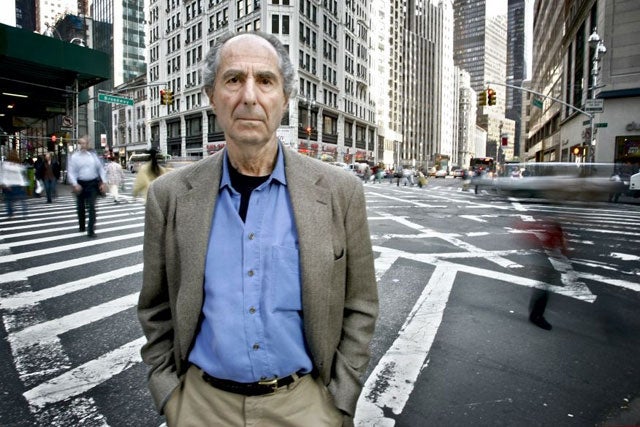

Philip Roth: America the dutiful

After his tales of death, Philip Roth recaptures youth with a novel on sex-free student life in the 1950s. John Freeman meets him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Philip Roth may have roared on to the American literary scene on the back of the sexual revolution, but all the exuberant carnality depicted in his early novels – from Alexander Portnoy's copulating with a piece of liver to the transformation of David Kepesh into an enormous, human-sized breast – proceeded from the mind of a man educated in a university setting which is, by today's standards, monkish in the extreme. Back in the early 1950s, when Roth was a college student, female students had to return to their dorms not long after sundown. Men were not allowed in their rooms. Dances were chaperoned. "That little world was replicated on one campus after another," says Roth, sitting in the office of his New York literary agent, dressed in khakis and a check shirt, not far off the preppy style of that era. "This will come as a great shock to young people, but in 1951 you could make it through college unscathed by oral sex."

These days are on Roth's mind again because they are the topic of his 29th book, Indignation (Jonathan Cape, £16.99): a short novel set in 1951 about a young Jewish man named Marcus Messner, who flees the oppressive anxieties of his family in Newark. His bolt-hole is a small, conservative liberal arts college in Ohio called Winesburg, a tick down from the Ivy League. Marcus should feel liberated, but his life becomes even more complicated when he trades the illogic of his parents' surveillance for that of the college administration.

"He goes from one overseer to another," Roth says. Marcus bristles at it. He clashes with one roommate after the next, rages at the starchy Christianity of compulsory chapel, and manages to turn his one blessing – a date with a woman who is far more sexually advanced than her times – into a source of towering anxiety.

Roth has famously mined every period of his life for fictional purposes, but this was one that had remained untouched – at least in fiction. "I never set a book in that period of the old norms, the old moral norms," he says. Having been on the front lines of these changes might have had something to do with Roth's slow boomerang back to the period. Beginning in 1956, he spent several decades on and off various university faculties. "It's still somewhat incredible to me," he says, "truly, that young men and young women sleep in the same dormitory. When I was teaching at Bard 10 years ago I saw them going in an out of the dormitory together and I was shocked. The old system was just discarded: sexual freedom, personal freedom, all the freedoms that have been extended to the generations after mine are extraordinary."

Legs crossed, his tone professorial, dipping frequently into laughter, Roth is acting less as a literary Gulliver, but rather a man who has watched his times change far beyond his own wild expectations. "I was talking to a younger generation saying, this is the way it used to be," he says about Indignation. It is not as if Roth has completely shut off from the present, though; in conversation he expresses dismay over the Republican resurgence in the presidential race, Sarah Palin's attempts to ban books from Alaskan libraries.

But the documentary storytelling impulse in Indignation is a continuation of a growing vein of Roth's work: books obsessed and possessed by American history, such as American Pastoral, I Married a Communist and The Plot Against America. At 75, with three recent fictional meditations on death behind him, Roth appears to have wrestled mortality as a concept to the side for the purpose of remembering America as it was.

One of the key freedoms Marcus lacks – which many of America's college students hardly consider today – is the freedom from fighting. In 1951, the US was at war with North Korea and the draft was on. Marcus's fear of being booted out of campus, called up, sent over and dying on the battlefield provides the book with a taut wind-up – even though Marcus essentially narrates the book from beyond the grave, after this very sequence of events occurs.

It is a state of limbo not unlike that of every soldier from that era, minus, of course, the permanence. "With the draft, everybody was involved," Roth says, "Everybody was fodder. When you got to be 21, 22 and graduated from college, for two years your life stopped. If you had been running in the direction of your life, you had to stop and do this other thing which was, if not menacing, just plain boring."

Roth experienced the boring part. Like Marcus, he spent a year in Newark at a state college before transferring in 1951 to a private liberal arts school, in his case Bucknell in western Pennsylvania. Several details about the college – the social conservatism, the partying – Roth grafts on to Winesburg. When he was at Bucknell, there was a Reserve Office Training Corps (ROTC) and, Marcus-like, he decided to protest against it. "I opted out. I was stupid, I should have stayed in. But I was against the military on the camps – a political principle which screwed me up. Then I was drafted into the army as a private. Had I stayed in ROTC, I would have been an officer. The war was over, though, so it didn't make much difference."

Several stories in Roth's first book, Goodbye, Columbus, emerged from that period – which Roth has returned to in another way. This is his fourth short work in nearly as many years. "I have a feel for this length," he says. "Goodbye, Columbus is this length." Roth also had a good teacher: Saul Bellow. "I remember that Saul, at the end of his life, was writing short novels. One was The Actual; another The Bellarosa Connection. I talked to him about that when he was doing it. I remember being fascinated that he who loved the density and complexity of novels, the spinning out of the narrative in all directions, had found this way of condensing."

Roth moved away from this form in the big, sprawling 1962 novel, Letting Go, which reveals the influence of Bellow's early novels. "I always wanted to amplify, which is what you do in a novel. Right off, when I wrote Letting Go, I found the pleasure in amplification, and building, making building blocks, big chunks of prose, making chapters. I like the feel of the weight of it."

Bellow has been dead three years now, and Roth feels the loss, personally and artistically, in a profound way. "There is no longer anybody to look up to. It's just us now. There are some very, very gifted writers in my generation: Doctorow, Don DeLillo, all of us within three or four years of each other. Don is a few years younger, Ed [Doctorow] a few years older. John Updike and I are about the same age. Joyce Carol Oates is about the same age. So is Reynolds Price."

All of these writers grew up in an era when the novel, at least in America, was given far more cultural space. "There was never a golden age, mind you," Roth says. But Updike, Roth and Oates all appeared on the covers of Time or Newsweek, something only Junot Diaz, the most recent Pulitzer winner, can claim, and this because of a special issue on the "browning of America".

The artistic frames of reference these writers once shared with a culture have also shifted. The college in Indignation is named after the novel by Sherwood Anderson which Roth complains has all but been forgotten.

So, too, has one of his teenage literary idols: Thomas Wolfe. "There wasn't a budding young literary kid of 16 or 17 who didn't fall madly in love with Thomas Wolfe," he says: "the gush of it, the torrent of feeling, and then the marvellous portraiture: the overabundance. He is by no means the genius that Bellow was, but he had a similar kind of feeling for bigness, for portraiture, for American types."

Lacking his elders, all too keenly aware his time is running short, Roth has pulled back on his reading. "I don't read much contemporary fiction," he says. "I don't read much fiction at all, just the fiction of writers I've read long ago that I'm trying to come back to one last time."

When he was writing Everyman, he was reading the short novels of Turgenev. Now he has gone back to Albert Camus, re-reading The Plague. He also recently discovered the writer's notebooks. "Whenever he goes to visit a country, the travel writing is extraordinary. He takes a trip to Greece and the writing is extraordinary. When the sun shown on a country, he saw what the light there was like."

Roth has also saved up a few last assignments for himself. "I think I'm going to re-read Moby Dick," he said, visibly excited at the thought. "It's absurd that I haven't read it since college. It's as though I never read it." About writing he is jovially evasive. In the last decade Roth has published eight books, a staggering rate for a man aged between 65 and 75. Perhaps he is ready to rest.

"I want to have a big long project that will occupy me until my death," Roth says, his big eyes shining, his expression so deadpan it may or may not be ironic. It's hard to tell. "I'm ready for it. I have a 25-year book. And when I'm one hundred I will hand it in and then lie down in darkness."

Philip Roth

Philip Roth was born in Newark, New Jersey in 1933, the second child of Jewish immigrants. He went to school in the Weequahic neighbourhood, then studied at Bucknell University and the University of Chicago. He taught writing and literature until retirement in 1991. Goodbye, Columbus (1959) won the National Book Award; he has won that honour and the PEN-Faulkner award three times, and the Pulitzer Prize once. In 1969, Portnoy's Complaint saw him hailed as a Great American Novelist but also decried. His 29 books include American Pastoral (1997), The Human Stain (2000), The Plot Against America (2004) and now Indignation (Cape).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments