my bare hands’.” Is he wise to reveal this? Isn’t he concerned that this aspiring J K Rowling will track him down? “I’m more worried that Nicky’s views about the cake habits of women in offices will land me in trouble. But I think I need to toughen up.”

I’m not so sure. Talk of misspent youth, assassins and obstreperous protagonists belies the emotional core which makes May’s books moving. “In some ways, having children saved my life,” he says, when I suggest that Scarlett represents her parents’ best hope of happiness. “With them came a safety net of responsibility that stopped me destroying myself. I agree with Flaubert that you should ‘be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work’.” Does writing make him happy? “In a sense all books fail. They’re never as good as they could be but this weird compulsion to express myself gets more urgent with age. I need to tell stories and say things that aren’t being said.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments