Nudge, nudge... Pat Kane's big ideas for busy readers

A new smart self-help book is shaping political debate. Pat Kane on the rise of big ideas for busy readers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

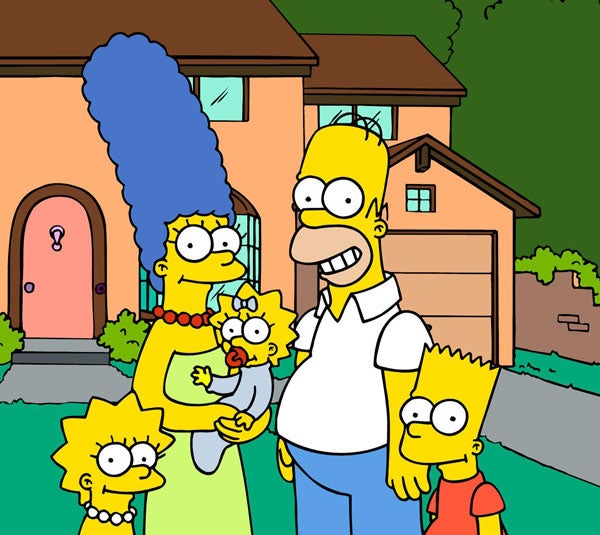

Your support makes all the difference.Across the squeaky-floored corridors of British politics and power, huddled groups of advisers are muttering one question to themselves. A question that, if correctly answered, will generate a raft of policies that might win or lose a government: "What would Homer do?" This isn't some bunch of Classics-trained wonder-wonks drawing elegant allusions from dead Greeks. They mean Homer Simpson: the cartoon everyman has become the bulbous figure stalking the political calculations of both major parties, but particularly David Cameron's Conservatives. Backed up a clutch of Nobel Prize-winners, and a coterie of academic chancers, the current "big idea" of the policy world would stretch easily across Homer's T-shirt. In short, it's this: people are dumber than they think they are.

In essence, this is the argument of Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein's Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness (Yale, £18). Regularly cited as members of Barack Obama's kitchen cabinet, Thaler and Sunstein have found their ideas circulating among the Cameronistas as well. In a speech at the Eden Project, David Cameron explicitly harnessed this work to that most familiar of conservative axioms: go with the grain of human nature. "Policy-making must always take into account how people actually behave," he said, "not how an artificial system would like them to".

One of those actual behaviours is our tendency to go with the herd. Or as Homer might not put it, to fall in with "social norms". That means "recognising that one of the most important influences on people's behaviour is what other people do," Cameron continued. "With the right prompting" – Sunstein and Thaler's "nudge" – "we'll change our behaviour to fit in with what we see around us".

Cameron gave an explicit example of what a Tory nudge to good behaviour would be: energy efficiency. If you made each house's energy use visible to every other house in a neighbourhood, you would "transform their behaviour". In Nudge, Thaler and Sunstein suggest we use an Orb, connected to our wiring, that glows green when we're doing well, and red when we're not. So Homer will go eco when he's socially embarrassed (or socially aspires) to do so. Government could pass a law that seems like a mere act of public information, but ends up getting a better result – better than some heavy-handed penalty system imposed by some Clunking Fist (guess who?).

If you think this sounds like the principle of Neighbourhood Watch taken to new extremes of suburban oppression, then you would shudder at the academic term Thaler and Sunstein give to their approach. They call it "liberal paternalism". It's paternalist to the extent that they encourage governments to create policies that nudge our forked human nature in the right direction – based on their research claims about how we don't always act in our best interests. And it's liberal in that a nudge allows you to ignore its injunctions.

So in his commitment to holding up the national obesity rate, Homer can go right on eating as many chilli fries as he likes. But if he's walking through malls where fresh fruit is prominently stacked and promoted, and the crowds around him are munching happily, he might begin to pause before stuffing his face. In one especially apposite example, Homer (like most men) finds it difficult to pee straight in the urinals. But his splash-rate will improve if he finds himself in the loos of Schiphol airport. There, a fly has been printed on the porcelain – a target, or behavioural nudge, that improves the penile aim by up to 80 per cent. At this point one wonders whether a "liberal maternalism" would be different.

Nudge is the latest in a lengthy recent line of what could be called "intellectual self-help" books. This isn't to say that self-help books don't have any theories (usually a rich stew of psychology and spirituality). But the selves that the intellectual versions are helping are, as it were, public rather than private. Books like Nicholas Taleb's The Black Swan, Malcolm Gladwell's The Tipping Point and Blink, Gerd Gigerenzer's Gut Feelings, or in the UK Richard Layard's Happiness and Charles Leadbeater's We-Think, are making the same basic proposal. How can I make sense of my personal behaviour as I face the crisis of work, the shocks of globalisation, the pervasiveness of technology, the distractions of consumerism, the churnings of gender and ethnicity? All these books think they can establish a new public language that can (as that ultimate intellectual self-helper Al Gore put it) link up "who we are" with "what we do". That link perennially interests business and politics. "Economics are the method," Mrs Thatcher mused, "but the object is to change the soul."

Economics is still the method, it seems. But the horizons of its imagined soul would seem to stretch no further than the powerplants of Springfield. According to these thinkers, when faced with the furies and possibilities of the age, our default response is an obdurate doltishness. Nudge rests on what it calls "four decades of careful research by social scientists in the emerging science of choice". Careful, possibly, but not exactly uncontested. Two strains have come together to create the "behavioural economics" they espouse. One is the advance of evolutionary biology into social science – the attack on the "blank slate" notion of human nature, first by EO Wilson, then Richard Dawkins and Steven Pinker.

The claim is well-rehearsed. Our minds and emotions have been more shaped by our millions of years of existence as barely-surviving hunter-gatherers than they have been as temple-building, law-forging, artifice-making, philosophy-writing civilians. These deeply evolved traits can upset the applecart of our personal and public plans - but they can also support, as Marek Kohn and Steven Rose often remind us, the wellsprings of altruism and community-mindedness.

It's the more Simpson-like limits to human nature which the Nudge writers emphasise - our natural greed, our short-termism, our herd mentality, our laziness in the face of the status quo. The other strain is more to do with the primacy of economics as a conceptual framework in a hyper-capitalist age. Economists have finally realised that human beings aren't the hyper-rational maximisers of gain that their calculations were based on. Now we have to go along with their equally strident claims about the messy reality of human nature.

Even as you reel from the copious referencing of books like Nudge, you smell a buried intellectual rat. It's not that every research citation involves a "survey of students" - but it does seem like every other research citation. The problem is obvious: students haven't seen much of the world, haven't much wisdom or patience, haven't learned very much at all.

In the latest New Republic, the social scientist Alan Wolfe pointed out this flaw in behavioural economics – the danger of the "Big Slip". "They glide imperceptibly from a controlled and artificial experiment to breathtaking generalizations about matters that have puzzled philosophers and theologians through the ages," he wrote acidly. "It makes for entertaining reading. Alas, it tells us little about the kind of creatures we are."

Going back to the political dimension, the British continuities are striking. Some of us remember the same goulash of research being ladled out in the pre-New Labour days. The think-tank Demos (run by Blair's eventual policy guru Geoff Mulgan) was very hot on how "evolutionary psychology" might relegitimate the work ethic. But perhaps the real expediency here lies with the self-help intellectuals themselves, tainted by publishing hype and academic competition. It's the ideas-economy, stupid. Get your "talker" placed front-of-store (alongside the fresh fruit). D'oh!

Yet there's clearly a hole in the ozone layer of contemporary thinking – a need for a conception of human nature somewhat richer than our friend, Homer Economicus. I'd benchmark all future behavioural economics against The Simpsons' Lisa. You know: the activist with the saxophone.

Pat Kane is the author of 'The Play Ethic'; www.theplayethic.com

Social help: Five of the best

By Alice Jones

Freakonomics

By Steven Levitt & Stephen J. Dubner

The thinking man's beach read, Freakonomics has sold more than 3 million copies worldwide. In it, the "rogue economist" Levitt applies economic principles to unusual subjects such as crack dealers, sumo wrestlers and the Ku Klux Klan. Credited with doing the impossible – making economics sexy – the book casts its net widely as it searches for the hidden motivations behind all manner of human behaviour.

The Wisdom Of Crowds

By James Surowiecki

This 2004 statistical-economic study sets out to disprove Nietzsche's theory that "Madness is the exception in individuals but the rule in groups". And, unlikely as it may sound, it does so using the TV game-show, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? as its model. Citing the phone-a-friend and ask-the-audience options available to contestants, the New Yorker columnist posits that collective decision-making wins out every time over individual judgement calls.

The Black Swan

By Nassim Nicholas Taleb

What do 9/11 and the immense success of Google have in common? They are both, according to Taleb's theory, black swans: that is, an unpredictable event which makes an immense impact and after which we search for an explanation or narration to make it seem more predictable than it was. Imagine how different life could be if we opened our eyes to randomness. The Black Swan has been translated into 27 languages. His follow-up, Tinkering, earned Taleb a $4m advance.

Blink

By Malcolm Gladwell

Subtitled 'The Power to Think Without Thinking', Gladwell's 2005 follow-up to The Tipping Point explores human instinct and the positive effects of split-second, snap decisions based on a narrow band of past experience. He backs up his thesis with the help of examples of this "thin-slicing" from firemen making intuitive decisions which save lives to the sub-conscious perception that tall people make good leaders. Leonardo DiCaprio is set to star in a movie adaptation.

Emotional Intelligence

By Daniel P Goleman

EI is the ability to perceive, assess and manage the emotions of one's self and others and according to psychologist and New York Times science writer Goleman, it matters more than one's IQ – and is the true key to a successful life. Gordon Brown take note. Since we are not born with a fixed level of EI, Goleman offers tips on how to hone it in all areas of life, from the workplace to marriage and child-rearing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments