Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

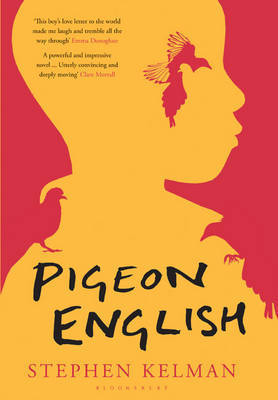

Your support makes all the difference.A few weeks ago, Stephen Kelman fell off a slide and bumped his head. It was hardly the ideal preparation for the publication of his eagerly awaited second novel, which follows his Man Booker Prize-shortlisted debut, Pigeon English (2011). As he observes with characteristic self-deprecation, it’s not the kind of injury you can imagine, say, Ernest Hemingway sustaining. But it pales, too, in comparison with the exploits of Bibhuti Nayak, the main character in Man on Fire. Bibhuti is based on a real-life martial artist of the same name, who holds world records for feats of endurance, which include completing 114 fingertip push-ups in one minute, 1,448 stomach crunches in an hour, and breaking concrete slabs against his groin. Why, then, did Kelman decide to write about him?

“I first saw Bibhuti,” he says, “when he was being kicked in the nuts by Paul Merton in a documentary about India. For many people, Bibhuti would be a figure of fun but he has a singular story and I wanted to explore the dignity within him.” Bibhuti was delighted by Kelman’s plans to tell his story and they exchanged emails for two years. “He writes in a unique argot which bursts off the page, so that made my job easier.”

In 2010, Kelman visited Bibhuti and his family in Mumbai for the first time, witnessing his fitness regime which demands a vegetarian diet and only two hours’ sleep per night. Today, Kelman calls Bibhuti “my best friend” and the feeling is mutual.

We’re sitting in Kelman’s editor’s office where, tacked to the door, is a poster for Pigeon English. Has it been put up especially for our interview? “No, it’s always there, and so is that one,” says Kelman, pointing to another poster for the novel’s paperback edition. Pigeon English touched many people, so did Kelman feel under pressure when writing his second novel? “I wanted to repay the faith of my publishers and readers. My first novel’s Man Booker shortlisting and sales exceeded my wildest dreams”.

What did he make of the way some critics denounced the populist appeal of the 2011 Man Booker shortlist? “I don’t know how much of those criticisms were directed at me. I was an unwitting participant really. But the shortlisted authors developed camaraderie and viewed the furore as artificial, media-generated. The judges’ desire to promote quality literature that can appeal to a wide readership was a worthy one.”

In terms of setting and subject, Man on Fire is a departure for Kelman, who says: “I have no interest in returning to the world of my first novel.” He lives in St Albans with his wife, but regularly visits his parents on the Luton housing estate which he calls “a dead ringer” for the one where he set Pigeon English.

It was while growing up there that Kelman, who was born in 1976, decided he wanted to become a writer: “From the age of six, I was a prodigious reader. As a child, I didn’t understand most of Wuthering Heights and The Mill on the Floss but I knew I wanted to write stories. I kept writing but I studied marketing at university, in part because I had this rather high ideal that I’d find my voice as a writer in my own time.”

The freedom to write in other people’s voices excites Kelman and gives his prose its dynamism. Pigeon English was narrated by Harri Okupu, an 11-year-old Ghanaian boy, in a lively idiom which used terms such as “asweh” (I swear) and “hutious” (frightening) to articulate his sense of wonder. That said, it begins with a murder, which Harri tries to solve, and it ends in tragedy. Kelman agrees when I suggest that both his novels present decent people within corrupt societies: “Yes, I can’t help but feel outrage at the corruption that surrounds us.”

Having written from the perspectives of Ghanaian and Indian characters, Kelman’s comfortable adopting voices from other cultures: “I love slipping into the skin of another person when I’m writing. There were waves of immigration into Luton from the subcontinent and Africa, so I was raised alongside people from all over the world. There was a great mix of backgrounds and voices among my school friends.”

The other narrator of Man on Fire, John Lock, is a terminally ill Englishman who, after seeing Bibhuti on television, abandons his wife, fakes his own death, and travels to India. As a way of giving the end of his own life meaning, John wants to help Bibhuti with his most punishing world record attempt, which involves John breaking baseball bats over Bibhuti’s back. Kelman “struggled to find John’s character” and acknowledges that he’s a difficult narrator for the reader to get to know: “India opens John up and leads him to express things that he’s kept hidden. I wanted John to surprise the reader with his capacity to feel in a way that’s beautiful and melancholy. A deep, platonic love develops between John and Bibhuti.”

But why choose to be whacked with bats or kicked in the groin? Is an entry in the Guinness World Records book worth it? Bibhuti is extremely strong but I’m sceptical of his notion that “pain is a choice” because it sounds like the kind of hokum that permits indifference to suffering. Bibhuti, though, believes his feats are a source of inspiration for his countrymen who endure poverty and illness. “He wants to stamp his mark on history and John wants to create his own legacy by helping,” says Kelman. But do they, in pursuing their goals at the expense of all else, neglect the people closest to them? “Bibhuti loves his wife and son but he risks losing them. John is trying to achieve something fantastic in the time that he has left. With both narrators, I’m examining the tension between the obligation to live and the obligation to dream.”

Kelman is intrigued to see how readers respond to Man on Fire. “I want to discover new worlds and I’m asking the reader to go with me,” he says, although his most important reader has already given the novel his blessing: “After I emailed the manuscript to Bibhuti there were five days of silence before he replied: ‘Just finished. Can’t talk now. Too emotional.’ Eventually, he explained that he and his family had read the book together. He was delighted. If he hadn’t been, I would have reworked it, but Bibhuti’s approval now insulates me from other opinions. Many people won’t like this novel, they won’t believe it, but I’ve fulfilled my promise to Bibhuti. So I’m happy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments