Patrick Bateman and me: John Walsh comes clean about his intimate relationship with American Psycho's serial killer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the summer of 1991, I was rattling along underneath London, somewhere on the District or Circle Line. The carriage was crowded and I stood, clutching the overhead support with one hand while holding my paperback open with the other. Then it happened.

"Excuse me," said a voice from below, about level with my waist. "EXCUSE ME..."

I looked down. A woman in a red coat and matching beret was glaring up at me.

"Would you mind TELLING me," she said, in a voice that suggested she was speaking for the whole carriage, "why you're reading THAT BOOK?"

"Why do you want to know?" I asked, quelling a desire to say it was none of her damn business.

"You know why I'm asking," she said in a steely tone. "That book is notoriously nasty, disgusting and ANTI-WOMEN. There have been articles about in the papers. I want to know why anyone – why any man – would want to buy and read it." She nodded, as if congratulating herself on nailing a furtive misogynist on the Tube.

"It's by Bret Easton Ellis," I said. "A good American author. Anything he writes is worth reading, though it may not be to your taste. And I think you'll find that the killer in this book doesn't stop at women. He kills men, dogs, cats..."

"And that's to your TASTE is it?" she said contemptuously. "You must be so PROUD of yourself." With that she rose and strode off the train, leaving me under a fire of accusing looks. As if, by reading the book, I was as bad as its deranged protagonist. As if I were Patrick Bateman.

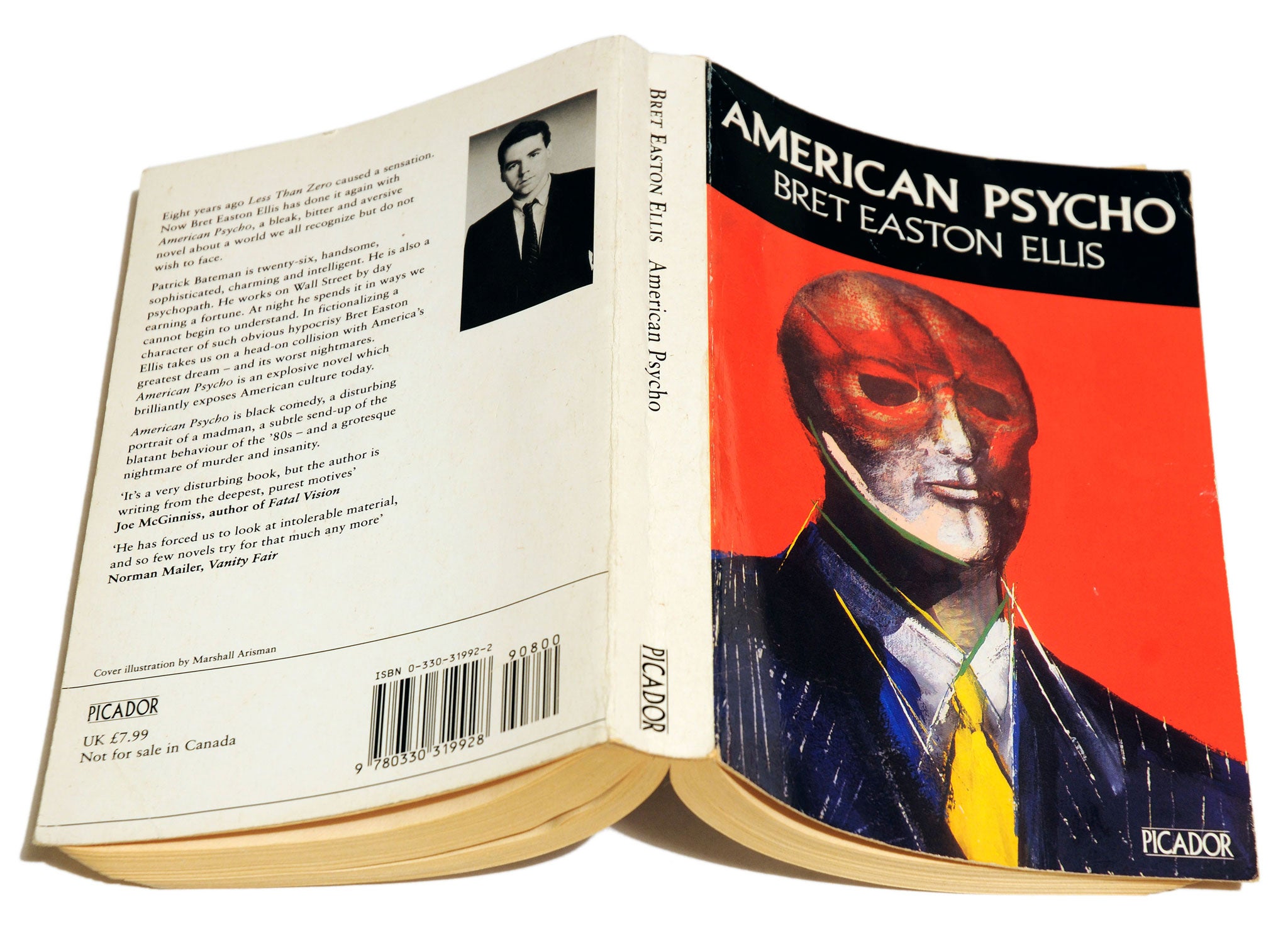

American Psycho was the succès de scandale of 1991. It caused a furore before it was published – even before it was printed. When Ellis's publishers, Simon & Schuster, sent the manuscript to their printers, one of the machinists read a paragraph and drew it to the attention of others. The printers refused to have anything to do with it – and some offending passages were leaked to the press by "concerned employees" of Simon & Schuster. The company cancelled publication, citing "aesthetic objections", but paid Ellis the full $300,000 advance anyway.

Then Spy magazine published an article abusing Ellis for one of the book's more lurid scenes involving the flaying of a woman's skin. The LA branch of the National Organisation of Women issued a statement of disgust, calling American Psycho "a how-to novel on the torture and dismemberment of women" and threatening to boycott any publisher who touched it.

For five days it seemed the book had been stifled. Then Sonny Mehta, the legendary president and editor-in-chief of Knopf bought the rights for his Vintage imprint. The book, he said, was a "serious" work of fiction. In summer 1991, American Psycho was published and loosed on the marketplace.

The reaction was outrage. Three weeks before publication, The New York Times ran a review under the headline, 'Snuff this book: don't let Bret Easton Ellis get away with murder'. Other US reviews were unanimously terrible, with the sole exception of Vanity Fair, in which Norman Mailer called it "Dostoevskian".

The response in the UK was little better. Joan Smith in The Guardian called it "an entirely negligible piece of work, badly written and wholly lacking in insight and illumination". In The Observer, Andrew Motion practically spat with fury. The book, he said, was "throughout numbingly boring and for much of the time deeply and extremely disgusting. Not interesting-disgusting but disgusting-disgusting: sickening, cheaply sensationalist, pointless except as a way of earning its author some money and notoriety."

Only two British reviewers praised Ellis's book. One was the novelist Fay Weldon, who called it a "beautifully controlled, important novel". The other was your humble scribe. Writing in The Sunday Times, where I was then literary editor, I described it as "serious, clever and shatteringly effective... For its savagely coherent picture of a society lethally addicted to blandness, it should be judged by the highest standards."

I meant it. It's an amazing satire on capitalist extremism, a world of surfaces in which everything about the milieu of bankers, bond dealers and billionaires in late-1980s Wall Street is minutely described, except the reason why one of them is killing people. Our guide is Patrick Bateman, aged 26, handsome, charming, cool, sophisticated, cynical and designer-suited. Bateman knows his labels. His eyes study the bodies and clothes of all his associates, identifying where everything comes from:

"Reed Thompson walks in wearing a wool-plaid four-button double-breasted suit and a striped cotton shirt and a silk tie, all Armani, plus slightly tacky blue cotton socks by Interwoven and black Ferragamo cap-toe shoes that look exactly like mine, with a copy of The Wall Street Journal held in a nicely manicured fist and a Bill Kaiserman tweed balmacaan overcoat draped casually across the other arm. He nods and sits across from us at the table. Soon after, Todd Broderick walks in wearing..."

Bateman's narrating voice is a seamless hybrid of nullity and irritation. He notes everything around him with toneless exactitude (until the reader starts to skim the mantra of Brooks Brothers shirts and Oliver Peoples eyewear) and passes judgement on his fellow bankers and their girlfriends with flat disgust. We eavesdrop on their conversation. Nobody talks about money, investments, or jobs; they talk about getting concert tickets, getting the best table at Dorsia or Nell's.

Four characters have a tense exchange about which has the best business card. Everyone seems interchangeable. Investment bankers called Robert or Craig or Timothy are routinely mistaken for > each other. Everyone goes to the same gym, follows the same moisturiser regimen, drinks in the same bars, fancies the same blonde "hardbody" girls. The only thing missing is any human feeling.

Bateman knows this. He accepts his own nullity. "There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me," he says at one point, "only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there."

Just as we're dulled into accepting this echo-chamber of trendy nothingness, it all kicks off on page 125. Bateman teases a down-and-out lying in the garbage on 12th Street, humiliates him until he weeps, then flicks out his eyeball with a knife, stabs him in the guts and breaks his dog's legs. Then he goes for supper.

Hereafter, the narrative breaks its chronicle of affectless encounters to describe ever-more grotesque killings and mutilations. Chapters blandly titled 'Girl' describe, in dead-eyed detail, attacks with Mace and nail-guns, the appalling rat-in-the-vagina episode, Bateman's attempt to eat a victim's brains with Grey Poupon mustard. As he gets madder, and tries to confess his ghastly crimes, his fellow bankers hardly notice. Their moral compass is haywire. "Jesus, Bateman, you're a raving lunatic!" says Craig McDermott. "You can't eat at Smith & Wollensky's without ordering the hash browns!"

There's a problem here. American Psycho is a book that's admirably clever, structurally brilliant in its beady-eyed, post-modernist way (all those recitals of clothes and shoes and haircuts) and also incontrovertibly revolting in places. In parts of Australia and New Zealand, it's still available only in shrinkwrapped form, with an R-18 sticker. There are scenes you wish you could un-read. Bret Easton Ellis later said the passages were difficult to write, that he'd written them in a two-week period after finishing the rest of the book, and used "criminology textbooks to help me with some of the more graphic descriptions. They were upsetting to write, but this is what happens when you form a partnership with the person whose story you are telling together".

Maybe that's why Patrick Bateman has stayed in my head for 22 years: because his narrating voice is so belligerently satirical about the consumer world one minute, and because it's so coldly, disgustingly inhuman the next. You have to ask yourself: do I want to know the limits of the human imagination's capacity for cruelty? Would I just rather not?

I met Ellis in 1994, three years after American Psycho, when he came to London to launch a collection of stories, The Informers. He was invited on to BBC2's Late Show. I recorded a link on-camera, describing the flap caused by his notorious earlier book, then the show, after which he was interviewed in the studio next door. That evening we met at the Ritz, where the book was being launched in the Palm Court. Le tout Londres littéraire stood around drinking champagne. Formal in a dark suit, Ellis was a curiously bland, baby-faced man with a look of chronic affront, as if he'd just been mildly insulted.

"Hi," I said, "I'm John. I saw you at The Late Show studio earlier. I was introducing the segment about you, and talking about American Psycho."

"Yeah, I remember," he said. "Is that what you were talking about? I saw you through the glass, waving your arms around. I thought, 'Wow there must be some big deal to have got this guy so worked up'."

"So you didn't actually listen to what I said?" I asked coldly.

"No!" said Ellis, laughing. "Should I have?"

He turned away. I went off him a little bit at that point, truth to tell. Remembering how I'd championed him in 1991, in the teeth of the world's disapproval, I thought he might have been more polite. I moodily crushed a mushroom vol-au-vent between my teeth and wished it were the index finger of his writing hand. A tiny twitch of Patrick Bateman annoyance had entered my soul.

In 2000, the film of American Psycho was released. Many commentators had ridiculed the idea of filming such an unfilmable book (how would they do the nail-gun bits? And the rat scene?) but they reckoned without Mary Harron, the American director of I Shot Andy Warhol (and a university contemporary of mine).

She found a style of breezy sophistication and manic comedy that turned the Ninnies of Wall Street into modern-day male Stepford Wives and made the killings almost plausible as an extreme response to their blandness. Suddenly, Bateman's bloodlust seemed merely a step away from Billy Fisher machine-gunning his tiresome granny in Billy Liar, or Jim Dixon, in Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim, longing to throttle the madrigal-loving Professor Welch.

The film's credit sequence was brilliant. What looked like drops of blood falling down the screen became a raspberry coulis drizzled on a posh dessert plate. And Christian Bale, as Bateman, was wonderful – his joshing contempt for his banking peers need turn up only a notch to hit full psychopathic wrath. And there's a wrenching pathos about his final scenes, when he confesses his crimes to his lawyer and isn't believed because, he's told, "Bateman is such a boring, spineless lightweight" that he isn't capable of murder.

Bateman returned in 2005 when Ellis published Lunar Park. Though couched as a celebrity memoir, it's a meta-fiction about a character called Bret Easton Ellis whose glamorous life as a novelist (the early chapters are more-or-less autobiographical) is disturbed when he and his family move to the suburbs and he discovers he's being stalked or haunted. And the figure doing the haunting is... Patrick Bateman, who is rumoured to be responsible for murders in suburbia.

Ellis's most vivid character has clearly proven hard to shake off. Last year, Ellis said he was planning to write a sequel to American Psycho, in which a 21st-century Bateman sets out to murder famous men including David Beckham and Gavin Rossdale, the British singer and guitarist with the band Bush. More immediately exciting, however, is the stage musical.

Since 2008, rumours have spread that two American producers, Jesse Singer and David Johnson, were looking to turn American Psycho into a musical. It's not as mad as it sounds. Sweeney Todd, the demon barber of Fleet Street, who slit the throats of his customers and sold their reconstituted flesh in his partner's pies, got the full Stephen Sondheim treatment. American Psycho will have its world premiere at London's Almeida Theatre on 3 December.

Matt Smith, the former Doctor Who, will star as Bateman. Music and lyrics are by Duncan Sheik, an American Buddhist singer-songwriter best known for the musical Spring Awakening.

At the helm is Rupert Goold, the Almeida's new boss, whose major credits are for directing Patrick Stewart in Macbeth, and the banking-crash play Enron, both at Chichester. He won Best Director at the Evening Standard Theatre Awards for both of them, in 2007 and 2009.

And what is American Psycho, and its irrepressible titular hero, Bateman, but a masterly conflation of a chimerical and superficial Enron world of dodgy money, and a man who takes to murder because he has lost sight of all sense of himself?

Sidenotes

Patrick Bateman has a tiny cameo in Ellis's 1998 novel 'Glamorama'. The book's protagonist meets him in a bar and notices a strange stain on Bateman's cuff

'Bright Lights, Big City', by Ellis's Eighties counterpart Jay McInerney, has also had the theatrical treatment. The rock musical, about a hard-partying young New Yorker, had a brief 2010 run in London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments