Should smoking be banned from children's books?

Julia Donaldon's latest book has been criticised for having a scarecrow who smokes, but, says Philip Womack, children's literature shouldn't have to filter out bad habits

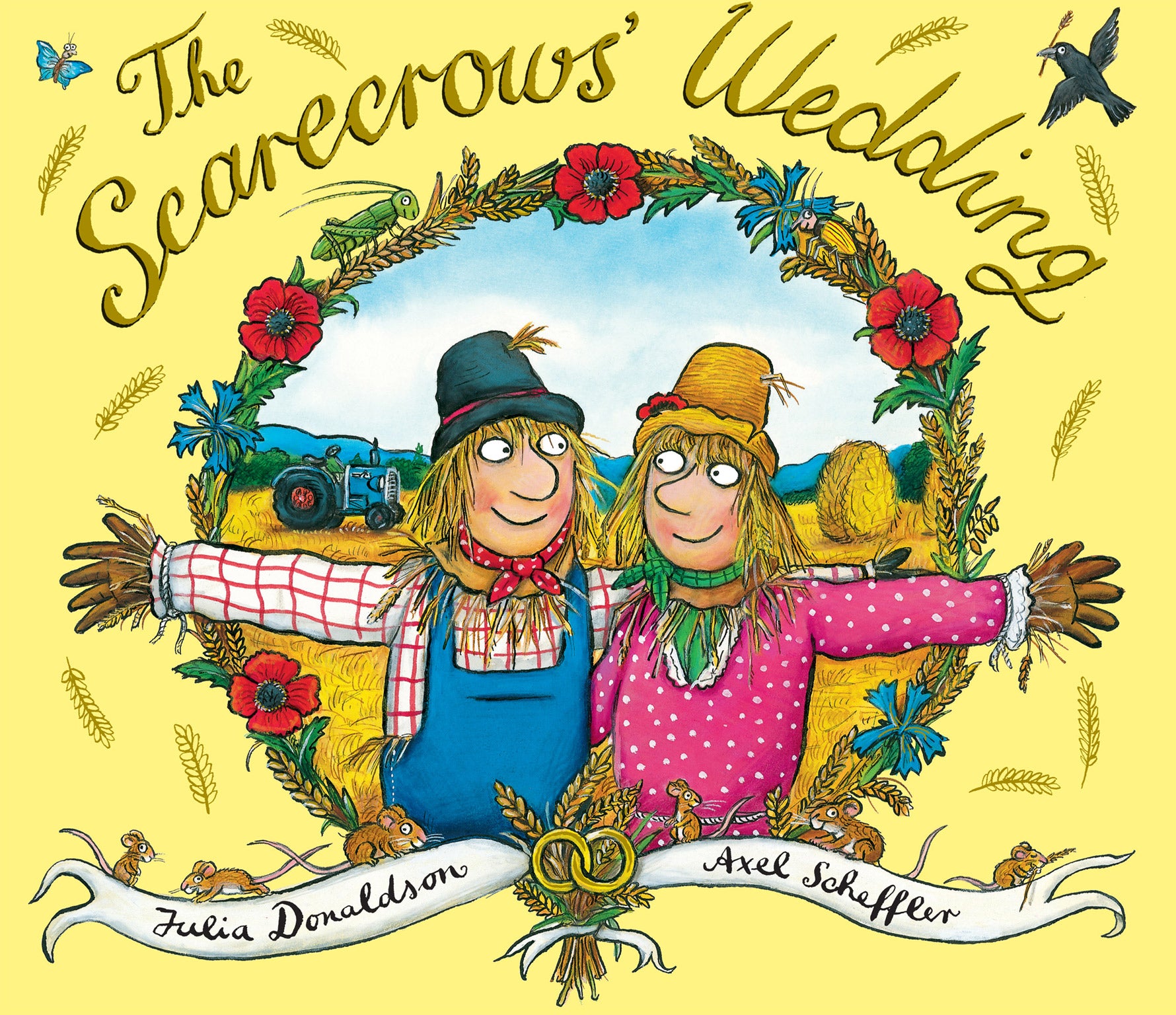

What is the function of a children's book? To entertain; to warn; to depict life, with licence to fantasise. In Julia Donaldson's new picture book, The Scarecrows' Wedding, Reginald Rake, a scarecrow, lights a cigar, and is immediately admonished; he then manages to set on fire the female scarecrow that he's courting. Cause and effect are clear: smoking harms you and those around you (although Rake gets off with only a cough). What could be more obvious, and less controversial?

And yet. This little plotline has this week drawn a good deal of, ahem, fire from commentators on the internet, who claim that even showing the idea of smoking in a children's book is wrong.

This misunderstands something fundamental about picture books. They are, first and foremost, fantasies. I don't see anyone complaining about the fact that the scarecrows can talk; nor that they are brought a necklace of shells by a handy crab when they are nowhere near the sea. A fantasy can be used to make a moral point, as Donaldson does, patently; and since children respond much more easily to ordered, made-up worlds than they do to the baffling real world, it is often the best way to get something across. Think of Aesop's Fables: morality encoded in talking animals.

Smoking has been considered wicked in public for so long that it's almost de rigeur for a villain to light up. Even as long ago as E Nesbit's Five Children And It, first published in 1900, when the children wish for their baby brother to grow up, he does, turning into a foul, smoking, sex-obsessed young adult. The message is clear.

Admittedly, this hasn't always been the case. The donnish wizards in J R R Tolkien's Lord of the Rings novels evidently enjoy smoking, as do their hobbit companions. The caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland is baked off his head on some kind of oriental substance. But to children these actions seem part of an alien space: they do not identify with the smoking caterpillar, still less wish to do the same (though they might enjoy pretending to do so).

Even if anyone did think these examples were bad, we cannot go back in time and erase all mentions of something that used to be part of everyday life.

The main reason that most people smoke is that someone else, in the real world, who is considered cool, smokes. Those who do it do so to feel included in an adult atmosphere – and, largely against the warnings constantly issued by parents, teachers, cigarette packets and governments alike. They don't do it because a naughty scarecrow sets fire to another with the ashes of his cigar in a book they read when they were two.

One of the anti-Donaldson commentators speculated about the dangers of unprotected sex being shown in children's books. Well – what about The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe? If that doesn't stand as a stark warning against the dangers of doing it without protection, or even doing it at all, then I don't know what does.

Children's books take the life that exists in manifold beauty and horror around us and distil it into a form that children can delight in, be frightened by, and, possibly, learn from. It is unfair, not to say pointless, to stem the creativity of a thriving area of literature by issuing puritanical edicts. Children's books expand and explain the world, and that means everything in it: smoking included.

'The Broken King' by Philip Womack (£6.99, Troika Books) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments