Read 'em and weep: The literary masters of misery who delight in desolation

Tomorrow is officially the most dispiriting day of the year, but don't even think about fighting it, says James Kidd: it's far more rewarding to embrace the gloom in the company of a masterpiece of misery

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.April may be the cruellest month, but January is surely the bleakest: holidays over, weather miserable and those New Year resolutions already wavering. No wonder 25 January has been judged "Blue Monday" – the most depressing day of the year.

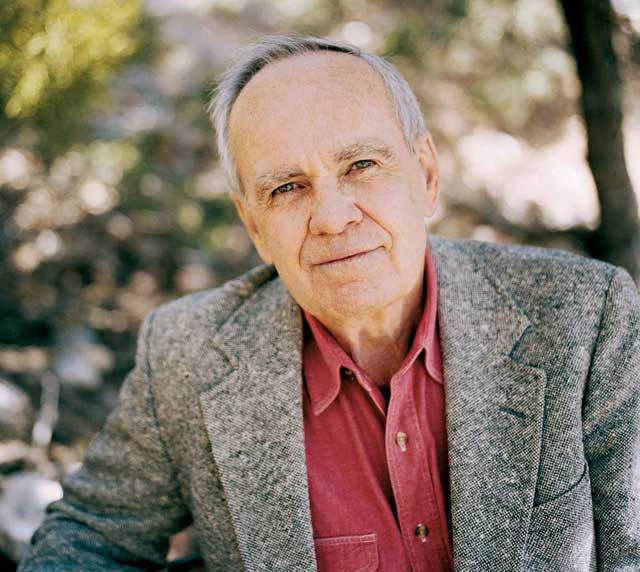

On the brighter side, though, there has never been a more appropriate moment to explore the darkest corners of your bookshelves and wallow in some truly miserable literature to enhance those winter blues. Nor is there a better starting point than Cormac McCarthy's The Road. Not even John Hillcoat's recently released film adaptation can prepare you for the slow freezer-burn of McCarthy's original.

In a shade over 300 pages, he conjures environmental desolation and physical deprivation and human degradation, not to mention the most poignant father-son relationship committed to paper. It is all narrated in the most spare and beautiful prose imaginable, which resounds with echoes of Milton, Beckett, Yeats and the Bible, yet is also entirely McCarthy's own: "Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before. Like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world."

First published in 2006, The Road has taken only three years to become a bona fide contender for the title of Saddest Novel Ever Written. It is already a fixture on the lists of misery fiction that litter book pages and the internet, vying with classic tear-jerkers and nerve-shredders such as Anna Karenina, Of Mice and Men, A Tale of Two Cities, All Quiet on the Western Front and just about any sentence by Samuel Beckett: "Ah if only this voice could stop, this meaningless voice which prevents you from being nothing, just barely prevents you from being nothing and nowhere..."

The Road's ubiquity alongside these enduring gloom-narratives pays testament to the sheer virtuosity of McCarthy's literary melancholia. True, there are heady moments when our protagonists find shelter from the storm, but the respite is always fleeting, and only intensifies the many shades of darkness that remain: the horror-show of the figures in the basement of the deserted mansion; the landscape blasted by who knows what; and the existential depiction of man's struggle to survive in an uncaring world.

What gives the story its heart and its heart-break are the characters of "Papa" and "the boy", who bicker and reconcile, despair and console, all the while trying to survive with their humanity intact: "I dont care, the boy said sobbing, I dont care.

"The man stopped. He stopped and squatted and held him. I'm sorry, he said. Dont say that. You musnt say that."

The pathos only increases when one reads the story in terms of McCarthy's own life. McCarthy dedicated The Road to his young son, John Francis, whom he fathered well into his sixties. Is the book a "Papa's" legacy to a son he probably won't live to see grow up, combined with a cri de coeur about the world that will be left him? How much more poignant are the whole-hearted exchanges of the final pages, which fuse resignation, grief and a glimmer of hope: "You have my whole heart," the "Papa" says. "You always did. You're the best guy... If I'm not here you can still talk to me. You can talk to me and I'll talk to you."

For many, The Road was the defining book of the Noughties, a decade that witnessed the resurgence of global terrorism, the decline of economic security and the ever-increasing threat of environmental collapse. Some writers exploited this sense of impending doom by looking inward (see the rise of the misery memoir). Others tried to evade it through fantasy, magic and handsome vampires. Still

others, however, confronted the fear head-on, producing tear-jerkers that fuse the best of genre fiction with a literary sensibility: Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go, Alice Sebold's The Lovely Bones, Lionel Shriver's We Need to Talk About Kevin, William Trevor's The Story of Lucy Gault and David Nicholls' One Day. Even Ian McEwan's On Chesil Beach had most readers blubbing by the end.

Perhaps McCarthy's true comrade in début de siècle sadness, however, is Annie Proulx, who does for Wyoming what McCarthy has done for Texas: 1999's Brokeback Mountain was a yearning tale of cowboy meets cowboy, cowboy loses cowboy, that ends with Ennis Del Mar's tight-lipped expression of stoic nihilism: "There was some open space between what he knew and what he tried to believe, but nothing could be done about it, and if you can't fix it you've got to stand it."

Proulx crowned her most recent collection, Fine Just the Way It Is, with a comparable blast of pessimism: "Tits Up in a Ditch" features an unhappy childhood, casualties from Iraq and a final passage that makes Del Mar sound like Jilly Cooper: "Already grief was settling around the tense couple like a rope loop... [Dakotah] had to draw the Hickses's rope tight and snub them up to the pain until they went numb, show that it didn't pay to love."

The Road's melancholy vision crawls out from older novelistic traditions than these – not least McCarthy's own Blood Meridian and No Country for Old Men, which themselves drew on Faulkner, Hemingway, Melville, Dostoevsky. Of course, if you want a portrait of love fighting for its life against a forbidding environment, you could do worse than Thomas Hardy, that master of bad things happening to good people. If Tess of the D'Urbervilles isn't strong enough, you could always try Jude the Obscure, with its taboo-breaking combination of infanticide and infant suicide.

But perhaps the most piercing of all anthems to doomed love is The End of the Affair, Graham Greene's "record of hate", which begins, aptly enough, on a dreary January day: "It was as though our love were a small creature caught in a trap and bleeding to death: I had to shut my eyes and wring its neck."

George Orwell's 1984 strikes a similar note, evoking a dystopian vision of society that destroys any hope of love, life and liberty the moment they spring up. Or how about Animal Farm, for the pathos of Boxer's "disappearance" and blunt prose such as: "Muriel was dead; Bluebell, Jessie and Pincher were dead. Jones too was dead – he had died in an inebriates' home in another part of the country."

Further chilling visions of man's inhumanity to man occur in William Golding's Lord of the Flies, Susan Hill's I'm the King of the Castle, JG Ballard's High Rise, Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart and JM Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians. Hubert Selby Jr's work is so bleakly disturbing that he claimed he couldn't stomach his own 1971 novel The Room.

If it's an apocalypse you want, Nevil Shute's On the Beach will have you diving for cover. Narrated with the stiffest of upper lips, Shute's sangfroid intensifies the pathos of this story about lives and loves cut short by a fast-spreading radiation cloud. "'I've had a lovely time since we got married,' says Mary Holmes to her husband as they prepare for the end of the world. 'Thank you for everything, Peter.'"

If you need pictures to illustrate your vision of mutually assured destruction, Raymond Briggs' When the Wind Blows might be your cup of tea. Like Shute, Briggs contrasts the minutiae of Jim and Hilda Blogg's lives with the vastness of their impending doom. What brings tears to the eyes is their struggle to comprehend the dangers they face and their misplaced trust in the powers that be.

Briggs' other masterpiece, The Snowman, provides a companion piece about joy's fleeting nature. It is also a reminder of the pure emotional power exerted by the best children's literature – see also Charlotte's Web, Tarka the Otter, Old Yeller, Watership Down and the fairy tales of Oscar Wilde.

The list could go on and on to include Jean Rhys and Edith Wharton, Heart of Darkness and Jacob's Room, Tender is the Night and Farewell to Arms, Camus and Sartre, Flaubert and Goethe, Tolstoy and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Elie Wiesel's Night and Primo Levi's If This is a Man, Chekov and Ibsen...

Of course, if you are simply too busy to wade through all this literary sadness, there is always terse, old Ernest Hemingway, who believed the world's saddest story was only six words long: "For sale: baby shoes, never used." Have a happy Blue Monday.

The extract

The Road, By Cormac McCarthy (Picador £7.99)

'...No lists of things to be done. The day providential to itself. The hour. There is no later. This is later. All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one's heart have a common provenance in pain. Their birth in grief and ashes. So, he whispered to the sleeping boy, I have you'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments