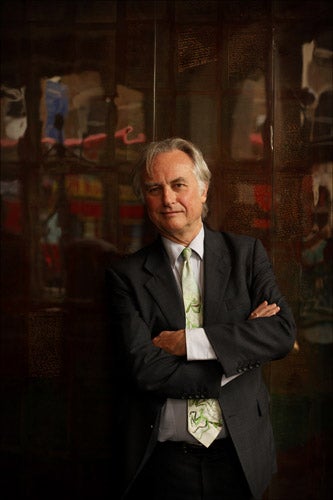

Richard Dawkins: 'Strident? Do they mean me?'

With his latest book, creationist-basher Richard Dawkins believes he has amassed all the evidence he could ever need to convince unbelievers that Darwin was right. Now he just has to get them to read it...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Richard Dawkins is in the middle of London's Natural History Museum, telling me about the applications on his iPhone. Sitting in the museum café, he holds the phone up to his mouth and tips back his head to show me how he can drink a virtual "pint" of Carling on screen, the beer draining as the phone tips further. Which is not exactly what I was expecting.

Dawkins has the enthusiasm of a teenage geek for new technology. "I love my iPhone," he confesses. "I'm on my third already." Then he shows me another phone app, this time simulating Darwinian natural selection. As each generation of a populace is born, the appearance of the group of individuals on screen varies. As Sir David Attenborough walks past and says hello, I feel secretly relieved we aren't still laughing at the lager trick. "Do you find it difficult to switch off from technology?" "Aha, yes," he says with a dark chuckle, straightaway. And do you ever get in trouble for that? He laughs again.

To most observers, Dawkins is the textbook aggressive champion of evolutionary theory. His new book, The Greatest Show on Earth, is intended to amass the scientific testimony for evolution in one place, answering creationist critics who say there is no evidence that evolution by natural selection has ever taken place. In person, Dawkins fails to live up to the "aggressive" label.

More rightly described as "dapper", he is today wearing a pale-grey suit whose stitching and cut look deliciously Savile Row. The smartness is tempered by a touch of English whimsy: the outfit is completed by a hand-painted tie featuring the birds of the Galapagos, with wings outstretched for flight, and talons spread to snatch prey. "My wife painted it for me," he explains proudly.

All in all, he is an intriguing combination. He has the beady-eyed, fiercely scrutinising gaze of the Oxford professor inviting you for interview, and at the same time a warm and generous enthusiasm for science and all its manifestations (including those of Steve Jobs and the Apple corporation). But his greatest wonder is reserved for the natural world.

Walking through the gallery that contains skull casts and bones from our ancestors, he greets each as if they were old friends. "Ah, dear boy!" he exclaims to one skeleton. (It turns out "Dear Boy" is the nickname given by celebrated anthropologists the Leakeys to Paranthropus boisei, a skeleton they carried around for a time in a biscuit tin. It is now recognised as one of our most distant relatives.)

Then, moments later, he says more sadly, "Ah, the Taung baby": a child snatched from its mother by eagles some 2.5 million years ago. The child died after having its eyes pecked out, as evidence from the skull shows. In his new book, Dawkins spends a whole chapter discussing human evolution, including a touching passage on the Taung baby and its bereft mother. It's this ability to be deeply imaginative that captures his readers in their millions. As we walk through a gallery hung with gibbon skeletons, articulated as they would be in their jungle home, he stops and sighs: "It must be a wonderful experience to swing your way through the forest like that, at extremely high speed. They actually take off for a moment when they swing from one branch to the next. Very much like flying," he adds, wistfully.

The Greatest Show on Earth tackles more controversial matters, too. Included is a transcript of his 2008 interview with Wendy Wright from Concerned Women for America, an out-and-out creationist who simply denies the existence of evidence for human evolution. As Dawkins urges her repeatedly to visit any museum and see the skulls and skeletons for herself, she simply ignores him and repeats her own orthodoxy. "Why is it so important to you that everyone believes in evolution?" she asks, almost plaintively. "I am a lover of truth," he simply tells me.

So he is genuinely puzzled by people calling him aggressive. "Well, I'm nothing like as aggressive as I'm portrayed. And I'm always being labelled 'strident'. In the bestseller lists it always has a little one-line summary of the book, and for my new one it says 'strident academic Richard Dawkins'. I'm forever saddled with this wretched adjective. I think I'm one of the most unstrident people in the world. I'd like to think my books are humorous at points," he adds, pensively. "I'd like to think people laugh when they read them."

There are moments in the new book which do make the reader laugh, not all of which concern Wendy Wright and her views about the morning-after pill ("a paedophile's best friend"). Dawkins quotes in full Eric Idle's Monty Python parody of "All Things Bright and Beautiful," a hymn he has clearly enjoyed seeing rewritten. His books also have whimsical moments: in this one, a full-page colour photograph of one biologist's naked back, bearing a large evolution-themed tattoo.

But most importantly his writing radiates an intense sense of fascination. He is a great explainer, taking complex biological processes and making them accessible. Here, that includes the development of the embryo in early pregnancy, the wonkiness of giraffe anatomy, and our own fishy ancestry.

Born in Africa during the Second World War, Dawkins had parents who were both keen naturalists – his father worked for the British government of Kenya, a biologist specialising in agriculture. Africa was an exotic environment for a small child. Walking around the insect gallery, he suddenly sees a large scorpion preserved in a mahogany case, its tail raised as if about to sting, and stands back. "I was badly stung by one of them as a child," he reveals. "I'm quite frightened of large spiders and scorpions still."

But young Dawkins also spent time in England. "My grandparents lived at Mullion in Cornwall, so we always used to go there for our holidays. It was idyllic." Holidaying at their home on the Lizard, he developed a lifelong passion for walking the cliff path. "All the way down from Mullion, past Kynance, to the Lizard," he says, with a smile. "Lovely flowers, sea pinks on the cliffs."

He has a clear sense of his debt to a series of inspiring mentors. An old headmaster at his school, called Sanderson, had been enormously enthusiastic about natural history. "And his spirit lived on there. My old biology teacher Ioan Thomas had come to the school specifically because of it. There was one time he came into class and asked: 'What animal feeds on hydra?' We didn't know. He went right around the whole class asking. Everybody was guessing, and then, finally, we said, 'Sir, Sir, what animal does?' And he waited and waited, and then he said, 'I don't know. And I don't think Mr Coulson does either.' He burst into the next room, got Mr Coulson and dragged him out by the arm, and he didn't know either! It was a wonderful lesson, I never forgot it and neither did anyone else: it's OK to not know the answer."

He is proud of his career so far: "All my books have sold very well, and none has ever gone out of print. The Selfish Gene has sold as many as The God Delusion, but over a longer time span, of course. My books do make a lot of money, and I don't want to keep it myself, so I wanted to find something to put the money into. I started my charitable foundation, The Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science, to promote a sceptical, critical, enlightened view of the world." So, I ask, you never splash out on anything? He pauses. "Actually we do have a swimming pool," he admits, bashfully.

He remains passionately interested in the world around him. At one point he stops in front of a display on dung beetles rolling up balls of faeces in their burrows. "I never knew they did that," he says, wonder in his voice. Today, Dawkins divides his time between writing and campaigning, fighting what he feels is an essential battle. The Greatest Show on Earth is simply the latest weapon in his armoury. So finally I have to ask him, does he honestly think any creationists will read it?

"Hardline, mind-made-up creationists, no. But there are lots of people, people who think they are creationists but who haven't thought about it very hard, people who grew up in some religion or other, who are just beginning to question what they were taught. And all of a sudden they are reading about evolution and saying, wait a minute, this makes sense. I get a lot of letters from people thanking me, saying, 'You've changed my life.' That is very, very gratifying." So you have actually converted people? "Well, for example, I was at one point teaching in Oxford, and we had an animal-behaviour student who was a creationist from some out-of-the-way Bible college in America. He came dutifully to all my lectures, every week, and after the last lecture, he came down to the desk where I was packing up my notes and he said, 'Gee, this evolution, it really makes sense!' So yes, yes, I do believe that people can change their minds, be convinced by the truth. And I thought, yes, that's what I'm here for."

Emma Townshend's new book, 'Darwin's Dogs: How Darwin's Pets Helped Form a World-Changing Theory of Evolution', is published by Frances Lincoln on 5 November

The extract

The Greatest Show on Earth, By Richard Dawkins (Transworld £20)

'...Imagine you are a teacher of recent history, and your lessons on 20th-century Europe are boycotted... by politically muscular groups of Holocaust deniers. The plight of many science teachers today is not less dire. When they attempt to expound the central principle of biology they are harried and stymied, hassled and bullied'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments